Scientists recently discovered something about auroras they never knew before. “Our jaws dropped when we saw the movies for the first time,” said Larry Lyons of the University of California-Los Angeles,(UCLA) describing how sometimes, vast curtains of aurora borealis collide, producing spectacular outbursts of light. “These outbursts are telling us something very fundamental about the nature of auroras.” These collisions can be so large, that isolated observers on Earth — with limited fields of view — have never noticed them before. It took a network of sensitive cameras spread across thousands of miles to get the big picture.

[/caption]

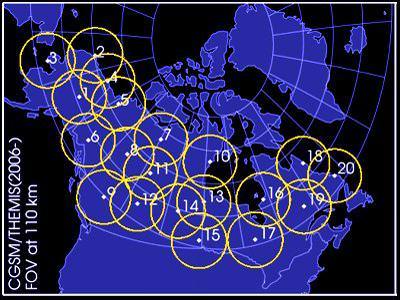

This network of 20 cameras, set up by NASA and the Canadian Space Agency was deployed around the Arctic in support of the THEMIS mission, the “Time History of Events and Macroscale Interactions during Substorms.” THEMIS consists of five identical probes launched in 2006 to solve a long-standing mystery: Why do auroras occasionally erupt in an explosion of light called a substorm?

The cameras would photograph auroras from below while the spacecraft sampled charged particles and electromagnetic fields from above. Together, the on-ground cameras and spacecraft would see the action from both sides and be able to piece together cause and effect—or so researchers hoped. It seems to have worked.

The breakthrough came earlier this year when UCLA researcher Toshi Nishimura assembled continent-wide movies from the individual ASI cameras. “It can be a little tricky,” Nishimura said. “Each camera has its own local weather and lighting conditions, and the auroras are different distances from each camera. I’ve got to account for these factors for six or more cameras simultaneously to make a coherent, large-scale movie.”

The first movie he showed Lyons was a pair of auroras crashing together in Dec. 2007. “It was like nothing I had seen before,” Lyons recalled. “Over the next several days, we surveyed more events. Our excitement mounted as we became convinced that the collisions were happening over and over.”

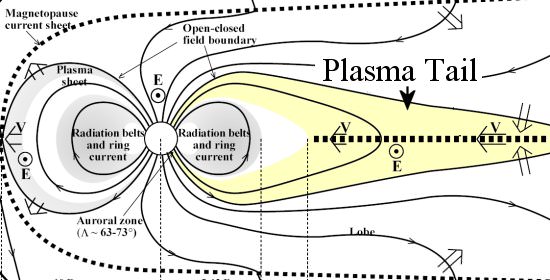

The explosions of light, they believe, are a sign of something dramatic happening in the space around Earth—specifically, in Earth’s “plasma tail.” Millions of kilometers long and pointed away from the sun, the plasma tail is made of charged particles captured mainly from the solar wind. Sometimes called the “plasma sheet,” the tail is held together by Earth’s magnetic field.

The same magnetic field that holds the tail together also connects it to Earth’s polar regions. Because of this connection, watching the dance of Northern Lights can reveal much about what’s happening in the plasma tail.

THEMIS project scientist Dave Sibeck of NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, Md. said, “By putting together data from ground-based cameras, ground-based radar, and the THEMIS spacecraft, we now have a nearly complete picture of what causes explosive auroral substorms,”

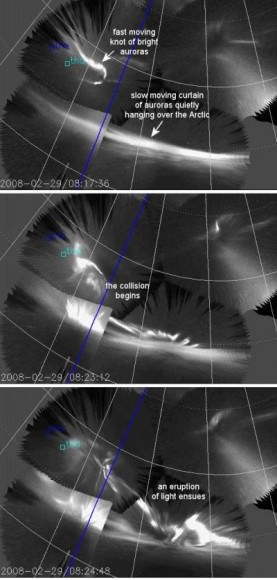

Lyons and Nishimura have identified a common sequence of events. It begins with a broad curtain of slow-moving auroras and a smaller knot of fast-moving auroras, initially far apart. The slow curtain quietly hangs in place, almost immobile, when the speedy knot rushes in from the north. The auroras collide and an eruption of light ensues.

How does this sequence connect to events in the plasma tail? Lyons believes the fast-moving knot is associated with a stream of relatively lightweight plasma jetting through the tail. The stream gets started in the outer regions of the plasma tail and moves rapidly inward toward Earth. The fast knot of auroras moves in synch with this stream.

Meanwhile, the broad curtain of auroras is connected to the stationary inner boundary of the plasma tail and fueled by plasma instabilities there. When the lightweight stream reaches the inner boundary of the plasma tail, there is an eruption of plasma waves and instabilities. This collision of plasma is mirrored by a collision of auroras over the poles.

Movies of the phenomenon were unveiled at the Fall Meeting of the American Geophysical Union today in San Francisco.

Sources: EurekAlert, Science@NASA