Up until 20 years ago, the only planets astronomers were aware of were within our Solar System. They assumed others were out there, but none had ever been detected.

Today we know of almost a thousand planets orbiting other stars. They come in a wide variety of sizes. Some are smaller than Earth, and others are more massive than Jupiter. Some are found around solitary stars, while others are located in multiple star systems. In those systems, there can be individual or even multiple planets in orbit. In fact, recent surveys suggest there are planets orbiting every single star in the Milky Way.

So, what methods do astronomers use to find these “extrasolar planets”?

The first extrasolar planet was discovered in 1991.

It was found orbiting a pulsar, a dead star that rotates rapidly, firing out bursts of radiation on an eerily precise interval. As the planets orbit the pulsar, they pull it back and forth with their gravity. This slightly changes the wavelength of the radiation bursts streaming from the exotic star. Astronomers were able to measure these changes, and calculate the orbits of multiple planets.

Radial Velocity Method

That something, was a planet.

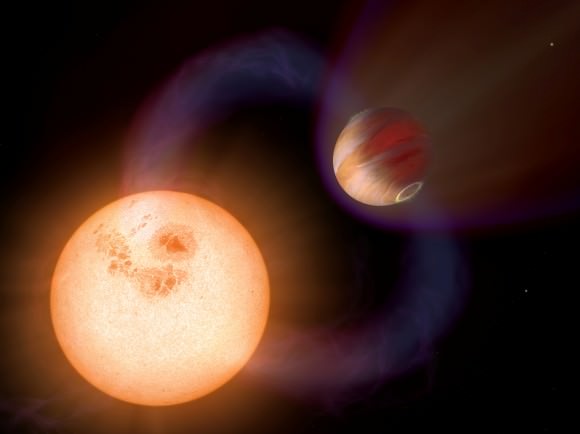

In fact, this planet was unlike anything we have in the Solar System. 51 Pegasi B has about half the mass of Jupiter and it orbits much closer to its parent star. Closer even, than Mercury to the Sun.

Until this discovery, astronomers didn’t think it was possible for planets to orbit this close, and have had to revise their theories on planetary formation. Many Hot Jupiter planets have been discovered since, some in even more extreme environments.

Gravitational Microlensing

Amateur astronomers around the world participate in microlensing studies, imaging stars quickly when an event is announced.

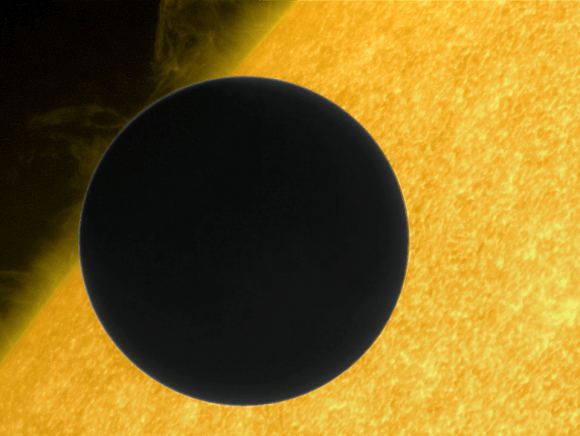

Transit Method

The most successful way of finding planets is the transit method.

This is where telescopes measure the total amount of light coming from a star, and detect a slight variation in brightness as a planet passes in front.

Using this technique, NASA’s Kepler Mission has turned up thousands of candidate planets. Including some less massive than Earth, and others in the star’s habitable zone.

From the Kepler data, It’s just a matter of time before the holy grail of planets is uncovered… an Earth-sized world, orbiting a Sun-like star within the habitable zone.

All of these techniques are limited as they require the planets to be orbiting directly between us and their star. If the planets orbit above or below this plane, we just can’t detect them.

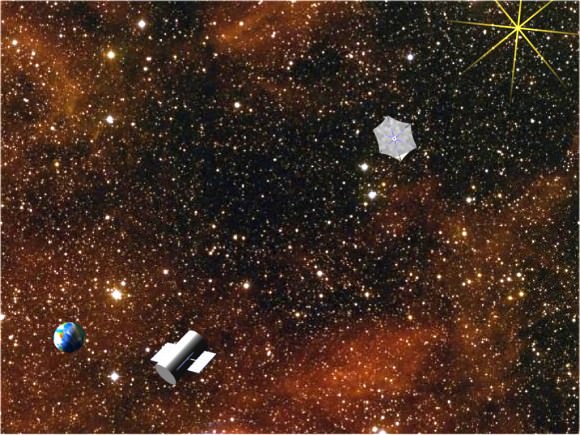

Coronographs

Imagine if you could block all the light from the star, and only see the planets in orbit. This technique has been used for observing the Sun’s atmosphere, but it requires much more precision to see distant stars.

One idea is to position a sunflower-shaped starshade in space, 125,000 km away from the observing telescope. This shade would just cover the star, dimming it by a factor of 10-billion. Light from the planets would leak around the edges.

A sophisticated instrument could even study the atmospheres of these planets, and possibly provide us with evidence of life.

We’re at an exciting time in the field of extrasolar planet research, and trust me, these clever astronomers are just getting started.

Why would the starshade be 125k km away? Can’t a smaller one be used closer in?

They find the quite fetching, thank you very much. 🙂

With regards to the Pulsar planet discovery, Fraser Cain wrote:

“It was found orbiting a pulsar, a dead star that rotates rapidly, firing

out bursts of radiation on an eerily precise interval. As the planets

orbit the pulsar, they pull it back and forth with their gravity. This

slightly changes the wavelength of the radiation bursts streaming from

the exotic star. Astronomers were able to measure these changes, and

calculate the orbits of multiple planets.”

If I’m not mistaken, the pulsar planets were not found by measuring changes in the wavelength of the radiation bursts. They were found by measuring changes TIMING of the bursts.

Indeed. Wikipedia:

“Pulsar planets are discovered through pulsar timing measurements, to detect anomalies in the pulsation period. Any bodies orbiting the pulsar will cause regular changes in its pulsation.”

Nice review! I like the historical approach since there has been a a few decades, so the first part of the article is golden.

My nitpick to add to the heap:

“From the Kepler data, It’s just a matter of time before the holy grail of planets is uncovered… an Earth-sized world, orbiting a Sun-like star within the habitable zone.”

Not if their original estimate of time needed is still applicable, ~ 7 years due to stars on average being slightly more varying than Sun. The pipeline is ~ 3.5 years worth of data. They haven’t made any new predictions that I know of.

Likely meaning we would have to be extremely lucky to see an Earth analog (Earth mass terrestrial in the habitable zone of a Sun-mass star) around a calm star.

Well done program, nicely narrated, and excellently illustrated! ( Only one recurring criticism: white-lettered – distracting – messages. )

“[R]ecent surveys suggest there are planets orbiting every single star in the Milky Way.” Further suggesting, WORLD systems attending every sun. If not now, perhaps in the past?

From perspective of one worldview, that is profoundly awesome! If THE Solar System ( battered and aged ) is a sort of template for star-planets innumerable ( many, apparency reconfigured from disordering-deterioration ), that would imply, at least one world in every time-unwinding system was meant to enclose a life-network.

But if the expansion of Time, sprang from a flash of Space, by phenomena unplanned, a “natural” event inexplicable, then, a roll of the cosmic dice: as to whether any “evolved” system, other than Earth, could have, or might yet – give birth to life.

It’s all in the numbers – a gambler’s improbable dream.