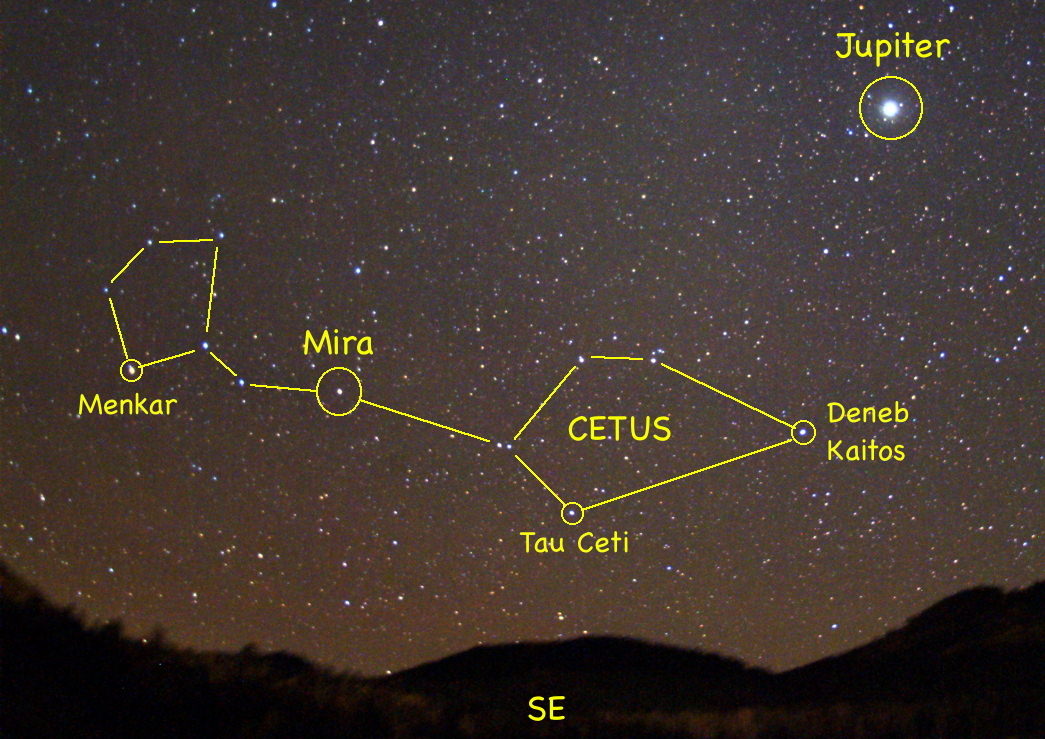

The location of Tau Ceti in the night sky. Credit: University of Hertfordshire

Look up in the sky tonight towards the southeast in the constellation Cetus. There’s a naked-eye star named Tau Ceti that lies about 12 light-years away from Earth, and astronomers have discovered a system of at least five planets orbiting Tau Ceti, including one in the star’s habitable zone.

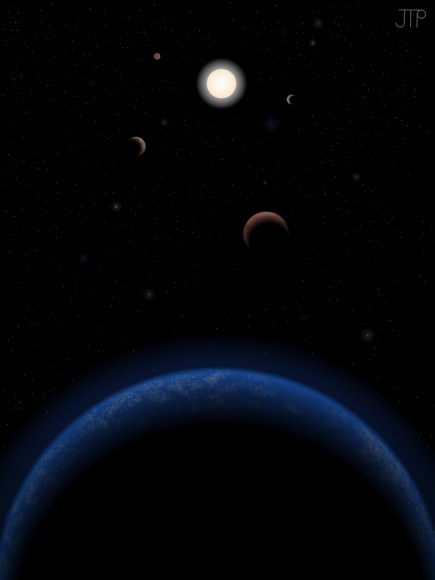

While the recent discovery of a Earth-sized planet around the triple star system Alpha Centauri is the closest planet that has been discovered at just 4.3 light years away, this new discovery is the closest single sun-like star that we know of to host of an entire system of planets. The five planets are estimated to have masses between two and six times the mass of the Earth, making it the lowest-mass planetary system yet detected. The planet in the habitable zone of the star has a mass around five times that of Earth, making it the smallest planet found to be orbiting in the habitable zone of any Sun-like star.

“This discovery is in keeping with our emerging view that virtually every star has planets, and that the galaxy must have many such potentially habitable Earth-sized planets,” said astronomer Steve Vogt from UC Santa Cruz, coauthor of the paper describing the discovery. “We are now beginning to understand that nature seems to overwhelmingly prefer systems that have multiple planets with orbits of less than 100 days. This is quite unlike our own solar system, where there is nothing with an orbit inside that of Mercury. So our solar system is, in some sense, a bit of a freak and not the most typical kind of system that Nature cooks up.”

