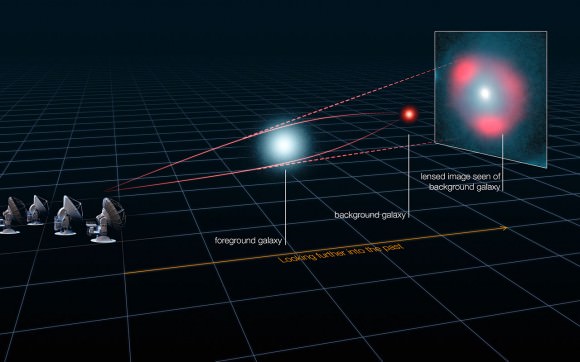

Here’s a picture of what deflected light looks like from 9.4 billion years away. This is the most faraway “gravitational lens” that we know of, and a demonstration of how a galaxy can bend the light of an object behind it. The phenomenon was first predicted by Einstein, and is a handy way of measuring mass (including the mass of mysterious dark matter.)

“The discovery was completely by chance,” stated Arjen van der Wel, who is with the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy in Heidelberg, Germany.

“I had been reviewing observations from an earlier project when I noticed a galaxy that was decidedly odd. It looked like an extremely young galaxy, but it seemed to be at a much larger distance than expected. It shouldn’t even have been part of our observing program.”

The alignment between object J1000+0221 and the object in behind is so perfect that you can see rings of light being formed in the image. Scientists previously believed this kind of lens would happen very rarely. This leaves two possibilities: that the astronomy team was lucky, or there are way more young galaxies than previously thought.

“Gravitational lenses are the result of a chance alignment. In this case, the alignment is very precise,” a press release on the discovery stated.

“To make matters worse, the magnified object is a starbursting dwarf galaxy: a comparatively light galaxy … but extremely young (about 10-40 million years old) and producing new stars at an enormous rate. The chances that such a peculiar galaxy would be gravitationally lensed is very small. Yet this is the second starbursting dwarf galaxy that has been found to be lensed.”

“This has been a weird and interesting discovery,” added van der Wel. “It was a completely serendipitous find, but it has the potential to start a new chapter in our description of galaxy evolution in the early universe.”

The research will be available soon in the Astrophysical Journal; in the meantime, check out a preprint version on Arxiv.