At the end of the proverbial day, space-based missions like Spitzer produce millions of observations of astronomical objects, phenomena, and events. And those terabytes of data are used to test hypotheses in astrophysics which lead to a deeper understanding of the universe and our home in it, and perhaps some breakthrough whose here-on-the-ground implementation leads to a major, historic improvement in human welfare and planetary ecosystem health.

But such missions also leave more immediate legacies, in terms of the pleasure they bring millions of people, via the beauty of their images (not to mention posters, computer wallpaper and screen savers, and even inspiration for avatars).

Some recent results from one of Spitzer’s programs – SAGE-SMC – are no exception.

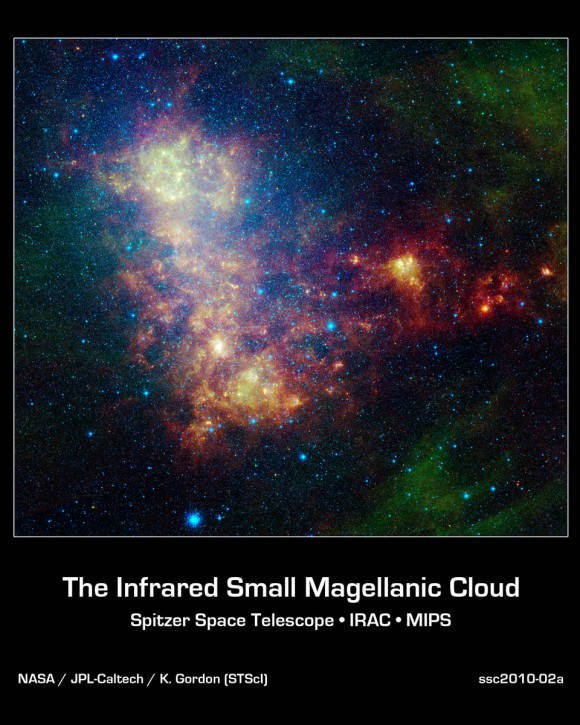

The image shows the main body of the Small Magellanic Cloud (SMC), which is comprised of the “bar” on the left and a “wing” extending to the right. The bar contains both old stars (in blue) and young stars lighting up their natal dust (green/red). The wing mainly contains young stars. In addition, the image contains a galactic globular cluster in the lower left (blue cluster of stars) and emission from dust in our own galaxy (green in the upper right and lower right corners).

The data in this image are being used by astronomers to study the lifecycle of dust in the entire galaxy: from the formation in stellar atmospheres, to the reservoir containing the present day interstellar medium, and the dust consumed in forming new stars. The dust being formed in old, evolved stars (blue stars with a red tinge) is measured using mid-infrared wavelengths. The present day interstellar dust is weighed by measuring the intensity and color of emission at longer infrared wavelengths. The rate at which the raw material is being consumed is determined by studying ionized gas regions and the younger stars (yellow/red extended regions). The SMC is one of very few galaxies where this type of study is possible, and the research could not be done without Spitzer.

This image was captured by Spitzer’s infrared array camera and multiband imaging photometer (blue is 3.6-micron light; green is 8.0 microns; and red is combination of 24-, 70- and 160-micron light). The blue color mainly traces old stars. The green color traces emission from organic dust grains (mainly polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons). The red traces emission from larger, cooler dust grains.

The image was taken as part of the Spitzer Legacy program known as SAGE-SMC: Surveying the Agents of Galaxy Evolution in the Tidally-Stripped, Low Metallicity Small Magellanic Cloud.

The Small Magellanic Cloud (SMC), and its larger sister galaxy, the Large Magellanic Cloud (LMC), are named after the seafaring explorer Ferdinand Magellan, who documented them while circling the globe nearly 500 years ago. From Earth’s southern hemisphere, they can appear as wispy clouds. The SMC is the further of the pair, at 200,000 light-years away.

Recent research has shown that the galaxies may not, as previously suspected, orbit around our galaxy, the Milky Way. Instead, they are thought to be merely sailing by, destined to go their own way. Astronomers say the two galaxies, which are both less evolved than a galaxy like ours, were triggered to create bursts of new stars by gravitational interactions with the Milky Way and with each other. In fact, the LMC may eventually consume its smaller companion.

Karl Gordon, the principal investigator of the latest Spitzer observations at the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore, Maryland, and his team are interested in the SMC not only because it is so close and compact, but also because it is very similar to young galaxies thought to populate the universe billions of years ago. The SMC has only one-fifth the amount of heavier elements, such as carbon, contained in the Milky Way, which means that its stars haven’t been around long enough to pump large amounts of these elements back into their environment. Such elements were necessary for life to form in our solar system.

Studies of the SMC therefore offer a glimpse into the different types of environments in which stars form.

“It’s quite the treasure trove,” said Gordon, “because this galaxy is so close and relatively large, we can study all the various stages and facets of how stars form in one environment.” He continued: “With Spitzer, we are pinpointing how to best calculate the numbers of new stars that are forming right now. Observations in the infrared give us a view into the birthplace of stars, unveiling the dust-enshrouded locations where stars have just formed.”

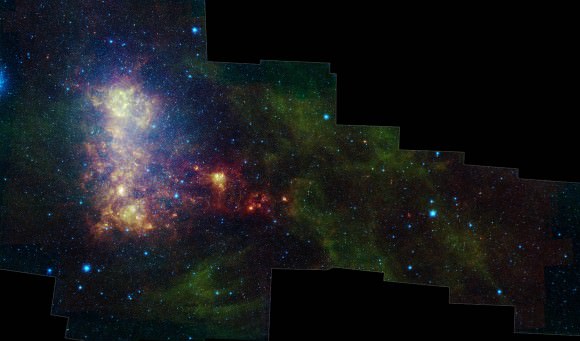

This image shows the main body of the SMC, which is comprised of the “bar” and “wing” on the left and the “tail” extending to the right. The tail contains only gas, dust and newly formed stars. Spitzer data has confirmed that the tail region was recently torn off the main body of the galaxy. Two of the tail clusters, which are still embedded in their birth clouds, can be seen as red dots.

Source: Spitzer

While strolling down the SMC “tail” in the 65Mb image, several near edge-on galaxies really stood out! The Spitzer site has two different views of the SMC tail. It’s really interesting to follow this debris trail that’s gradually merging with the Magellanic Stream and eventually accreting onto the inner halo of the Milky Way Galaxy. Future MW clusters now reside (gravitationally) in the SMC, LMC Sagittarius, Fornax & Carina Dwarf Galaxies, among others.

“The Scattered Debris of the Magellanic Stream” can be found here: http://arxiv.org/abs/0805.0820v1 .

I still think the Magellanic Streams should be studied in light of other ancient stellar streams located in the halo of the Milky Galaxy like the Sagattarius stream parts A & B as well as other putative stellar streams liker the orphan stream, etc. Future stars and clusters will secretly accrete onto the halo of the Milky Way over the next billions years, adding to the splendour of the natural wonders.