An artist’s impression of the Tau Ceti system. (Image by J. Pinfield for the RoPACS network at the University of Hertfordshire.)

Tau Ceti has long been a target of both detailed astronomical study and hopeful science fiction, since it is among one of the 20 closest stars to Earth. It is also easily visible to the naked eye and can be seen from both the Northern and Southern Hemisphere. During the 1960’s, Project Ozma, led by SETI’s Frank Drake, probed Tau Ceti for signs of life by studying interstellar radio waves with the Green Bank radio telescope. Science fiction authors like Robert Heinlein, Isaac Asimov and Frank Herbert used Tau Ceti as destinations and focal points in their books.

Scientists know this star has a dusty debris disk at least 10 times more massive than our solar system’s Kuiper Belt, and it has been observed long enough that no planets larger than Jupiter have been found.

An international team of astronomers from the United Kingdom, Chile, United States, and Australia, combined more than six-thousand observations from the UCLES spectrograph on the Anglo-Australian Telescope, the HIRES spectrograph on the Keck Telescope, and reanalysis of spectra taken with the HARPS spectrograph available through the European Southern Observatory public archive.

Using new techniques, the team found a method to detect signals half the size of previous observations, greatly improving the sensitivity of searches for small planets.

“We pioneered new data modeling techniques by adding artificial signals to the data and testing our recovery of the signals with a variety of different approaches,” said lead author Mikko Tuomi of the University of Hertfordshire. “This significantly improved our noise modeling techniques and increased our ability to find low-mass planets.”

Tau Ceti e is the planet in the habitable zone, and its year is about half as long as ours. An independent study of the data from the system done by Abel Méndez at the University of Puerto Rico at Arecibo says that the fifth planet, Tau Ceti f, may also be in the habitable zone.

While over 800 planets have been discovered orbiting other worlds, planets in orbit around the nearest Sun-like stars are particularly valuable to study, the team said.

“Tau Ceti is one of our nearest cosmic neighbors and so bright that we may be able to study the atmospheres of these planets in the not-too-distant future. Planetary systems found around nearby stars close to our Sun indicate that these systems are common in our Milky Way galaxy,” said James Jenkins of Universidad de Chile, a visiting fellow at the University of Hertfordshire.

The team’s paper that has been accepted for publication in Astronomy & Astrophysics.

Read the team’s paper: Signals embedded in the radial velocity noise (pdf file) or here on arVix

Sources: University of California Santa Cruz, University of Hertfordshire

On Monday, Philip Gregory at the University of British Columbia in Canada posted an as-yet unpublished paper to the arXiv repository, claiming to have seen three planets in the habitable zone of Gliese 667C, one of three stars in a triple-star system, 22 light-years away.

http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/science-environment-20770103

It has been claimed that the system as seen by Gregory would be unstable.

No one has “seen” any terrestrial class extrasolar planets yet.

All we have are the perturbations caused to star by the planets gravity which make the star to “wobble”.

To actually see planets would need something like an upgraded TPF mission which was scrapped to fund the SLS / Orion.

This is really exciting! Although it seems we won’t find out for a long time what life will be on the planet it’ll be great to have information about it and learn more about these exo-planets.

“Tau Ceti is one of our nearest cosmic neighbors and so bright that we may be able to study the atmospheres of these planets in the not-too-distant future. ”

Very soon, we will be able to know if there is life on this planet. The atmosphere will tell us if there is life.

Is there life on Mars? Titan? Maybe, maybe not. But, we can’t tell just by looking at the atmosphere

If we detected significant free oxygen in the atmospheres of Mars or an extrasolar planet, it would be a powerful indication, though…

(Of course O2 and Titan’s methane would be a highly unstable and unlikely state if affairs, though some believe that Titan’s chemistry is ‘out of equilibrium’ in a way that is at least consistent with some sort of life)

We can tell by looking at our own atmosphere’s light, reflected in the Moon, that it has life both because it has oxygen adsorption and because it has a chlorophyll absorption edge.

It is a successful proof of principle, as is oxygen observed on hot planets (too hot for liquid water). It can be done.

Earth’s early atmosphere didn’t have oxygen for some 1.8 billion years (fossils in Australia) and possibly 2.15 billion years (chemical signs of life in Greenland rocks) after life had evolved, so lack of oxygen in atmosphere isn’t a sign of lack of life (in possible seas).

