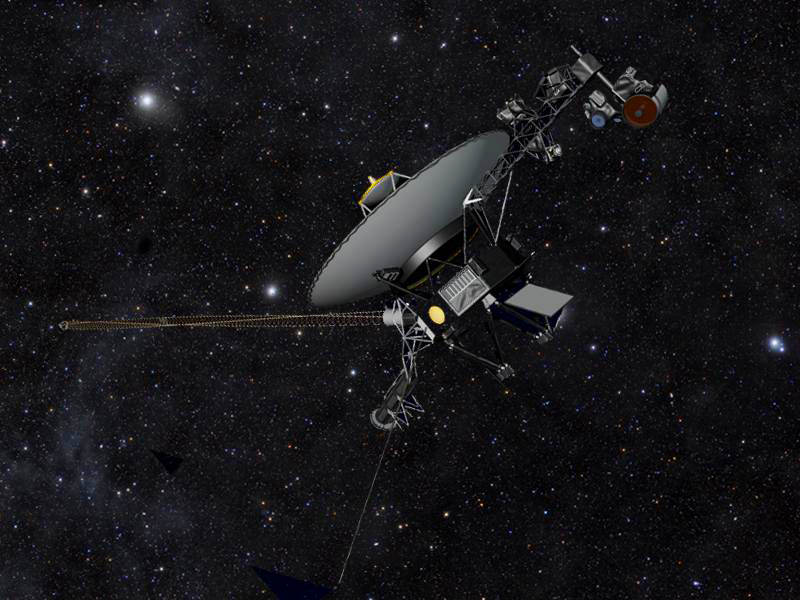

Nearly 18.7 billion kilometers from Earth — about 17 light-hours away — NASA’s Voyager 1 spacecraft is just about on the verge of entering interstellar space, a wild and unexplored territory of high-energy cosmic particles into which no human-made object has ever ventured. Launched in September 1977, Voyager 1 will soon become the first spacecraft to officially leave the Solar System.

Or has it already left?

I won’t pretend I haven’t heard it before: Voyager 1 has left the Solar System! Usually followed soon after by: um, no it hasn’t. And while it might all seem like an awful lot of flip-flopping by supposedly-respectable scientists, the reality is there’s not a clear boundary that defines the outer limits of our Solar System. It’s not as simple as Voyager rolling over a certain mileage, cruising past a planetary orbit, or breaking through some kind of discernible forcefield with a satisfying “pop.” (Although that would be cool.)

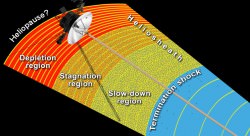

Rather, scientists look at Voyager’s data for evidence of a shift in the type of particles detected. Within the transitionary zone that the spacecraft has most recently been traveling through, low-energy particles from the Sun are outnumbered by higher-energy particles zipping through interstellar space, also called the local interstellar medium (LISM). Voyager’s instruments have been detecting dramatic shifts in the concentrations of each for over a year now, unmistakably trending toward the high-energy end — or at least showing a severe drop-off in solar particles — and researchers from the University of Maryland are claiming that this, along with their model of a porous solar magnetic field, indicates Voyager has broken on through to the other side.

Read more: Voyagers Find Giant Jacuzzi-like Bubbles at Edge of Solar System

“It’s a somewhat controversial view, but we think Voyager has finally left the Solar System, and is truly beginning its travels through the Milky Way,” said Marc Swisdak, UMD research scientist and lead author of a new paper published this week in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

According to Swisdak, fellow UMD plasma physicist James F. Drake, and Merav Opher of Boston University, their model of the outer edge of the Solar System fits recent Voyager 1 observations — both expected and unexpected. In fact, the UMD-led team says that Voyager passed the outer boundary of the Sun’s magnetic influence, aka the heliopause… last year.

Read more: Winds of Change at the Edge of the Solar System

But, like some of last year’s claims, these conclusions aren’t shared by mission scientists at NASA.

“Details of a new model have just been published that lead the scientists who created the model to argue that NASA’s Voyager 1 spacecraft data can be consistent with entering interstellar space in 2012,” said Ed Stone, Voyager project scientist at Caltech, in a press release issued today. “In describing on a fine scale how magnetic field lines from the sun and magnetic field lines from interstellar space can connect to each other, they conclude Voyager 1 has been detecting the interstellar magnetic field since July 27, 2012. Their model would mean that the interstellar magnetic field direction is the same as that which originates from our sun.

