[/caption]

While many of us here on Earth were waiting for the Moon to take a bite out of the Sun this past Sunday, Cassini was doing some moon watching of its own, 828.5 million miles away!

The image above is a color-composite raw image of Methone (pronounced meh-tho-nee), a tiny, egg-shaped moon only 2 miles (3 km) across. Discovered by Cassini in 2004, Methone’s orbit lies between Mimas and Enceladus, at a distance of 120,546 miles (194,000 km) from Saturn — that’s about half the distance between Earth and the Moon.

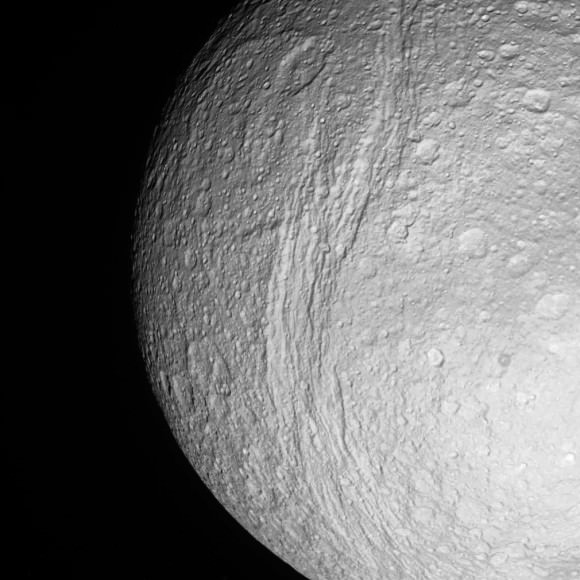

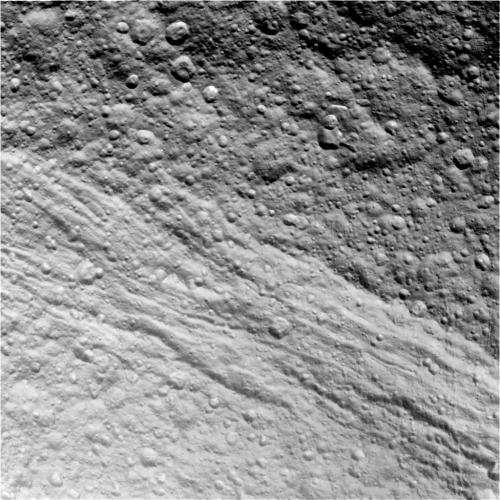

At an altitude of 1,200 miles (1900 km) this was Cassini’s closest pass ever of Methone, a rare visit that occurred after the spacecraft departed the much larger Tethys.

Along with sister moons Pallene and Anthe, Methone is part of a group called the Alkyonides, named after daughters of the god Alkyoneus in Greek mythology. The three moons may be leftovers from a larger swarm of bodies that entered into orbit around Saturn — or they may be pieces that broke off from either Mimas or Enceladus.

Earlier on Sunday, May 20, Cassini paid a relatively close visit to Tethys (pronounced tee-this), a 662-mile (1065-km) -wide moon made almost entirely of ice. One of the most extensively cratered worlds in the Solar System, Tethys’ surface is dominated by craters of all sizes — from the tiniest to the giant 250-mile (400-km) -wide Odysseus crater — as well as gouged by the enormous Ithaca Chasma, a series of deep valleys running nearly form pole to pole.

Cassini passed within 34,000 miles (54,000 km) of Tethys on May 20, before heading to Methone and then moving on to its new path toward Titan, a trajectory that will eventually take it up out of Saturn’s equatorial plane into a more inclined orbit in order to better image details of the rings and Saturn’s poles.

Read more about this flyby on the Cassini mission site here. and see more raw images straight from the spacecraft on the CICLOPS imaging lab site here.

Image credit: NASA / JPL / Space Science Institute. (Color-composite image edited by J. Major.)

Is there a limit to how big a rock is before it is considered a moon, or a definition of a moon like there is for planets?

I’ve seen smaller rocks in orbit of asteroids referred to as moons on occasion. Not sure if that was just the article author or official, however. My take is “if it orbits a body that isn’t a star, its a moon”, but I’m very far from being an authoritative source for these things. 😀

From what I have heard, if it’s a natural satellite of another body — even if temporarily — it can be called a moon.

There must be as I know that there are some objects in the ring system house sized (?) and they aren’t considered moons as far as I’m aware which isn’t really a long trip at all… lol. Maybe I’m remembering wrong…?

The small bodies found in the A and B Rings, between ~40 and 500 meters in diameter, have been referred to as “moonlets”:

http://saturn.jpl.nasa.gov/photos/imagedetails/index.cfm?imageId=3617

http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v440/n7084/full/nature04581.html

http://arxiv.org/pdf/0710.4547.pdf

I guess there are major moons and minor moons.

Methone has an interesting shape. Very oblate.

I wonder what accounts for the relative smoothness of this tiny moon? Large craters seem to be absent in this view. Why isn’t it peppered with craters like the nearby moons Mimas and Enceladus or, as pictured above, Tethys?

[added on edit]

Perhaps the smoothness is due to resurfacing from Methone’s orbit within the E ring (interior to Enceladus) or, specifically the Methone Ring Arc: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rings_of_Saturn#Methone_Ring_Arc

It might be that this image is of the leading hemisphere of Methone, with a more rugged, battered trailing hemisphere hiding in the shadows.

Dude that jsut looks cool!

http://www.Total-Privacy dot US