When there is a tsunami coming towards your home, you want to know about it as far in advance as possible. An early warning about such a disaster could save countless lives, and using Global Positioning System information may just be the way to speed up our reaction time in the future.

The traditional tsunami warning system relies on measuring the magnitude of the earthquake that causes the tsunami. This method is not always reliable, though, as calculating accurately the power of the resulting ocean waves takes hours or days.

For example, 2005 Nias quake near Indonesia was estimated to cause about the same size of tsunami as the powerful 2004 Indian Ocean quake, which destroyed cities in portions of Indonesia, India and Thailand and killed more than 225,000 people. The 2005 tsunami did not nearly meet the same proportions as the earlier quake. There have been five false tsunami alarms between 2005 and 2007, which can reduce the effectiveness of the warnings in the eye of the public.

In a study published in the December Geophysical Research Letters, researcher Y. Tony Song of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, showed that using GPS from coastal areas near the epicenter of the quake could help more accurately and quickly determine the scale of a tsunami.

Here’s how it would potentially work: data from seismometers near the earthquake’s epicenter is first registered, as in the traditional system. After that, GPS data of the seafloor displacement is factored in, which gives a more complete picture of the extent and power of the earthquake. The size of the predicted tsunami is then quickly calculated and given a number between 1 and 10 – 1 being the lowest – much like the Richter scale. This information could then be passed through the tsunami warning system to evacuate people to safety.

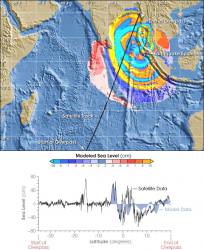

GPS data helps create a 3-dimensional model of the tsunami by giving details about the horizontal and vertical displacement of the seafloor, and this data can be sent and analyzed in minutes from coastal GPS stations. Song’s methods have accurately modeled three previous tsunamis: one in Alaska in 1964, the Indian Ocean tsunami in 2004, and the 2005 Nias tsunami.

Source: JPL Press Release

Your figure (apparently a model of the Indian Ocean Tsunami of 2004) indicates a modeled positive tsunami sea level response of between 1 and 16 metres occurring in the Gulf of Thailand from an event centred off the north west coast of Sumatra. An event of this magnitude would have had serious effects on both Bangkok and on Pattayya beach. Am I correct in assuming that the model does not take local topography into account or were there been reports of tsunami activity in that gulf that did not get public attention?

Timothy,

The picture is from this link: http://www.noaanews.noaa.gov/stories2005/s2365.htm

You are right that it’s the Indian Ocean Tsunami, but it’s two hours after the quake. If you click on the picture to enlarge it, you’ll notice that the scale is in centimeters and not meters. Thanks for your comment, and hope this helps!