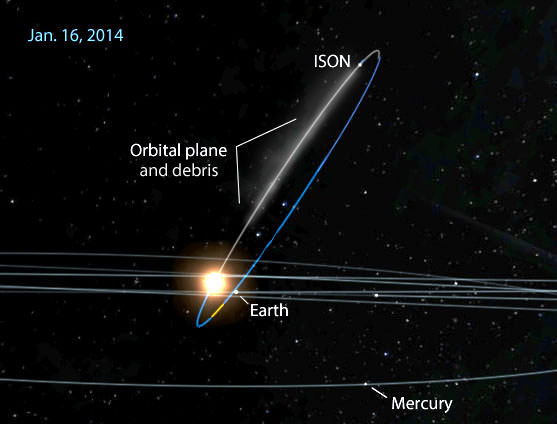

Is there any hope of detecting what’s left of Comet ISON after the sun proved too much for its delicate constitution? German amateur astronomer Uwe Pilz suggest there remains a possibility that a photographic search might turn up a vestige of the comet when Earth crosses its orbital plane on January 16, 2014.

Update: See an image below taken by Hisayoshi Kato of the comet’s location in Draco on December 29!

On and around that date, we’ll be staring straight across the sheet of debris left in the comet’s path. Whatever bits of dust and grit it left behind will be “visually compressed” and perhaps detectable in time exposure photos using wide-field telescopes. To understand why ISON would appear brighter, consider the bright band of the Milky Way. It stands apart from the helter-skelter scatter of stars for the same reason; when we look in its direction, we peer into the galaxy’s flattened disk where the stars are most concentrated. They stack up to create a brighter band slicing across the sky. Similarly, dust shed by Comet ISON will be “stacked up” from Earth’s perspective on the 16th.

This isn’t the first time a comet has leapt in brightness at an orbital plane crossing. You might recall that Comet C/2011 L4 PanSTARRS temporarily brightened and assumed a striking linear shape when Earth passed through its orbital plane on May 27.

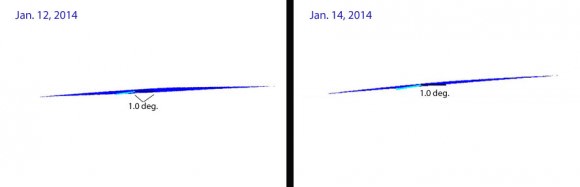

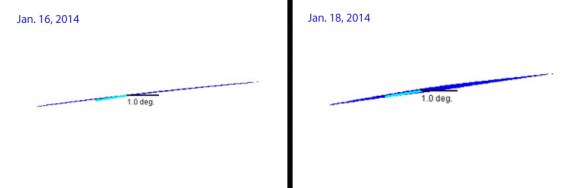

Pilz, a longtime contributor to the online Comets Mailing List for dedicated comet observers, has made a series of simulations of Comet ISON for mid-January using his own comet tail program. He bases his calculations on presumed larger particle sizes 1 mm – 10 mm – not the more common 0.3-10 micrometer fragments normally shed by comets. The assumption here is that ISON has remained virtually invisible since perihelion because it broke up into a smaller number of larger-than-usual pieces that don’t reflect light nearly as efficiently as larger amounts of smaller dust particles.

The images look bizarre at first glance but totally make sense given the unique perspective. Notice that the debris stream becomes thinner as we approach orbital crossing; any potential dust blobs appear exactly edge-on similar to the way Saturn’s rings narrow to a “line” when Earth passes through the ring plane.

Besides the fact that not a single Earth-bound telescope has succeeded to date in photographing any of ISON’s debris, amateurs who attempt to fire one last volley the comet’s way will face one additional barrier – the moon. A full moon the same day as orbital crossing will make a difficult task that much more challenging. Digital photography can get around moonlight in many circumstances, but when it comes to the faintest of the faint, the last thing you want in your sky is the high-riding January moon. One night past full, a narrow window of darkness opens up and widens with each passing night.

Will anyone take up the challenge?

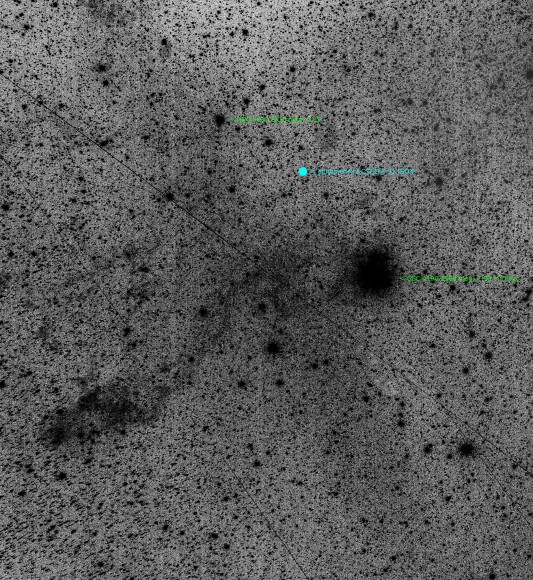

UPDATE Dec. 30 10 a.m. (CST): We may have our very first photo of Comet ISON from the ground! Astrophotographer Hisayoshi Kato made a deep image of the comet’s location in Draco on December 29 using a 180mm f/2.8 telephoto lens near the Mauna Loa Observatory in Hawaii at 11,000 feet. He stacked 5 exposures totaling 110 minutes to record what could be the ISON’s debris cloud. It’s incredibly diffuse and faint and about the same brightness as the Integrated Flux Nebula, dust clouds threading the galaxy that glow not by the light of a nearby star(s) but instead from the integrated flux of all the stars in the Milky Way. We’re talking as dim as it gets. What the photo recorded is only a tentative identification – followup observations are planned to confirm whether the object is real or an artifact from image processing. Stay tuned.