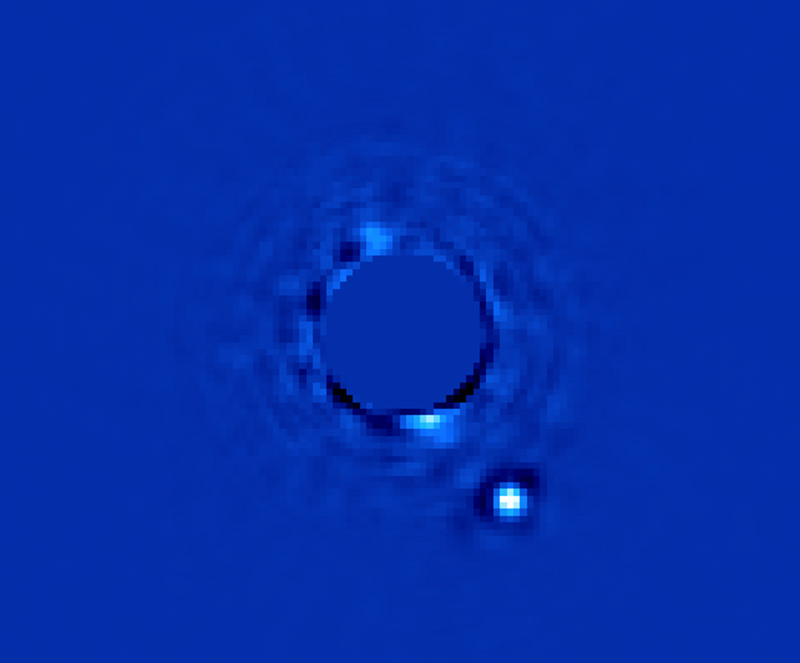

The world’s newest and most powerful exoplanet imaging instrument, the recently-installed Gemini Planet Imager (GPI) on the 8-meter Gemini South telescope, has captured its first-light infrared image of an exoplanet: Beta Pictoris b, which orbits the star Beta Pictoris, the second-brightest star in the southern constellation Pictor. The planet is pretty obvious in the image above as a bright clump of pixels just to the lower right of the star in the middle (which is physically covered by a small opaque disk to block glare.) But that cluster of pixels is really a distant planet 63 light-years away and several times more massive — as well as 60% larger — than Jupiter!

And this is only the beginning.

While many exoplanets have been discovered and confirmed over the past couple of decades using various techniques, very few have actually been directly imaged. It’s extremely difficult to resolve the faint glow of a planet’s reflected light from within the brilliant glare of its star — but GPI was designed to do just that.

“Most planets that we know about to date are only known because of indirect methods that tell us a planet is there, a bit about its orbit and mass, but not much else,” said Bruce Macintosh of the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, who led the team that built the instrument. “With GPI we directly image planets around stars – it’s a bit like being able to dissect the system and really dive into the planet’s atmospheric makeup and characteristics.”

And GPI doesn’t just image distant Jupiter-sized exoplanets; it images them quickly.

“Even these early first-light images are almost a factor of ten better than the previous generation of instruments,” said Macintosh. ” In one minute, we were seeing planets that used to take us an hour to detect.”

Despite its large size, Beta Pictoris b is a very young planet — estimated to be less than 10 million years old (the star itself is only about 12 million.) Its presence is a testament to the ability of large planets to form rapidly and soon around newly-formed stars.

Read more: Exoplanet Confirms Gas Giants Can Form Quickly

“Seeing a planet close to a star after just one minute, was a thrill, and we saw this on only the first week after the instrument was put on the telescope!” added Fredrik Rantakyro a Gemini staff scientist working on the instrument. “Imagine what it will be able to do once we tweak and completely tune its performance.”

