Since their discovery, supermassive black holes – the giants lurking in the center of every galaxy – have been mysterious in origin. Astronomers remain baffled as to how these supermassive black holes became so massive.

New research explains how a supermassive black hole might begin as a normal black hole, tens to hundreds of solar masses, and slowly accrete more matter, becoming more massive over time. The trick is in looking at a binary black hole system. When two galaxies collide the two supermassive black holes sink to the center of the merged galaxy and form a binary pair. The accretion disk surrounding the two black holes becomes misaligned with respect to the orbit of the binary pair. It tears and falls onto the black hole pair, allowing it to become more massive.

In a merging galaxy the gas flows are turbulent and chaotic. Because of this “any gas feeding the supermassive black hole binary is likely to have angular momentum that is uncorrelated with the binary orbit,” Dr. Chris Nixon, lead author on the paper, told Universe Today. “This makes any disc form at a random angle to the binary orbit.

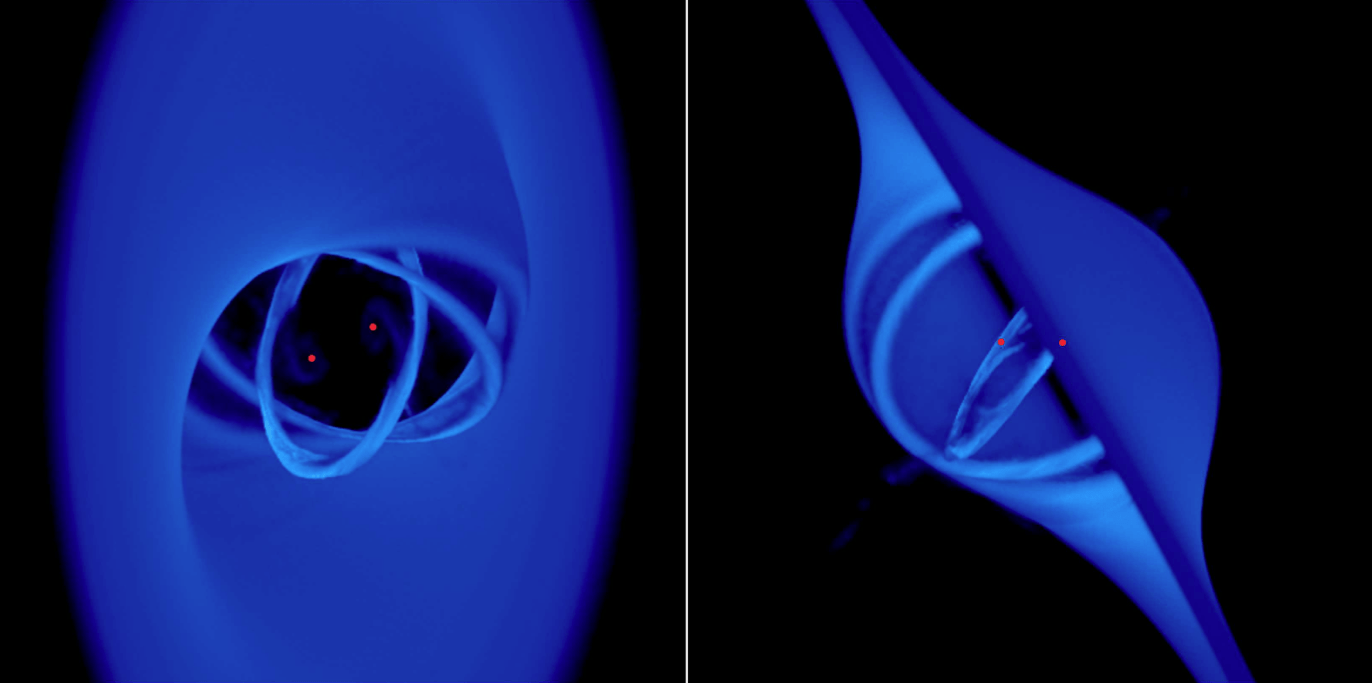

Nixon et al. examined the evolution of a misaligned disk around a binary black hole system using computer simulations. For simplicity they analyzed a circular binary system of equal mass, acting under the effects of Newtonian gravity. The only variable in their models was the inclination of the disk, which they varied from 0 degrees (perfectly aligned) to 120 degrees.

