[/caption]

Juno, NASA’s next big mission bound for the outer planets, has arrived at the Kennedy Space Center to kick off the final leg of launch preparations in anticipation of blastoff for Jupiter this summer.

The huge solar-powered Juno spacecraft will skim to within 4800 kilometers (3000 miles) of the cloud tops of Jupiter to study the origin and evolution of our solar system’s largest planet. Understanding the mechanism of how Jupiter formed will lead to a better understanding of the origin of planetary systems around other stars throughout our galaxy.

Juno will be spinning like a windmill as it fly’s in a highly elliptical polar orbit and investigates the gas giant’s origins, structure, atmosphere and magnetosphere with a suite of nine science instruments.

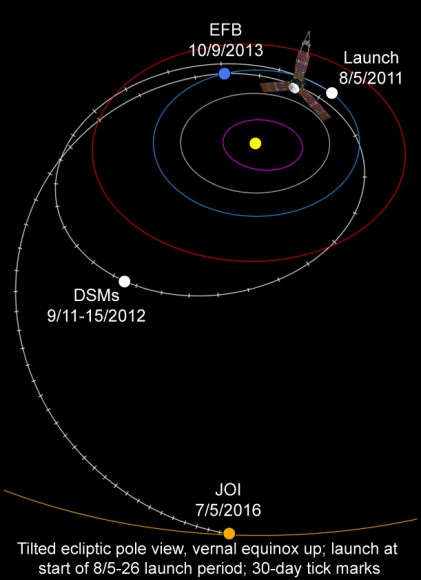

During the five year cruise to Jupiter, the 3,600 kilogram probe will fly by Earth once in 2013 to pick up speed and accelerate Juno past the asteroid belt on its long journey to the Jovian system where it arrives in July 2016.

Juno will orbit Jupiter 33 times and search for the existence of a solid planetary core, map Jupiter’s intense magnetic field, measure the amount of water and ammonia in the deep atmosphere, and observe the planet’s auroras.

The mission will provide the first detailed glimpse of Jupiter’s poles and is set to last approximately one year. The elliptical orbit will allow Juno to avoid most of Jupiter’s harsh radiation regions that can severely damage the spacecraft systems.

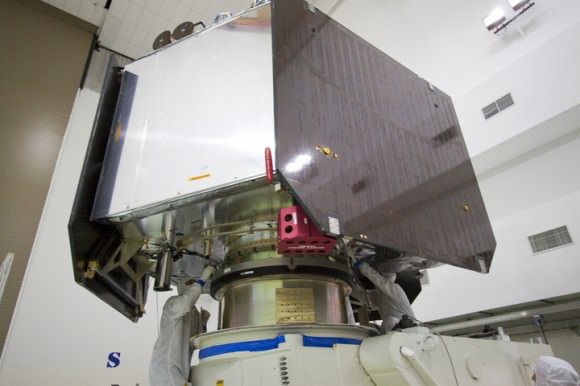

Juno was designed and built by Lockheed Martin Space Systems, Denver, and air shipped in a protective shipping container inside the belly of a U.S. Air Force C-17 Globemaster cargo jet to the Astrotech payload processing facility in Titusville, Fla.

This week the spacecraft begins about four months of final functional testing and integration inside the climate controlled clean room and undergoes a thorough verification that all its systems are healthy. Other processing work before launch includes attachment of the long magnetometer boom and solar arrays which arrived earlier.

Juno is the first solar powered probe to be launched to the outer planets and operate at such a great distance from the sun. Since Jupiter receives 25 times less sunlight than Earth, Juno will carry three giant solar panels, each spanning more than 20 meters (66 feet) in length. They will remain continuously in sunlight from the time they are unfurled after launch through the end of the mission.

“The Juno spacecraft and the team have come a long way since this project was first conceived in 2003,” said Scott Bolton, Juno’s principal investigator, based at Southwest Research Institute in San Antonio, in a statement. “We’re only a few months away from a mission of discovery that could very well rewrite the books on not only how Jupiter was born, but how our solar system came into being.”

Juno is slated to launch aboard the most powerful version of the Atlas V rocket – augmented by 5 solid rocket boosters – from Cape Canaveral, Fla. on August 5. The launch window extends through August 26. Juno is the second mission in NASA’s New Frontiers program.

NASA’s Mars Curiosity Rover will follow Juno to the Atlas launch pad, and is scheduled to liftoff in late November 2011. Read my stories about Curiosity here and here.

Because of cuts to NASA’s budget by politicians in Washington, the long hoped for mission to investigate the Jovian moon Europa may be axed, along with other high priority science missions. Europa may harbor subsurface oceans of liquid water and is a prime target in NASA’s search for life beyond Earth.

Starting with “New Horizons” arrival at Pluto on July 2015, then in the same month Dawn will reach the other dwarf planet, Ceres in the same very month! this is going to be a very exciting twelve months for the planets. Now the Juno mission one year later, Well all I can say is, bring it on!!!

Assuming we don’t get a close-up of “Niburu” next year, I too am extremely excited about the remainder of this decade and the discoveries we are yet to make. We are blessed to live in such a golden age of cosmic exploration.

‘Carl Sagan’s Roach Clip’

Best handle ever. Well played sir.

Niburu!?

“May’a suggest an int’resting year for ya’, sir?”

I agree–what an exciting year or two that will be! Hope we are alive and healthy then and have weathered the December 2012 end of the world scenario…

Technicians at Astrotech unfurl solar array No. 1 with a magnetometer boom that will help power NASA’s Juno spacecraft

This reads like the magnetometer boom does the power help. It doesn’t, does it?

I think it means that the magnetometer boom is going to unfurl the solar array. That’s how I read it anyway.

This is great!! Do they something in store for EUROPA? It must be a fascinating place to explore.