Yes, you have to look at the star’s age. Eg it will work for Tau Ceti,

I hear there are telescopes that may be capable of doing these studies despite there being no priority in the decadal surveys outlining what astronomical resources should be concentrated on.

I hope so! Tau Ceti must be a prime target.

There are a few obvious markers. Lots of oxygen and nitrogen would be a huge find. Add in hints of industrial pollutants and we have an even bigger find.

Let me see, was that Ceti Alpha V, or Ceti Alpha VI?

Please note that of the 6000 data points taken the ESO HARPS(4864 data

points); UCLES on the Anglo-Australian Telescope(978 data points); and

HIRES on the Keck telescope(567 data

points). So roughly 80% of the Data for this announcement comes directly

from ESO. To quote lead author Mikko Tuomi, of the University of

Hertfordshire in England:

“This work would have not been

possible without the ESO public data policies and the excellent work of

the ESO Software development division and the ESO Science Archive

Facility.”

I am happy with the analysis of the HARPS result, but the moving-average model used for the noise correlation is one that does not make sense for very-unevenly-sampled data. Having a single weight for ‘two samples ago’, even with a bit of additional time-scale weighting to account for the fact that ‘two samples ago’ can be a variable amount of time, doesn’t make sense when the variability is large.

But I suspect the HARPS datapoints are fairly evenly sampled within a night and the beta value in section 7.3 means that between-night effects are damped to zero, so the model is good for HARPS. For the HIRES and UCLES data the beta is small enough (IE the between-night damping is small) to make the moving-average model actually invalid.

“We are now beginning to understand that nature seems to overwhelmingly prefer systems that have multiple planets with orbits of less than 100 days.” – Isn’t this a function of our planet finding techniques and not necessarily an actual characteristic of stars?

According to Wikipedia, this star is moving towards us at 16km/s. So, if we wait about 20,000 years, we should be able to see for ourselves what these planets look like.

To some extent it is a function of our planet finding techniques. However… If we were only finding one close-in planet per star, one could say “Well, large close-in planets are rare, but those are we are seeing. Our solar system is still normal!” But with multiple examples of stars having 4-6 planets crammed closer than Mercury is to the Sun, it can no longer be explained by the observer bias.

This system is little of both though.

Tau Ceti e has twice the 100 orbit time, and f has twice the year we have. The only difference is that it has more “mercury” planets.

. . . Exactly. Most systems we’ve looked at have multiple Mercury-type planets, where we only have one.

Or Jupiter sized Mercury planets?

From the abstract of the paper (http://star-www.herts.ac.uk/~hraj/tauceti/paper.pdf):

These periodicities could be interpreted as corresponding to planets on dynamically stable close-circular orbits with periods of 13.9, 35.4, 94, 168, and 640 days and minimum masses of 2.0, 3.1, 3.6, 4.3, and 6.6 M_? respectively.

The last planet is the planet of interest. The surface gravity is about 1.9 times that of Earth. This makes this planet certainly not good real estate for those who have interstellar colonization ideas. Also at that mass this planet is close to the boundary between a terrestrial planet and a Neptunian type of planet. However, this planet could have a moon that is comparable to Earth in mass that could support life.

Tau ceti also have a rather large planetary disk of material. This means there are probably a lot of comets and asteroids. This might mean there are a lot of impacts on these planets. That could make life a bit tough on this planet.

LC

” minimum masses of 2.0, 3.1, 3.6, 4.3, and

6.6 M_? respectively. The

last planet is the planet of interest”

Isn`t the 4.3 M_? , i.e. the 4th planet, the planet of main

interest? That would put it right in the middle of the “super earth”

range.

If I understood right, the 6.6 M_? 5th planet can also be in the habitable

zone, but this is not sure because the planet is very near the outer (cool)

edge of the HZ

You are right. I was thinking of ?-Ceti a as the first planet, not the star. This is about what the system looks like

planet Mass Semimajor axis (AU) Orbital period (days) Eccentricity

b 2.00 ± 0.79 M? 0.105 ± 0.006 13.965 ± 0.02 0.16 ± 0.22 —

c 3.11 ± 1.40 M? 0.195 ± 0.01 35.362 ± 0.1 0.03 ± 0.03 —

d 3.50 ± 1.59 M? 0.374 ± 0.02 94.11 ± 0.7 0.08 ± 0.26 —

e 4.29 ± 2.00 M? 0.552 ± 0.02 168.12 ± 2.0 0.05 ± 0.2 —

f 6.67 ± 3.50 M? 1.35 ± 0.1 642 ± 30 0.03 ± 0.3 —

and the ?-Ceti e planet looks a bit more reasonable. The surface gravity would be 1.6g, which would be uncomfortable.

