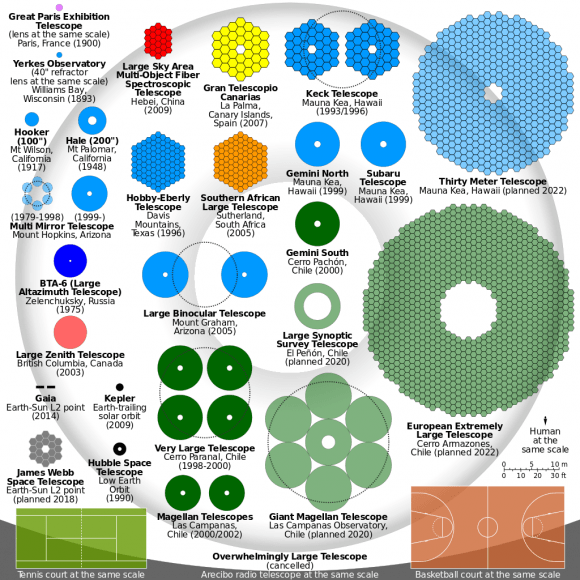

When you want to watch the sky, size really matters. The more light a telescope can collect, the more information we can get about stars, galaxies, quasars, or whatever the heck else we want to take a look at.

We’ve been fortunate in recent years to see bigger and bigger telescopes on the drawing board. Here are some of the monsters (present and future) of the astronomy world — and why their huge size really matters.

In Space

A large optical telescope we we have in orbit right now is NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope, which was launched in in 1990. It has a 2.4-meter (7.9-foot) mirror that, along with other instruments, has allowed it to refine the age of the Cosmos and show that the universe’s expansion is accelerating.

The largest current infrared space telescope is Herschel, which has a 3.5-meter (11.5-foot) primary mirror. The European observatory launched in 2009 and has racked up several achievements since making it to space. It has observed frantic star formation in galaxy clusters, spotted a molecule required for water in expiring stars like our Sun, and completed an immense cosmic dust survey.

While Hubble has helped us chart the universe’s expansion and peered deep into time, a bigger NASA telescope is on its way. Called the James Webb Space Telescope, it is expected to launch in 2018. The telescope will observe in infrared and have a 6.5-meter (21.3-foot) mirror, giving even higher resolution to our cosmic searches.

There are of course many space telescopes out there, but those are representative of some of the bigger ones. Wikipedia has a list of space observatories, but be sure to double-check the information there for authenticity.

On the ground

The largest optical reflector in the world is the Gran Telescopio Canarias in the Canary Islands, whose individual mirror segments create an equivalent light collecting surface to a 10.4-meter (34-foot) mirror. It has been used to examine comets and asteroids, exoplanets and even supernovas.

Close behind are the twin Keck telescopes at Mauna Kea in Hawaii, which each have a diameter of 10 meters (33 feet). Their discoveries include refining the Andromeda galaxy’s size and nabbing the first picture of an exoplanet system.

One method of enhancing an individual telescope’s collecting power is to pair it with others. This is something that is used, for example, with the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA), which uses 66 radio telescopes in Chile’s Atacama Desert to do observations of the universe. It’s the largest interferometer of its type in the world. It’s made some of the most distant observations of water to date.

Another example of an interferometer is the Very Large Telescope at the Paranal Observatory in Chile. It has four 8.2-meter (27-foot) mirrors and four movable 1.8 meter (5.9-foot) auxiliary telescopes. It did the first image of an extrasolar planet and also saw the afterglow of the furthest gamma-ray burst astronomers have found.

