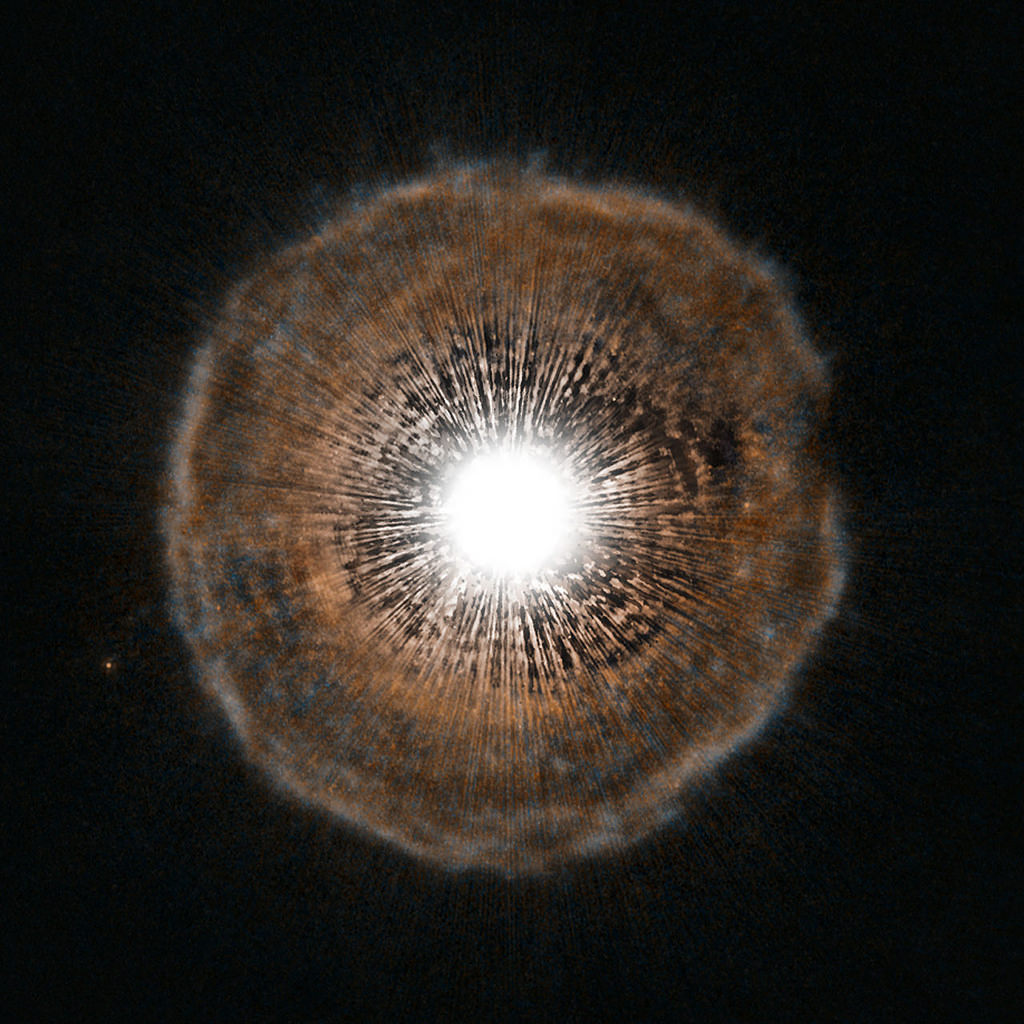

As stars approach the inevitable ends of their lives they run out of stellar fuel and begin to lose a gravitational grip on their outermost layers, which can get periodically blown far out into space in enormous gouts of gas — sometimes irregularly-shaped, sometimes in a neat sphere. The latter is the case with the star above, a red giant called U Cam in the constellation Camelopardalis imaged by the Hubble Space Telescope.

From the Hubble image description:

From the Hubble image description:

U Cam is an example of a carbon star. This is a rare type of star whose atmosphere contains more carbon than oxygen. Due to its low surface gravity, typically as much as half of the total mass of a carbon star may be lost by way of powerful stellar winds. Located in the constellation of Camelopardalis (The Giraffe), near the North Celestial Pole, U Cam itself is actually much smaller than it appears in Hubble’s picture. In fact, the star would easily fit within a single pixel at the center of the image. Its brightness, however, is enough to saturate the camera’s receptors, making the star look much bigger than it really is.

The shell of gas, which is both much larger and much fainter than its parent star, is visible in intricate detail in Hubble’s portrait. While phenomena that occur at the ends of stars’ lives are often quite irregular and unstable, the shell of gas expelled from U Cam is almost perfectly spherical.

Image credit: ESA/NASA

Fantastic photo!

it’s like watching sun through Riddick’s glasses.. 🙂

Makes me want to blow on it to spread the seeds in the Summer wind…

planet seeds

blown with the wind

… carbon life

This is a shockingly understated article both by the ESA/ NASA press release and by UT!