LC

The HEC places both as potential habitable candidates, see my previous comment’s link. And yes, the outer one is just slightly better than Mars, but passes their criteria, see their data and the orbit graph posted there.

On the bright side, lots of asteroids also means lots of water on the inner planets. It also suggests that there in no gas giant closer than the outer edge of that asteroid belt, which is a bit anomalous. This would also explain why there is an abundance of terrestrial planets in this system. Perhaps this system was gas, (or ligher element) deprived for reasons not known. Has anyone checked the lithium content of the star, that certainly would be a publication in and of itself. This is certainly an interesting system to study. Colonizinig it, if this data holds up (and that is still a serious issue here as the results of this new technique still must pass the test of reproducibility) would be problematic. There would a ton of work to do in order to move asteroids away from bad orbits before any planet is safe to colonize there. Very long-term project, but worth it as this is a star with a longer life span. I could go on, but these are my first thoughts. Exciting day.

Good guess on giants! It has low metallicity, ~ 50 % of Sun, so will penalize giants.

However, the problem with terrestrials is to keep them dry enough and not to drown them with asteroid water delivery. One order of magnitude more water will start to be hurtful, assuming the planets have tectonics. (And they are large, so they should have.) Not much, if any, land left.

The follow-up question then is: are we seeing more gas giants in torch orbits around high metallicity stars. I believe the awnser is yes, but I would need a much larger smpling size than what I can think of.

I looked into the matter more and will be referring to this article:

http://www.mso.anu.edu.au/~charley/papers/GretherLineweaver2007.pdf

There is a positive correlation with high metallicity stars and Jupiter class companions within 5 AU. The data did not support a correlation with increasing closer distance (torch orbits) and metallicity. The sample size is only 180 systems, however.

My reasoning is that heavier elements have an effect on the protoplanetary disc similar to a catalyst in chemistry. Protoplanets form faster, favoring the formation of fewer and larger plaents. One camp holds that planets in torch orbits form where they are rather than migrate in, a matter which will be resolved once more of their atmospheres are measured. In the meantime, if they do form close in to the star to begin with, then more heavier elements should favor this process and we should see more giants close in to high metallicity stars. The study above supports this, but obviously the sample size is ever-increasing. Lower metallicity stars would in contrast form more and smaller planets close in to the star.

The other concept I keep in mind is the temperature gradient. In my view planets just outside the snow line form more easily and faster and this is the next most likely place to see larger planets. This is where the migrating hot Jupiters would form before they start migrating. In a metal-poor system it would be more likely a Neptune or Saturn sized object that would form outside the snow line.

Planet formation by gravitational instability throws a monkey wrench into this works, but I suspect this is the exception and would apply more commonly to brown dwarf or a star with a comparitively small binary companion in a close orbit. If this were the dominant mechanism of gas giant formation, then their locations should be randomly distributed.

It is actually classified as two habitable planets among astrobiologists, e @ 0.77 ESI and f @ 0.71 ESI. (ESI > 0.7 is considered potentially habitable). [ http://phl.upr.edu/projects/habitable-exoplanets-catalog ]

That system alone provides 22 % of the 9 acknowledged potential habitable planets! Tau Ceti joins Gliese 581 among the exclusive systems which have 2 habitables.

I’m not sure the press release makes sense, but I haven’t read the paper, both habitable planets are well outside the 100 day orbit at 168 and 642 (!) days. I would like to see some statistics, where observational bias is considered, on the 100day orbit claim.

One nice observation is that Tau Ceti has about half the metallicity of Sun.

Tau Ceti is also older than Sun, so you would expect life there. However it has an observed debris disk that is an order of magnitude more dense than ours, so that would be prokaryote life at best due to the continued high impact rate.

“so that would be prokaryote life at best due to the continued high impact rate”

Are you sure? Life on earth recovered quite rapidly after the k-t impact.

If a k-t sized asteroid hit earth now, there would be a mass extinction, but some % of plants and animals (and even a few humans) will survive. In effect, some 30-40 % of advanced lifeforms survived the k-t extinction. Even the biggest mass extinction , the Permo-Triassic “Great Dying” leaved 10% of species alive, and was almost surely due to extreme global warming as a consecuence of massive greenhouse gas emissions by volcanoes (i.e. the Siberian Trapps), not due to an asteroid impact.

Even if every million years the Earth would be hit by a km-sized asteroid, it’s hard to imagine how can all (100%) of plants , protists, fungi and animals could be eliminated, including all worms, insects, grasses, mold, amoebae, etc.

