Last week I held an interview with Dr. Sara Seager – a lead astronomer who has contributed vastly to the field of exoplanet characterization. The condensed interview may be found here. Toward the end of our interview we had a lengthy conversation regarding the future of exoplanet research. I quickly realized that this subject should be an article in itself.

The following is a list of approved missions that will continue the search for habitable worlds, with input from Dr. Seager about their potential for finding planets that might harbor life.

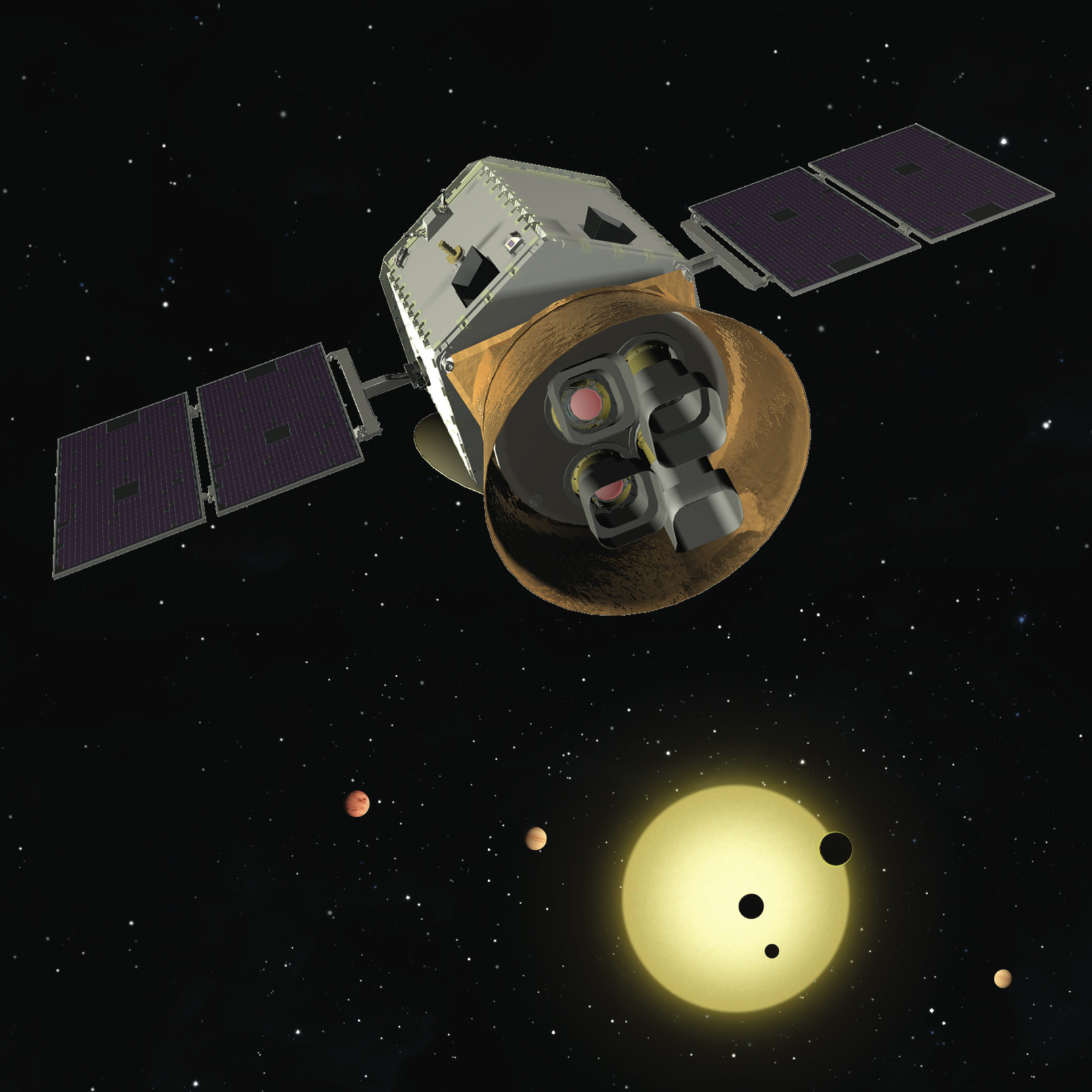

Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS)

Slated to launch in 2017, TESS will search for exoplanets by looking for faint dips in brightness as the unseen planet passes in front of its host star. With a price tag of $200 million, TESS will be the first space-based mission to scan the entire sky for exoplanets.