Also hope that we have something for titan up next…

There’s the EJSM (Europa Jupiter System Mission) which has a projected launch date of 2020, which potentially could carry with it a Europa lander or orbiter. As far as I’m aware, that’s been given priority over a proposed mission to Titan on roughly the same timeline.

Should note neither of these are confirmed.

There are likely some changes from recent NASA information to ESA on budget problems. (James Webb ate the money.) As a result, ESA will go alone on some of the missions below; this is from ESA’s site:

“The remaining candidate L-class missions for the L1 launch slot are:

EJSM-Laplace http://sci.esa.int/ejsm

IXO http://sci.esa.int/ixo

LISA http://sci.esa.int/lisa”

Best case scenario may be that NASA does EJSM alone; its part is Jupiter, Europe & Io studies. While ESA does one of the other two missions.

One would think that if the Mayans could predict the future they would have handled the whole Cortez thing differently.

Eh, who knows? Whenever someone comes at me with the whole 2012 world ending thing I usually reply. Oh yeah well Nostradamus said the world doesn’t end till like 5324 or something. It’s kinda like fighting fire with fire. Or manure with manure to be more accurate. Lol

Dav-Daddy. I like that reply. There are probably dozens if not hundreds of ‘end of the world’ prophesies out there to use. Isn’t there a new one that is appearing on bill (Bull??) boards about Jesus returning soon? Can’t wait to see what the believers are going to do with the T-shirts when that one comes and goes and they still have to go to work on Monday.

I cannot help but think:

What the H*LL? solar arrays 20 meters long, and three of them??

The tree huggers really got their way this time, me thinks. No RTG for this space craft?

I dare predict that this mission is going to fail, and most likely because of the failure of just one solar array. This is enough to put the centre of mass way out of the middle causing the instruments themselves to sway like mad, resulting in a total mission failure.

Solar arrays on a spacecraft like this, bad thing. me thinks. and how about you?

Slight corrections to my prediction:

I meant by solar array failure, solor array unfurling failure. Causing the centre of mass to be somewhere else that it should be. Causing all the instruments in the craft to sway due to the rotation of the spacecraft.

@ PMF71

This started out as a short answer, sorry — it got longer, there really is a lot involved with this use of RTG fuels.

The “dependable for space use” long term (talking favorable half life vs power output here) RI fuels need to be made again from the looks of the supply right now. The best choice for RTG fuel is in such short supply that I doubt NASA, JAXA, or ESA could gather enough for more than a mission apiece on the common market. There is a lot still in use by defense agencies around the world I am sure but they don’t usually sell on the common market now do they -grin-.

If luck stands ready to assist these agencies, and they find what seems to be enough pellets… these already pressed and cindered pellets are well past the best-start-use-by ‘initial usage dates’ and will give less than required time on mission while still requiring the cask weight to remain the same or be greater re the parasitic mass. For example AM-241 has only 1/4 the wattage of PU-238 but requires more shielding since many of the decay chain products are more active than PU-238.

The use of a pile to create any new supplies would be required. This requires any government to act in the face of public fears since these piles are also used for other fuels –new fuel rods and to reprocess used contaminated spent fuel rods and therein is the material for bombs. In the USA we have signed treaties stating we will not make ‘many’ of the bomb materials from the piles and this includes many fuels, these do not exclude RTG fuels, but they do not explicitly allow the generation of such fuels, many terms and clauses would need interpretive service. The making of the bomb materials is a part of the isolation of the RTG fuels as well. Additionally using the pile to knock a few protons around, add a neutron here and there to create some of the fuels creates more of the materials from which bombs can be made. A catch-22 in the making here.

Changing the ‘assembly line’ for RTG fuels at a pile would be done one item at a time for each isotope from start to finish for traceability alone, not to mention contamination problems introduced at any stage by a co-generation line from the same pile. This consumes labor and time away from ‘normal’ production, the cost is more than just that needed to create and or isolate the isotopes.

The USA and France need to start up production again I think. I do not know if Russia can still create these isotopes dependably anymore. Sad state of affairs isn’t it.

We made a lot, used a lot, and time has taken its toll on the remaining publicly available supply. Fewer than 30 atomic isotopes within the entire table of nuclides are dependable in space. Plutonium-238, curium-244 and strontium-90 are the most often cited isotopes, but other isotopes such as polonium-210, promethium-147, caesium-137, cerium-144, ruthenium-106, cobalt-60, curium-242 and thulium isotopes have also been studied in great detail to a favorable view, they can be used for long term low solar function missions or we could use more solar square area even with the inherent problems that each poses; tossing a coin I see more panels in the future.

I agree with your assessment of any potential failure in deployment of the panels causing an offset of the center of mass; they hope to use the spinning bullet system to assist in the panel deployment if memory serves me today. Maybe they planned a spiral escapement for the panels from the storage area. If they do it right there should be little holding proper deployment back or stopping the egress of the panels. If they do not do things rightly enough though… it may not work well enough to serve for the mission as planned and may not work well enough for any part of the mission, for ex. if two panels are partially detached at the hub and at one joint (a different joint on each array) the mission can live from the specs I recall but total loss of a panel’s mass for the offset of mass would be a game changer. The power requirements might be met with two and 1/3 panels but the center will not hold, as it were, ah humm, I’ll be leaving now this is long enough by too much.

Mike C

I am aware that there is a shortage in RTG fuels, but i never expected the reason to be so complicated, so thanks for that informative answer. Nor did i expect the supply of RTG fuels to be so low that it impedes deep space missions.

So the problem is in fact shortsightedness by the masses. I think that about sums it up 😉

Or maybe a lack of trust/trustworthiness is an even shorter answer.

At that, dear friend is a real damn shame.