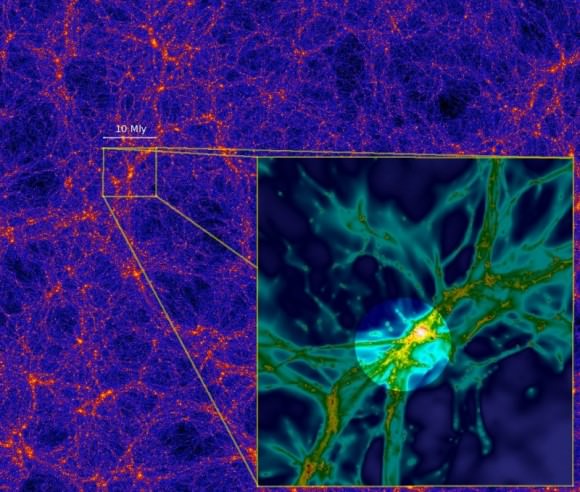

Funny how a single quasar can illuminate — literally and figuratively — some of the mysteries of the universe. From two million light-years away, astronomers spotted a quasar (likely a galaxy with a supermassive black hole in its center) shining on a nearby collection of gas or nebula. The result is likely showing off the filaments thought to connect galaxies in our universe, the team said.

“This is a very exceptional object: it’s huge, at least twice as large as any nebula detected before, and it extends well beyond the galactic environment of the quasar,” stated Sebastiano Cantalupo, a postdoctoral fellow at the University of California Santa Cruz who led the research.

The find illuminated by quasar UM287 could reveal more about how galaxies are connected with the rest of the “cosmic web” of matter, astronomers said. While these filaments were predicted in cosmological simulations, this is the first time they’ve been spotted in a telescope.

“Gravity causes ordinary matter to follow the distribution of dark matter, so filaments of diffuse, ionized gas are expected to trace a pattern similar to that seen in dark matter simulations,” UCSC stated.

Astronomers added that it was lucky that the quasar happened to be shining in the right direction to illuminate the gas, acting as a sort of “cosmic flashlight” that could show us more of the underlying matter. UM287 is making the gas glow in a similar way that fluorescent light bulbs behave on Earth, the team added.

“This quasar is illuminating diffuse gas on scales well beyond any we’ve seen before, giving us the first picture of extended gas between galaxies,” stated J. Xavier Prochaska, coauthor and professor of astronomy and astrophysics at UC Santa Cruz. “It provides a terrific insight into the overall structure of our universe.”

The find was made using the 10-meter Keck I telescope at the W. M. Keck Observatory in Hawaii. You can check out more details on the discovery on the Keck Observatory’s website or at this press release from the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy in Heidelberg, Germany.

The research was published in the Jan. 19 edition of Nature and available in preprint version on Arxiv.

Er… that should be 10 billion light-years away, not “two million”.