After running multiple calculations, the results show that all misaligned disks tear. Watch tearing in action below:

In most cases this leads to direct accretion onto the binary.

“The gravitational torques from the binary are capable of overpowering the internal communication in the gas disc (by pressure and viscosity),” explains Nixon. “This allows gas rings to be torn off, which can then be accreted much faster.”

Such tearing can produce accretion rates that are 10,000 times faster than if the exact same disk were aligned.

In all cases the gas will dynamically interact with the binary. If it is not accreted directly onto the black hole, it will be kicked out to large radii. This will cause observable signatures in the form of shocks or star formation. Future observing campaigns will look for these signatures.

In the meantime, Nixon et al. plan to continue their simulations by studying the effects of different mass ratios and eccentricities. By slowly making their models more complicated, the team will be able to better mimic reality.

Quick interjection: I love the simplicity of this analysis. These results provide an understandable mechanism as to how some supermassive black holes may have formed.

While these results are interesting alone – based on that sheer curiosity that drives the discipline of astronomy forward – they may also play a more prominent role in our local universe.

Before we know it (please read with a hint of sarcasm as this event will happen in 4 billion years) we will collide with the Andromeda galaxy. This rather boring event will lead to zero stellar collisions and a single black hole collision – as the two supermassive black holes will form a binary pair and then eventually merge.

Without waiting for this spectacular event to occur, we can estimate and model the black hole collision. In 4 billion years the video above may be a pretty good representation of our collision with the Andromeda galaxy.

The results have been published in the Astrophysical Journal Letters (preprint available here). (Link was corrected to correct paper on 8/15/2013).

While this is an interesting model of the forces that drive accretion in certain systems, I do not see that this paper necessarily has any implications for the mechanism behind the initial formation of SMB’s. Nor do I see anything at all in this paper about the mergers of SMB’s. Certainly the paper’s authors nowhere claim that this mechanism could turn a stellar-mass black hole into a supermassive one.

I agree with your statement completely. This article does not specifically outline the process. I have not read the original paper at this point, and wonder if this was their intent at all. If Nixon does make this claim, this article does little to explain his work. If he does not make this claim, this article needs to be followed up by a “correction” article.

That being said, I wonder how interactions between two stellar-mass binaries in a large highly dense region (such as a globular cluster) would interact. Would they create a similar dynamic in which they could steadily accrete matter?

I am interested in reading the original paper to understand if they are in fact looking into this possibility, or if this article was simply a mis-understanding of the Nixon et. al. paper.

People have recently found BHs in the intermediate region as reported here on UT, IIRC. I haven’t time to check this, but my impression whether mistaken or not is that a remaining problem has been to predict the necessary growth rates. This seems to be a suggestion of a possible solution for such a problem.

What about the ‘Singularity’ ?

What about it? This paper is about the dynamics of of accretion disks and says nothing about any process within the event horizon.

I have read the paper, and they make no such claims. All they are talking about is 1) in stellar-mass binaries this process will not speed up accretion, which is more related to the viscosity of the outer ring of the accretion disc, but may regulate the inflow, and 2) in active galactic nuclei this process may speed accretion of material which otherwise might never fall in. They make no claims about stellar-mass black holes becoming SMBs, nor do they even mention SMB binaries created in galactic collisions.

[b]Disclaimer:[/b] I am not an astrophysicist, so it is possible that this process has implications not spelled out in the paper that I have missed. But if the author of this article is making claims based on her own research beyond those made in the paper, she should tell us that.

We inadvertently linked to the wrong paper initially, but have now corrected it. The paper can be found at http://arxiv.org/abs/1307.0010

Thank you for this correction, although I think such corrections should be clearly noted within the text of the article and not merely in the comments. The newly-linked paper does indeed seem to support the claims of he article, with modeling showing that accretion discs in certain alignments (and perhaps multiple randomly-aligned accretion events) may result in tearing that can increase accretion by a factor of 10^4 and make it possible for mergers between binary black holes resulting from galaxy mergers to occur within the Hubble time. That is very interesting indeed, and fills in some holes in our understanding.

Please check Nancy Atkinson’s comment below for the correct link to the paper in question. The paper originally cited and on which I based my comment was apparently not the correct one.