Life is very difficult to destroy.

That is what I use to say!

In haste:

1. The K-Pg impact, as it is now known as, is special. It hit calciferous and sulfurous sediments that only modern life lay down.

2. Modeling feasible impact rates, Mojzic (sp?) et al has prokaryotes surviving up to an order more than we had, quite feasibly the rates Tau Ceti sees. Because they repopulate faster than sterilization can keep up. Especially in the Goldilock zone ~ 1 km down.

Evene mesophiles may take it, albeit at low sustained population levels, so easier to go extinct.

3. We know also nematodes can live in the GZ ~ 1 km down. However, they don’t repopulate and disperse as easily.

4. Eukaryotes needs ~ 1 M year to recover diversity after mass extinctions.

#2 means life is virtually indestructible. Life is a plague on a planet!

#3 means multicellulars are not so happily endowed. Maybe, maybe not.

If complex eukaryotes can appear despite a much longer initial bombardment tailing off and delaying, yes, #4 may mean they would take 10 as much impactors today and keep going.

I’m willing to modify my initial analysis: Complex life possible, takes longer to appear, may not be as likely.

Thanks for making me reconsider!

Perhaps, if these planets are habitable but are being repeatedly bombarded, complex life would find ways of adapting to the relatively frequent hits. Perhaps the reason why these events are so disastrous on Earth is because they’re so rare. It’s all speculation, but it’s fun to guess.

Gliese 581 has at least 3, possibly 4, planets in it’s habitable zone. It might be thát the innermost could be a “Super-Venus”, but as we don’t have any actual evidence of that, I wouldn’t yet close any of those planets out from the ranks of possibly habitable planets.

Thanks. Different scientists will come to different conclusions. (Which the post shows.)

Maybe I should say ESI habitability. (As in: ESI > 0.7.)

I have a guess that Venus actually IS inside the habitable zone. What went wrong there was likely the failure to sustain plate tectonics.

Without plate tectonics, the carbon cycle just got crazy, as CO2 accumulated without fresh rocks sequestering it as carbonates (via the CO2 chemical weathering of silicates*) and runaway greenhouse effect followed.

*chemical weathering of silicates: are reactions that remove dissolved CO2 from rainwater, like:

CaSiO3(solid)+ CO2(aqueous) =CaCO3(solid) + SiO2(solid)

Diana Valencia modelled rocky planet mantle dynamics and found that Earth is just barely tectonically active. Bigger planets are hotter, so and due to the resulting stronger convection would have more active plate tectonics. Also, planets like Earth need water as lubricant to have active plate tectonics, while super-earths do not.

Venus is just a little smaller than Earth and perhaps also dryier after its formation. That could have been the cause of its hellish fate, more than its shorter distance to the Sun.

Mars on the other hand is also too small, and with a weaker gravity it and almost no magnetic field ,lost most of its atmosphere to space (unlike Venus), resulting in a frozen planet.

I guess that planets like Earth or bigger could be habitable even in orbits like Mars or Venus. However I am no expert, so maybe I am too optimist.

We keep finding planets that are very close to their respective stars and astronomers have started thinking that we might be the oddball having such huge orbits. But I wonder… Could it be that the other star systems might have many other Saturn or Jupiter sized planets at 30 years orbits and we simply don’t posses the necessary abilities to discover them at this moment? Cause a dip in brightness that wouldn’t be seen in another 10 years might be considered as just a fluke, and the event would be discarded. If a dip in brightness would even occur at that large orbits.

A previous search for faint companions to Tau Ceti using the Wide Field Planetary Camera 2 on the Hubble Space Telescope came up empty: http://iopscience.iop.org/1538-3881/119/2/906/pdf/990423.web.pdf

I wonder if this new finding might lead to a re-examination of Tau Ceti with HST using the more sensitive Wide Field Camera 3?

Scientists agree that Pion antimatter powered spacecraft may approach the speed of light.

The late Dr. Robert Carroll, a mathematical physicist who rejected relativity,

claimed a Pion powered spacecraft might approach 20 million times the speed of light.

See pages 34-37 at CHEAP GREEN on http://www.aesopinstitute.org

Pion fusion is under development in Australia and also by a Japanese –

British Joint Venture.

If successful, spacecraft will surely be powered by Pion drives.

A test craft that might prove Dr. Carroll correct, should it accelerate well beyond

the speed of light, would open human exploration of Goldilocks planets.

these are the things that i love to see posted up. thanks. I wanted to

let you know about some killer traffic video courses i have. just swing

by and take advantage of my save the family vacation firesale. right

now.