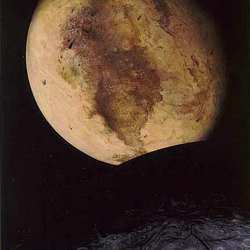

An artist’s conception of Pluto and its moon Charon. Image credit: NASA. Click to enlarge

On a clear summer night, the stars aligned for MIT researchers watching and waiting for one small light in the heavens to be extinguished, just briefly.

Thanks to a feat of both astronomical and terrestrial alignment, a group of scientists from MIT and Williams College succeeded in observing distant Pluto’s tiny moon, Charon, hide a star. Such an event had been seen only once before, by a single telescope 25 years ago, and then not nearly as well.

The MIT-Williams consortium spotted it with four telescopes in Chile on the night of July 10-11.

The team expects to use data from this observation to assess whether Charon has an atmosphere, to measure its radius and to determine how round it is.

The data and results from the observation will be presented at the 2005 meeting of the American Astronomical Society’s Division of Planetary Sciences meeting to be held in Cambridge, England, in September.

MIT team leader James L. Elliot headed the group at the Clay Telescope at Las Campanas Observatory in Chile.

“We have been waiting many years for this opportunity. Watching Charon approach the star and then snuff it out was spectacular,” said Elliot, a professor in the Department of Earth, Atmospheric and Planetary Science and the Department of Physics at MIT in Cambridge, Mass.

Jay M. Pasachoff, team leader from Williams College in Williamstown, Mass., and a professor in that school’s Department of Astronomy, said, “It’s amazing that people in our group could get in the right place at the right time to line up a tiny body 4 billion miles away. It’s quite a reward for so many people who worked so hard to arrange and integrate the equipment and to get the observations.”

With the Clay Telescope’s 6.5-meter mirror (more than 21 feet across, the size of a large room) the researchers were able to observe changes throughout the event, which lasted less than a minute. While their electronic cameras sensitively recorded data, the light of the faint star was seen to dim and then, some seconds later, brighten. This kind of disappearance of a celestial body behind a closer, apparently larger one is known as an occultation.

Studying how the light dimmed and brightened will let the MIT-Williams consortium look for signs that Charon has an atmosphere. It has very little mass and thus little gravity to hold in an atmosphere, but it is so cold (being some 40 times farther from the sun than the Earth) that some gases could be held in place by the small amount of Charon’s gravity.

Other telescopes around Chile used by the MIT-Williams consortium included the 8-meter (more than 26 feet across) Gemini South on Cerro Pachon, the 2.5-meter (more than 8 feet across) DuPont Telescope at Las Campanas Observatory and the 0.8-meter (almost 3 feet across) telescope at the Cerro Armazones Observatory of Chile’s Catholic University of the North near Cerro Paranal.

The team had searched for a distribution of telescopes along a north-south line in Chile since the predictions of the starlight shadow of Charon were uncertain by several hundred kilometers. Since the star that was hidden is so far away, it casts a shadow of Charon that is the same size as Charon itself, about 1,200 kilometers in diameter. To see the event, the distant star, Charon and the telescopes in Chile had to be perfectly aligned. All of these telescopes had clear views of the event.

Other MIT affiliates involved in the observation were MIT graduate students Elisabeth Adams, Michael Person and Susan Kern and postdoctoral associate Amanda Gulbis.

The images from three telescopes in Chile, including the Clay Telescope, and one in Brazil, were taken with new electronic cameras and computer control obtained by MIT and Williams with an equipment grant from NASA. The expeditions were sponsored by NASA’s Planetary Astronomy Program.

A video showing the star dimming as Charon passes in front of it and then brightening again is posted on the Web at http://occult.mit.edu/research/occultations/Charon/C313.2/C313OccMovie.html.

Teams from the Observatory of Paris at Meudon and from the Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, Colo., also observed the occultation.

Original Source: MIT News Release