“Other models envision the interstellar magnetic field draped around our solar bubble and predict that the direction of the interstellar magnetic field is different from the solar magnetic field inside. By that interpretation, Voyager 1 would still be inside our solar bubble.”

Stone says that further discussion and investigation will be needed to “reconcile what may be happening on a fine scale with what happens on a larger scale.”

Whether still within the Solar System — however it’s defined — or outside of it, the bottom line is that the venerable Voyager spacecraft are still conducting groundbreaking research of our cosmic neighborhood, 36 years after their respective launches and long after their last views of the planets. And that’s something nobody can argue about.

“The Voyager 1 spacecraft is exploring a region no spacecraft has ever been to before. We will continue to look for any further developments over the coming months and years as Voyager explores an uncharted frontier.”

– Ed Stone, Voyager project scientist

Built by JPL and launched in 1977, both Voyagers are still capable of returning scientific data from a full range of instruments, with adequate power and propellant to remain operating until 2020.

Read the full UMD news release here, and find out more about the Voyager mission on the NASA/JPL website here.

_____________

Note: The definition of “Solar System” used in this article is in reference to the Sun’s magnetic influence, the heliosphere, and all that falls within its outermost boundary, the heliopause (wherever that is.) Objects farther out are still gravitationally held by the Sun, such as distant KBOs and Oort Cloud comets, but orbit within the interstellar medium.

The Oort Cloud is part of the Solar System – at roughly 1000 times the distance to the edge of the heliosphere. Voyager may be entering the interstellar medium, but it’s still well within the solar system as defined by the Sun’s gravitational influence.

But that neighborhood is just defined by the proximity of our nearest neighbors. If more stars were closer, they would strip away the comets.

Anyway, Voyager is observing winds and fields, not solid objects, so the appropriate contextual definition is being used.

But from your point of view a satellite that has travelled just outside the atmosphere has left Earth. This solar boundary is nothing more than the Sun’s atmosphere.

Yes… that’s the common definition of the “edge of space.” But the Earth’s magnetosphere might be a more apt analogy.

The point isn’t getting to somewhere else, because we know Voyager isn’t going to another star. The point is learning something about the space between stars. How much protection does the Sun’s environment give us? Likewise we know about interplanetary space, which for us starts outside Earth’s magnetosphere.

Don’t worry one of them comes back in Star Trek the original motion picture and much smarter

Already, Voyagers did a great job; it is obvious…

*

Unfortunately, Voyagers will never be able to leave the Solar System…At least, in the our lifetimes… It may be better to spend energy to define the “boundary of a Solar System”, first !

Otherwise, just spending time and energy !

Ok stupid question time here, I’m assuming that objects like Comets that have a large orbit in the hundreds or thousands of years are probably travelling faster than Voyager and yet they eventually come back. What’s stopping Voyager (as well as V2, P1 and P2) from losing momentum and coming back in a few hundred or maybe a thousand years?

Even the sun has a scape velocity, which means that if you travel fast enough, you’ll fly free forever and leave the influence of our sun one day.

Those comets may be very fast once they reach the inner system, but their velocity in the apogee is very very slow.

Right on !!

V’GER, where is V’GER. I have to admit, that was a great flick. I hope it doesn’t get found by the Borg. LOL

“or breaking through some kind of discernible forcefield with a satisfying “pop.”

I’m going to assume if the solar system were surrounded by a film like a soap bubble (and I’m not saying it is), but the force of Voyager 1 hitting even a tenuous membrane at its velocity like that would render it inoperable.

I’m just reading about voyager today, launched since September 1977 over 35 years. I guess voyager is on the verge of leaving the solar system. how signals are being transferred from that distance beats my imagination, good work NASA

its good to know that it will soon leave our territory

Thanks to the title of this column, I am now picturing God holding the door open and getting impatient. 🙂

Whether it’s in or out, it is where it is. My question is ………what are the future plans for Voyager 1?

the probe will not be able to generate enough power to run any single instrument by 2025-2030, so… i geuss future probs will locate it in some other star region…

Voyager’s signals are incredibly faint, yet can still be picked up by the Deep Space Network’s radio antenna in Goldstone, California. Takes about 17 hours for a transmitted signal to reach us!