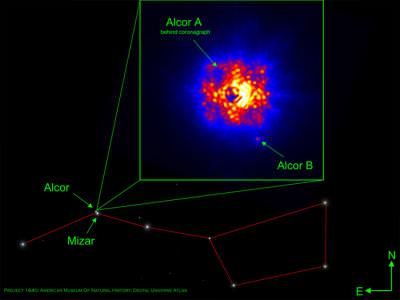

The handle of the Big Dipper just got stronger! Astronomers have found an additional star located in the Dipper’s gripper that is invisible to the unaided eye. Alcor, one of the stars that makes the bend in the Big Dipper’s handle has a smaller red dwarf companion orbiting it. Now known as “Alcor B,” the star was found with an innovative technique called “common parallactic motion,” and was found by members of Project 1640, an international collaborative team that gives a nod to the insight of Galileo Gallilei.

“We used a brand new technique for determining that an object orbits a nearby star, a technique that’s a nice nod to Galileo,” says Ben R. Oppenheimer, Curator at the Museum of Natural History. “Galileo showed tremendous foresight. Four hundred years ago, he realized that if Copernicus was right—that the Earth orbits the Sun—they could show it by observing the ‘parallactic motion’ of the nearest stars. Incredibly, Galileo tried to use Alcor to see it but didn’t have the necessary precision.”

If Galileo had been able to see change over time in Alcor’s position, he would have had conclusive evidence that Copernicus was right. Parallactic motion is the way nearby stars appear to move in an annual, repeatable pattern relative to much more distant stars, simply because the observer on Earth is circling the Sun and sees these stars from different places over the year.

The collaborative team that found the star includes astronomers from the American Museum of Natural History, the University of Cambridge’s Institute of Astronomy, the California Institute of Technology, and NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

Alcor is a relatively young star twice the mass of the Sun. Stars this massive are relatively rare, short-lived, and bright. Alcor and its cousins in the Big Dipper formed from the same cloud of matter about 500 million years ago, something unusual for a constellation since most of these patterns in the sky are composed of unrelated stars. Alcor shares a position in the Big Dipper constellation with another star, Mizar. In fact, both stars were used as a common test of eyesight—being able to distinguish “the rider from the horse”—among ancient people. One of Galileo’s colleagues observed that Mizar itself is actually a double, the first binary star system resolved by a telescope. Many years later, the two components Mizar A and B were themselves determined each to be tightly orbiting binaries, altogether forming a quadruple system.

In March, members of Project 1640 attached their coronagraph and adaptive optics to the 200-inch Hale Telescope at the Palomar Observatory in California and pointed to Alcor. “Right away I spotted a faint point of light next to the star,” says Neil Zimmerman, a graduate student at Columbia University who is doing his PhD dissertation at the Museum. “No one had reported this object before, and it was very close to Alcor, so we realized it was probably an unknown companion star.”

The team retuned a few months later and found the star had the same motion as Alcor, proving it was a companion star.

Alcor and its smaller companion Alcor B are both about 80 light-years away and orbit each other every 90 years or more. The team was also able to determine Alcor B is a common type of M-dwarf star or red dwarf that is about 250 times the mass of Jupiter, or roughly a quarter of the mass of our Sun. The companion is much smaller and cooler than Alcor A.

“Red dwarfs are not commonly reported around the brighter higher mass type of star that Alcor is, but we have a hunch that they are actually fairly common,” says Oppenheimer. “This discovery shows that even the brightest and most familiar stars in the sky hold secrets we have yet to reveal.”

The team plans to use parallactic motion again in the future. “We hope to use the same technique to check that other objects we find like exoplanets are truly bound to their host stars,” says Zimmerman. “In fact, we anticipate other research groups hunting for exoplanets will also use this technique to speed up the discovery process.”

Source: EurekAlert

Weird, the Galileo thing. The ancient Greeks knew about parallax, and used its indetectability to argue that heliocentrism is false, or, conversely that the stars are a long way away.

The actual work on parallax was done after Galileo. Flamsteed discovered proper motion, and Bradley discovered aberration, trying to detect it. Eventually Bessel managed it with 61 Cygni.

Ok, there’s an Alcor connection but it strikes me as pretty tenuous.

I wish that you Americans would call the “Big Dipper” by its proper Latin name of Ursa Major (the Great Bear).

IVAN3MAN: Well, just think of the Big Dipper as the posterior end of the Great Bear! =D

“Galileo showed tremendous foresight. Four hundred years ago, he realized that if Copernicus was right—that the Earth orbits the Sun—they could show it by observing the ‘parallactic motion’ of the nearest stars. Incredibly, Galileo tried to use Alcor to see it but didn’t have the necessary precision.”

In fact, it Galileo observed components of Mizar itself (some 15 arcseconds apart) rather than Alcor. See my article at

http://www.leosondra.cz/en/mizar/

IVAN3MAN,

I think Nancy’s reference to the Big Dipper (in paragraph 5, at least) was a nod to the Ursa Major Moving Group. According to Wikipedia, “The Ursa Major Moving Group was discovered in 1869 by Richard A. Proctor, who noticed that, except for Dubhe and Alkaid, the stars of the Big Dipper asterism all have proper motions heading towards a common point in Sagittarius. Thus, the Big Dipper, unlike most constellations or asterisms, is largely composed of related stars.”

This disintegrating nearby cluster has other members in that region of the sky but also extended members that may include Sirius (or not, see Wiki). A good overview of this loose, nearby group can be found through the SEDS site: http://seds.lpl.arizona.edu/messier/xtra/ngc/uma-cl.html .

When I hear the term Big Dipper, I think of the ‘asterism’ within Ursa Major. I think this was/is known as the Plough or Charles’ Wain in the British Isles, IIRC.

Looks more like a dipper than a bear. (Also looks more like a plough than a bear.}

How does a red dwarf end up orbited such a large bright, star? Wouldn’t both stars have been formed at near the same time?

If you do research on Ursa Major/Big Dipper etc, you will find many different civilizations throughout history had their own take on those groups of stars (Chinese saw a dragon for instance; American Indians saw something else, etc). So call it whatever you like… however, don’t display ignorance by demanding it be known as something you are familiar with. We have plenty of those individuals around here already!