While the Kepler space telescope confirmed hundreds of exoplanets (with thousands of candidates yet to be confirmed) it stared 3000-light-years deep into a single patch of sky. TESS will scan hundreds of thousands of the brightest and closest stars in our galactic neighborhood.

“TESS will find many planets,” explained Seager in our interview. “The ones we’re highlighting it will find are rocky planets transiting small stars.” One of the missions goals is to find earth-like exoplanets in the habitable zone – the band around a star where water can exist in its liquid state.

The team hopes that TESS will find up to 1000 exoplanets in the first two years of searching. This will give astronomers a wealth of new worlds to study in more detail.

While the stars Kepler examined were faint and difficult to study in follow-up observations, the stars TESS will focus on are bright and close to home. These stars will be prime targets for further scrutiny with other space based telescopes.

“We plan to have a pool of planets, maybe a handful of them, that we can follow up with the James Webb Space Telescope … which will look at the atmospheres of those transiting planets, looking for signs of life,” Seager said.

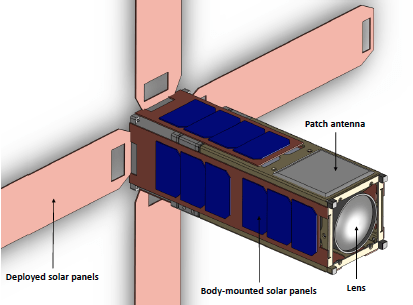

ExoplanetSat

While slightly under the radar, ExoplanetSat will monitor bright stars using nano-satellites. Each nano-satellite will be capable of monitoring a single, bright, sun-like star for two years.

“The way that we describe this mission is not that we will find earth,” Seager said. “But if there is a transiting earth-like planet around a bright sun-like star, we will find it.”

Currently no planned mission has the capability to survey the brightest stars in the sky. TESS will observe stars of magnitude 5 through 12 – the dimmest our eyes can see and fainter.

The brightest stars are too widely spaced for a single telescope to continuously monitor. The best method is to monitor the brightest sun-like stars in a targeted star search instead.

The mission is pretty far along in terms of funding. It has already received a few million dollars and is about one million short of launching the first prototype.

After a successful demonstration the goal is to launch a fleet of nano-satellites to observe enough bright stars to find a number of interesting exoplanets. One day we may be able to look at a bright star in our night sky and know it has a planet.

Direct Imaging Missions

Disentangling a faint, barely reflective, exoplanet from its overwhelmingly bright host star in a direct image seems nearly impossible. A common analogy is looking for a firefly next to a searchlight across North America. Needless to say, very few exoplanets have been seen directly.

Because of the difficulties NASA is fostering a study and soliciting applications with a single goal in mind: create a mission that will directly image exoplanets under a price cap of one billion dollars.

Seager is working with a team that plans to utilize a star shade – “a specially shaped screen that will fly far from the telescope and block out the light from the star so precisely that we will see any planets like earth.”

The shade isn’t circular but shaped like a flower. Light waves would bend around a circle and create spots brighter than the planets themselves. The flower-like shape avoids this while blocking out the starlight – making a planet that is one ten billionth as bright as its host star visible.

The star shade and the telescope have to be aligned perfectly at 125,000 miles away. Once aligned, the system will observe a distant star, and then move to another distant star and re-align. This is technologically speaking, unchartered territory.

While this mission may not occur in full tomorrow, or even years from tomorrow, astronomers’ synapses are firing. We’re coming up with new techniques that will advance technology and find earth-like worlds.

Etc.

Above is a list of only a handful of future exoplanet missions – all at various stages in their production – with some still on the drawing board and others having received full funding and preparing for launch. With creativity and advancing technology we’ll detect a true-earth analogue in the near future.

Meanwhile, outside NASA…

ESA approved the Cheops mission (S-class) that will characterize known systems, including radial-velocity planets by detecting very small transits and/or phases of the orbiting planets.

Two M-class proposals are still in the race for the last slot due in 2022-24. EChO will try to observe exoplanet atmospheres with space-based spectroscopy. Plato will search for transiting planets with 32, partially overlapping telescopes, outperforming both Kepler and TESS.

According to the PLATO web page there was supposed to be a decision in October.

Current ESA plan: “The selection of the M3

mission is planned to take place in February 2014, with one single

mission selected for implementation. Mission adoption is planned to take

place in 2015.”