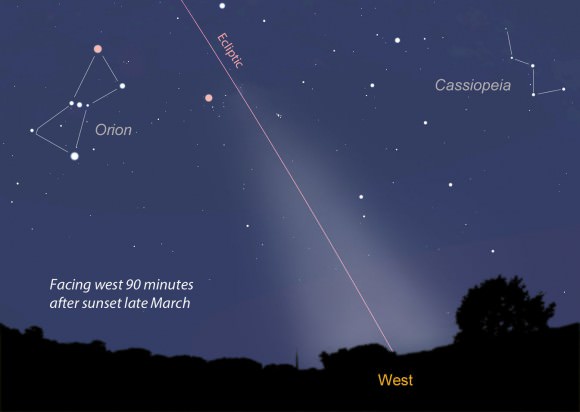

Welcome to the first day of spring! If you have a clear night between now and April 1, celebrate the new season with a pilgrimage to the countryside to ponder the eerie glow of the zodiacal light. Look for a large, diffuse, tapering cone of light poking up from the western horizon between 90 minutes and two hours after sunset. While the zodiacal light appears only as bright as the Milky Way, you’re actually looking at the second brightest object in the night sky. No kidding. If you could crunch it all into a little ball, it would shine at magnitude -8.5, far brighter than Venus and bested only by the full moon.

Sunlight reflecting off countless dust particles shed by comets and spawned by asteroid collisions creates the luminous cone of light. First time observers might think they’re looking at skyglow from light pollution but the tapering shape and distinctive tilt mark this glow as interplanetary dust.

Like the planets, the dust resides in the plane of the solar system. In spring, that plane (called the ecliptic) tilts steeply up from the western horizon after sunset, “lifting” the chubby thumb of light high enough to clear the horizon haze and stand out against a dark sky for northern hemisphere observers. In October and November the ecliptic is once again tilted upright, but this time before dawn. While the zodiacal light is present year-round, it’s usually tipped at a shallow angle and camouflaged by horizon haze. No so for skywatchers in tropical and equatorial latitudes. There the ecliptic is tilted steeply all year long, and the light can be seen anytime there’s no moon in the sky.

Now through April 1 and again from April 17-30 are the best nights for viewing because the moon will be absent from the sky. The cone is widest near the western horizon and narrows as you direct your gaze upward and to the left. At its apex, where it touches the V-shape Hyades star cluster, it continues into the even fainter zodiacal band and gegenschein, but more about that in a moment. Sweep your gaze in broad strokes back and forth across the western sky to help you discern the Z-light’s distinctive conical shape. And be sure to look for something HUGE. This thing is a monster – indeed, one of the largest entities in the solar system.

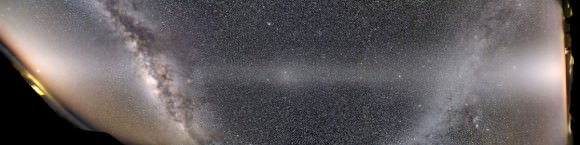

Observers fortunate enough to live under or with access truly dark skies can trace the zodiacal light all the way across the sky as the zodiacal band.

Midway along its length, 180 degrees opposite the sun, a slightly brighter circular patch called the gegenschein (German for ‘counter glow’) embedded in the band.

Dust particles there get an extra brightness boost because they face the sun square on, much like the moon does when full. While I usually see only a section of the zodiacal band from my dark observing site, the gegenschein is often visible as a diffuse, hazy patch of light about 6 degree across a little brighter than the sky background.

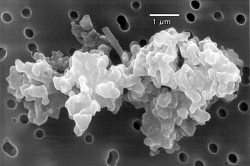

Dutch astronomer H. C. van de Hulst determined that the dust particles responsible for the zodiacal light and its cousins the zodiacal band and gegenschein are about 0.04 inch (1 mm) in diameter and separated, on average, by about 5 miles (8 km).

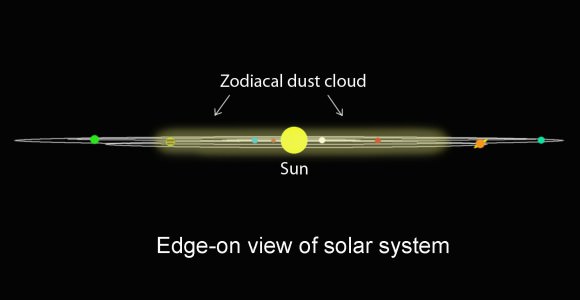

The particles form a low density, lens-shaped cloud of dust that’s thickest within the plane of the solar system but in reality covers the entire sky but ever so thinly. Sunlight absorbed by the particles is re-emitted as invisible infrared (heat) radiation. This re-radiation robs the dust of energy, causing the particles to spiral slowly into the sun. Fresh dust from the vaporization of cometary ices as well as collisions of asteroids replenishes the cloud.

According to a study by Joseph Hahn and colleagues of the Clementine Mission data, comet dust accounts for the majority of the zodiacal dust within 1 a.u. (93 million miles) of the sun; a mix of asteroidal and comet dust makes up the remainder.

Stepping out on a spring evening to look at the zodiacal light, we can appreciate how small things can come together to create something grand.