Instead of cursing the author(s), let’s just be precise here…

There is little to no background work and little of the size nor origins of the outer shell.

For example;

Also, the term “powerful stellar winds” are normally termed “superwinds” (>1000 km.s^-1).

Need I say more… 😮

Another point. Why is the tag “supernova” given as a keyword here?

U Cam will never go supernova, it is far too small in mass. Moreover, the mass loss is more related to planetary nebulae and processes of standard stellar evolution theory.

Because it relates to processes of mass loss, one may assume.

The process is not like supernovae, which ejects all of the outer layers due to the energy in the core collapse. Mass loss through superwinds are caused by separate mechanisms akin to the solar wind. When star swell to red giants their outer atmospheres are far more tenuous, therefore accelerating the mass loss and the material velocities. It is a natural process in stellar evolution in the AGB phases.

Physicist Sean Carroll’s 2nd Axiom of blog comments comes to mind… http://blogs.discovermagazine.com/cosmicvariance/2012/06/26/comment-policy/

Hey. None of this is nothing like personal theory. I admit I do like stories that say “that sounds interesting”, let’s see what else I can learn about it. I like stories, too, that just paint me a picture. In 2010, I had already read Olofsson et al., “High-resolution HST/ACS images of detached shells around carbon stars.” http://arxiv.org/pdf/1003.0362v1.pdf It discusses the image and how it was obtained, and enough info to make a far more informative and educational article. [The shell being only 700 years old is probably the most relevant.] It seems these images were taken in January 2005 – seven years ago – but press released as a colour image just a few days ago. Your article here and the press release, IMO, glosses over the readily available material. I don’t know why.

I think the problem is that your constructive criticism often comes across as quite rude. Instead of starting your comment with “Hey! You clumsily forgot to mention…” maybe try using “Also, did you know that…?”. Then your comment will look less like an obnoxious review and more like a helpful piece of content that others (including the author) can enjoy.

Your second comment has a similar rudeness to it: “Why does the article say [thing]? That’s wrong.” There’s no need to phrase it as a question, because if it is wrong, then the answer is “it was a mistake”. Instead of asking why the author made a mistake, try pointing out that s/he made one.

…but the author NOT did make a mistake, and I have no claimed otherwise. In fact, it is factually correct.

Again, as my first comment says, it is “understated.” My point is that it is incomplete. Jason here has just been openly recreated as an article and release from ESA/NASA. Here, the fault lies equally with them too – probably being another example of dumbing down material to much for public consumption.

I continue to be amazed at the media continues to sideline the science and make it so clinically clean that it say nothing really about the subject. I.e. Torbjörn Larsson comment above on supernovae shows the distinct lack of explanation – leaving the option that people have to make up their minds instead of being educated or told about it.

IMO all science is being decimated by both the media social media, and among the general public it continues to be degraded but not explaining the facts. (I suspect this story deliberately avoids any controversy.

Sure it is a pretty picture, but it is far more interesting than that. Jason and the others at UT have a very important role to play in promoting science this highly popular website. Nearly all of their stories are really good journalism, but now and again they fail in their thoroughness. Doing ones own homework is important. So somy apologies if I sound rude. I was just trying to be direct to the point.

The main thing is that not all articles are intended to be comprehensive analyses of all known data regarding a topic. Some may just be a “hey, check this out” brief — especially when an image is involved. It’s not automatically assumed that readers have independently read the related research papers.

Like Prof. Carroll said, it’s a big internet out there and everyone is coming to a post with different expectations. A blogger can’t meet everybody’s 100%, as someone who wants more may get less and vice versa. The best we can hope for is an enjoyable experience for most.

I think we do pretty well here at UT. 🙂

Please read my response above to squidgeny.

Yes, I entirely agree. UT generally does a very good presenting the stories – hence the high popularity of the site. I do read all the stories and most of the comments, and I come back for more because they so informative. Some stories I use as stepping-boards, and go and investigate the story in far more detail. This is either reading a few scientific papers or published stories like ScienceDaily, etc.

This story of U Cam got to me, because it is one of the few stories I already knew something about. Yet the relevant papers on this object are so easy to find in a search engine like Google, that anyone could use the information to their great advantage – setting out the story for them rather from the similar spoon-feed versions given in other science sources like UT.

Will tact may not be my strong suit, my point nonetheless is relevant and in my mind needed to be stated.

This looks more like the birth of a new star. As the star reaches critical mass, all that new explosive energy is “shedding” itself of the outer-most layers of star material – whatever that may be.

This process doesn’t happen instantaneously, which is why that layer of expelled material is so thick – yet relatively evenly distributed.

When a new star first ignites, at some point that explosive force originating from the star’s depths will relentlessly push the surface layers hard enough and far enough to look just like the photo we see here.