In the future

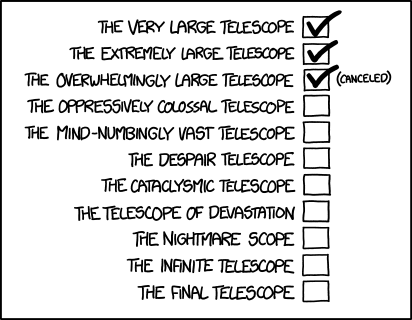

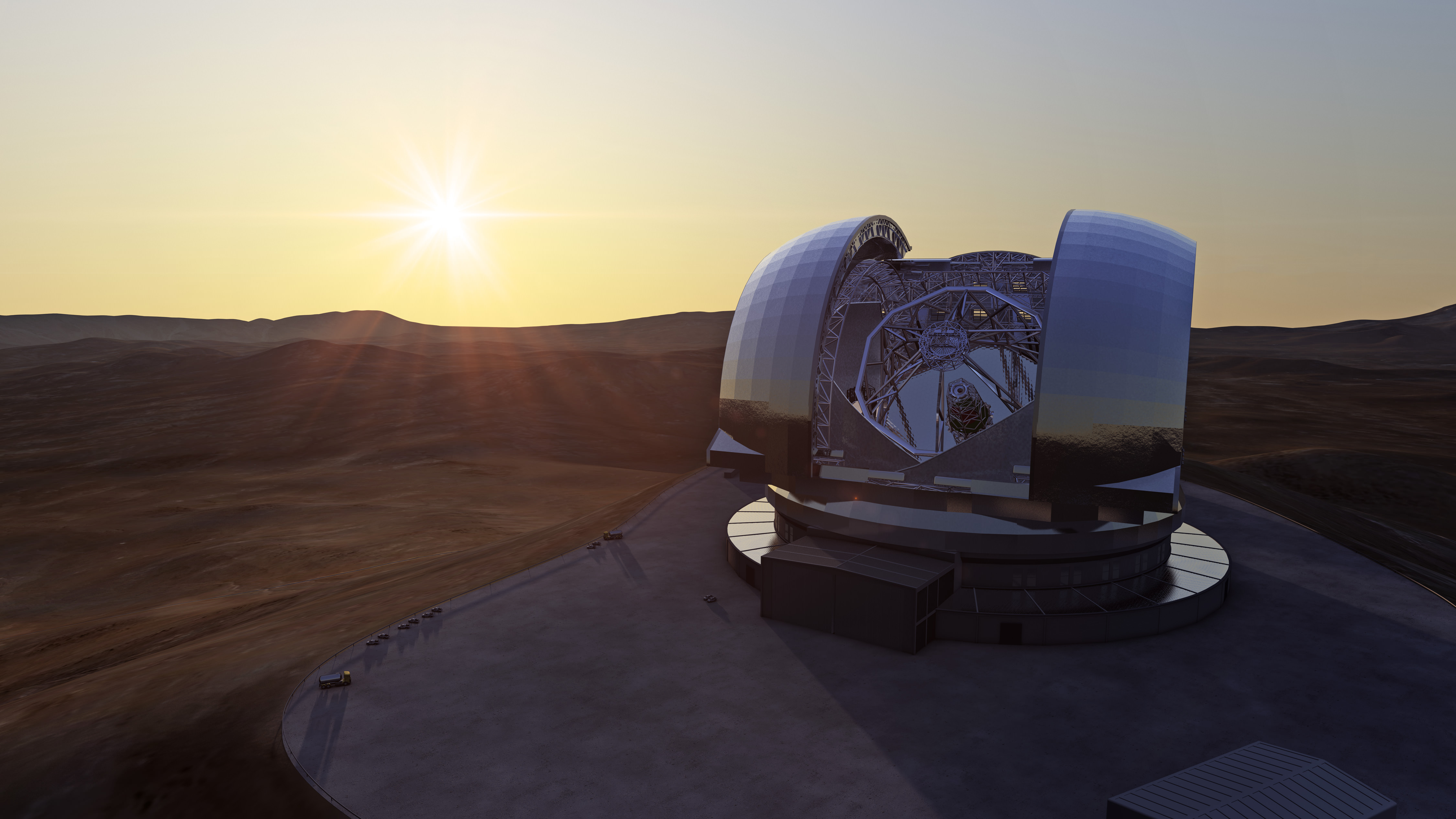

We’ve also included a small list of large telescopes yet to come. The European Extremely Large Telescope (E-ELT) at Cerro Armazones in Chile is expected to have a working mirror equivalent of nearly 40 meters (131 feet), large enough to probe exoplanet atmospheres in detail. First light date is currently set at 2024.

Also under consideration is the Thirty Meter Telescope, which would have a collecting area of 30 meters (98 feet). Construction has begun at Mauna Kea, Hawaii and first light is expected in the 2020s. Scientists may be able to use the observatory to look at giant structures in the Universe, and how planets were formed, among other things.

The Giant Magellan Telescope, set to be used at Las Campanas Observatory in Chile, will have a resolving power of 24.5 meters, or 80 feet. Commissioning is set for 2021. It will be used to probe matters such as what dark energy and dark matter are really made of, and how the Universe is expected to end.

Amazing! The superlatives being used to name these large telescopes are getting to be entertaining. What was it – 30 or 40 years during which telescope tech stagnated. Palomar was it and there was no money to build anything bigger. First it was the spin cast tech in Arizona which permitted bigger lighter mirrors. Scope mounts could be designed for something bigger than Palomar. Next material science, computer aided design and electronics for controls simplified telescope mounts and steering. Detectors better scanned the E&M spectrum and altogether lighter. Additionally, Astronomy matured into international consortiums spreading the cost among several countries. And just as James Lick wanted to leave a legacy, there have been other wealthy individuals that have lent their wealth and names to some of these massive telescopes.

It seems that the far south has been overlooked. The SALT telescope at Sutherland, South Africa has a light gathering capacity of 11 metres

Not forgotten at all. It’s the orange colored one towards the center of the graphic.

Surprised you dont show the Russian BTA 6 which was 6 m built in 1975. It didn’t work that well. A combination of poor seeing, poor construction and control but if all your after is size then it should be shown.

The WHT in La Palma at 4.2 metres, though not the largest, in the late 80’s and early 90’s through a combination of size and superior detectors was probably the best in the world until superceeded by Keck.