OTTAWA, CANADA — A new Canadian satellite — should it launch — might carry a sort of magnetized force field on board to keep charged particles away from vital electronics.

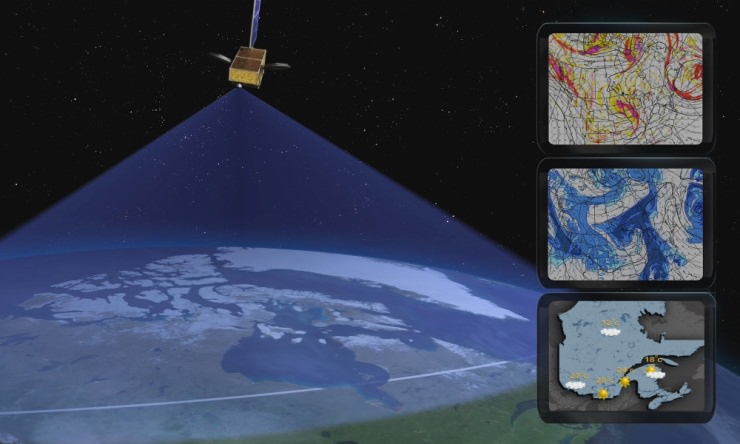

The Polar Communications and Weather Satellite (PCW), depending on its orbit, could skim through the radiation-filled Van Allen belts on its mission to deliver reliable weather reports and communications to northern communities.

Its polar orbit will likely take it through clouds of charged particles high above Earth. If the particles hit crucial components on the spacecraft, it can short out electronics and cause brownouts or complete failure. This has happened several times before, such as to the Japanese ADEOS-II satellite after a large solar storm in 2003.

A concept being explored by Winnipeg’s Magellan Aerospace, one of the companies working on the early phase studies, would make a plasma field around PCW, a sort of “mini magnetosphere” that would use large dipole magnets to deflect charged particles.

It may also be useful for human missions in the future, said Paul Harrison, a satellite control systems engineer at Magellan Aerospace, although he acknowledged the technology is still in an early stage and that they would like a demonstrator mission to fly first.

“It’s still very much in the development phase. We want to develop for satellites before we start sticking people in them,” Harrison said in a presentation at the Canadian Space Society annual summit in Ottawa, Canada, today (Nov. 14.)

He also said it is not clear if the technology would be useful for cosmic rays that originate from outside the solar system, as well as charged particles that flow from the sun and are present near the Earth.

PCW has not been assigned a launch date yet and is still in the early stages of development. Other issues being explored include how to keep track of it without constant access to near-equator-orbiting GPS satellites, and how to maintain temperature control as it plunges from day to night to day again during its journey.

Its orbit could be a 12-hour Molniya orbit or perhaps a 16-hour or 24-hour highly eccentric orbit, depending on what designers feel is best.

CORRECTION: This article has been changed to say “near-equator-orbiting” GPS satellites.

GPS satellites are not equator-orbiting. They orbit at a 55 degree inclination.

An interesting concept that’s been bandied about for years.. good to see someone actually doing something with it. What.. not pics? or engineering diagram?