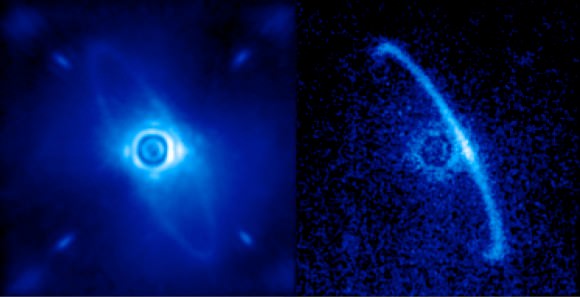

Another of GPI’s first-light images captured light scattered by a ring of dust that surrounds the young star HR4796A , about 237 light-years away:

The left image shows shows normal light, including both the dust ring and the residual light from the central star scattered by turbulence in Earth’s atmosphere. The right image shows only polarized light. Leftover starlight is unpolarized and hence removed. The light from the back edge of the disk (to the right of the star) is strongly polarized as it reflects towards Earth, and thus it appears brighter than the forward-facing edge.

It’s thought that the reflective ring could be from a belt of asteroids or comets orbiting HR4796A, and possibly shaped (or “shepherded,” like the rings of Saturn) by as-yet unseen planets. GPI’s advanced capabilities allowed for the full circumference of the ring to be imaged.

GPI’s success in imaging previously-known systems like Beta Pictoris and HR4796A can only indicate many more exciting exoplanet discoveries to come.

“The entire exoplanet community is excited for GPI to usher in a whole new era of planet finding,” says physicist and exoplanet expert Sara Seager of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. “Each exoplanet detection technique has its heyday. First it was the radial velocity technique (ground-based planet searches that started the whole field). Second it was the transit technique (namely Kepler). Now, it is the ‘direct imaging’ planet-finding technique’s turn to make waves.”

This year the GPI team will begin a large-scale survey, looking at 600 young stars to see what giant planets may be orbiting them.

“Some day, there will be an instrument that will look a lot like GPI, on a telescope in space. And the images and spectra that will come out of that instrument will show a little blue dot that is another Earth.”

– Bruce Macintosh, GPI team leader

The observations above were conducted last November during an “extremely trouble-free debut.” The Gemini South telescope is located near the summit of Cerro Pachon in central Chile, at an altitude of 2,722 meters.

Source: Gemini Observatory press release

I’m jumping up and down too! Champagne anyone? In a word.. WOW! That’s a HOT planet! How hot? Any integral field spectrograph data released yet?

Hi Aqua4U, I’m a member of the Gemini Planet Imager team. The images shown above were all taken with our integral field spectrograph. Very preliminary analyses of the spectrum of Beta Pic b suggest it’s about 1400-1500 K, but I’ll caution that’s an analysis literally a couple days old from results we obtained at the telescope just a few weeks ago, so the values may change by the time we do a more thorough analysis.

We’ll be releasing data to the community in mid February via the Gemini Observatory web site. Cheers, and thanks for your interest in our work!

Wow! Amazing images!

What an excellent instrument, the picture of the team says it all. Direct images of exoplanets will change public perception of the subject and probably theories of planetary formation too. I expect it is it too late to include one in the James Webb telescope, hopefully the Chinese will put one on the moon.

Wow, I can’t wait to see what else they find. I also hope they attempt to image some local systems, like Epsilon Eridani or Alpha Centauri.

Wow! And that ring is spectacular! I hope they will image the same planet multiple times and show us a GIF of an exoplanet orbiting its star!

Growing up as a kid, I never imagined we would be able to image such details from other solar systems. We may at some point be able to image Asteroid belt- and Kuiper belt-like objects around other stars, or confirm the existence of Oort cloud-like objects. This is a huge step. Congrats to everyone on the Gemini Planet Imager team. I will be having a dram of my very best single-malt in your honour tonight.

Impressive! Not that many years ago, the most powerful telescopes couldn’t even resolve the disk of a star, let alone see a planet around one. The advancement in imaging in the last few years is incredible.

I note that Silicon melts at 1414 °C and Iron at 1538 °C.

A Wiki link? http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Melting_points_of_the_elements_%28data_page%29

1400-1500 K is some 2060.33 – 2240.33 °F.. An interesting coincidence the temperature of lava on Earth ranges from 1,292 to 2,190 °F?

As a science fanatic and a believer in God, I find this to be extremely intellectually and spiritually satisfying. I’m thinking of this right now: http://www.lds.org/scriptures/pgp/moses/1.27-42#26 (BTW, I’m not a young earth creationist or any of that. I do believe the universe is at least as old as we’ve observed it to be, if not older due to the cosmic horizon effect. I just happen to believe it’s not accidental, and that there is a purpose to it all.)