The latest observations by the Keck Observatory in Hawaii show that the gas cloud called “G2” was surprisingly still intact, even during its closest approach to the supermassive black hole at the center of our Milky Way galaxy. Astronomers from the UCLA Galactic Center Group reported today that observations obtained on March 19 and 20, 2014 show the object’s density was still “robust” enough to be detected. This means G2 is not just a gas cloud, but likely has a star inside.

“We conclude that G2, which is currently experiencing its closest approach, is still intact,” said the group in an Astronomer’s Telegram, “in contrast to predictions for a simple gas cloud hypothesis and therefore most likely hosts a central star. Keck LGSAO observations of G2 will continue in the coming months to monitor how this unusual object evolves as it emerges from periapse passage.”

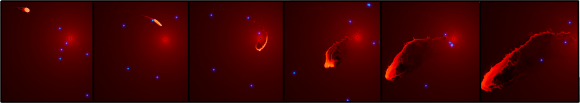

We’ve been reporting on this object since its discovery was announced in 2012. G2 was first spotted in 2011 and was quickly deemed to be heading towards our galaxy’s supermassive black hole, called Sgr A*. G2 is not falling directly into the black hole, but it will pass Sgr A* at about 100 times the distance between Earth and the Sun. But that was close enough that astronomers predicted that G2 was likely doomed for destruction.

But it appears to still be hanging in there, at least in mid-March 2014.

Earlier this week, we explained how there were two ideas of what G2 is: one is a simple gas cloud, and the second opinion is that it is a star surrounded by gas. Some astronomers argue that they aren’t seeing the amount of stretching or “spaghettification” that would be expected if this was just a cloud of gas.

The latest word seems to confirm that G2 is more than just a cloud of gas.

This is exciting for astronomers, since they usually don’t get to see events like this take place “in real time.” In astrophysics, timescales of events taking place are usually very long — not over the course of several months. But it’s important to note that G2 actually met its demise around 25,000 years ago. Because of the amount of time it takes light to travel, we can only now observe this event which happened long ago.

We’ll keep you posted on any future news and observations.

Well, as xkcd.com brilliantly explains, relativity saves the day, since for the photon no time has passed. On the other hand, this also demonstrates that the notion “it has happened a long time ago” is not as straight forward as it seems. And since we are looking at it “now” from our perspective, it is fair enough to say that G2 hits Sgr A* right now.

I hope we still get some activity from it, that is activity from Sgr A* when it feeds on G2. If Gs is, however, a star covered in a bit of a cloud, then probably the star will pass by mostly unharmed and only very little of the gas may actually reach the event horizon. That’s actually a bummer. I hoped for some accretion activity. Since we can’t observe accretion processes in close proximity, this might have been our best chance so far with all telescopes pointed at it. Maybe the star is captured and devoured slowly. But that seems unlikely.

Have there been any other stars observed so far, which approached Sgr A* as close as 100 AU? I’ve seen an animation of the closest stars orbiting Sgr A*, and one star in particular reached a very high velocity at the periapse. So, I’m just wondering how fast G2 would move at the periapse if it doesn’t get spagettified first. I didn’t quite understand from the article if it has already passed periapse or not…? (“…even during its closest approach…” could be “closest approach YET” or “closest approach ever”=periapse).