Here’s a finding to give planetary protectionists pause: two species of spores mounted on the International Space Station’s hull a few years back showed a high survival rate after 18 months in space.

Providing that they are shielded against solar radiation, it appears the spores are quite hardy and could easily transport on a spacecraft headed for Mars — which is concerning since so many scientific investigations there these days are focused on habitability of Martian life (whether past or present). The experiment was published in 2012, but highlighted in a recent NASA press release about planetary protection.

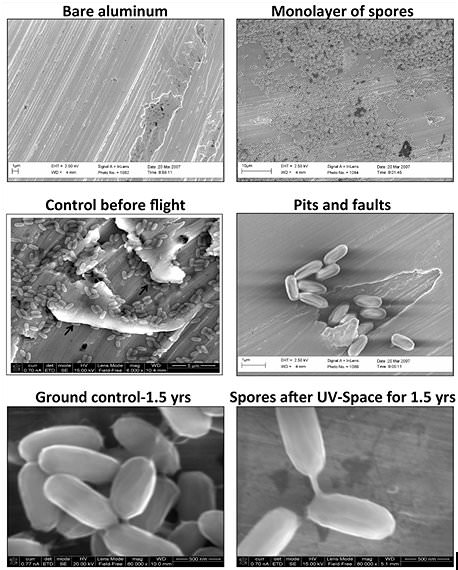

The experiment was called PROTECT (an acronym of Resistance of spacecraft isolates to outer space for planetary protection purposes) and studied spores of Bacillus subtilis 168 and Bacillus pumilus SAFR-032. B. pumilus spores were found in an air lock between a “clean room” and entrance floor at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, and in previous studies were shown to be more resistant to UV radiation and hydrogen peroxide than “wild” strains. B. subtilis is a spore that has been studied in other space environment experiments.

Samples of both spores were mounted on the EXPOSE-E facility on the space station, which provides up to two years of space exposure. The major goal of this European Space Agency experiment is to study “the origin, evolution and distribution of life in the universe,” NASA states, adding that anything mounted outside of there has to survive “cosmic radiation, vacuum, full-spectrum solar light including UV-C, freezing/thawing cycles [and] microgravity.”

The experiment found that if the spores were in areas replete with solar UV radiation, most of them were killed. If those rays were filtered out, however, the spores showed a 50 percent survival rate on both space and simulated “Mars” conditions. It is most concerning to scientists when considering a situation where spores could be hiding underneath each other during a spacecraft trip. The ones on the outside would likely die, but the ones on the inside — shielded from solar radiation — could make it there.

One key limitation in this study, however, is that only two types of spores were studied. This does present a case for doing more studies on this matter in the future, however. Space agencies are quite aware of the problem of planetary protection, as evidenced by departments such as NASA’s Office of Planetary Protection and ESA’s Planetary Protection Officer.

Spacecraft designers constantly make decisions to keep the extraterrestrial bodies we study as safe from Earth contamination as possible; one famous example was when the Galileo probe was deliberately sent into Jupiter in 2003 to protect Europa and other potentially life-bearing moons of the giant planet from possible contamination.

You can read the entire study (led by DLR’s Gerda Horneck) in Astrobiology. Also note that there are two other EXPOSE-E studies published around the same time: “Survival of Rock-Colonizing Organisms After 1.5 Years in Outer Space” and “Survival of Bacillus pumilus Spores for a Prolonged Period of Time in Real Space Conditions.”

The rock study (led by Tuscia University’s Silvano Onofri) takes the question of the spores in a different direction, which is examining the phenomenon of “lithopanspermia” — how organisms might move between planets (say, on a meteor). Since Mars meteorites have been found on Earth, some researchers have wondered if life could have spread between our two planets. If that were to happen, the researchers cautioned, the spores would have to survive for thousands or millions of years.

The other B. pumilus paper (led by NASA’s Parag A. Vaishampayan) noted that those spores mounted outside of the space station that survived, showed higher concentrations of proteins that could be linked to resisting UV radiation.

The point of space exploration is settlement not science. Science is a nice to have. Given that, it would be impossible for a human settlement to exist on Mars without massive contamination with earth microbial life. So what? We are going to turn it into a human world if at all possible.

The “point” is to discover whether there are any Martian lifeforms before we contaminate the planet. If there are, we may have to consider the harm we (and our bacterial cousins) pose to them before colonizing the place.

Or leave it to be a sterile science outpost. A permanent human population in cans and mobile habs and suits, but carefully controlled to minimize contamination until we have some ide4a of ways to tell whether we’re sampling something actually from Mars or something from a previous explorer’s digestive tract.

In the meantime, colonize space. Why drop down onto another cold dark hole on a rock? Space has resources, low or no G (also useful if you want to create full Earth G, which you couldn’t do on Mars).

What good is Mars? At present total surface area equal to the land area of Earth. “Terraform” it, if possible, and you get less than a quarter of that.

Just the inner Belt and NEAs and short period comets have resources for living space tens of thousands of times greater, in better living conditions.

Until we know EVERYTHING about what Mars is and has been can teach us, it’s reckle3sslty irresponsible to science and to future human life (which “terraform now” advocates claim they’re serving) to destroy Mars as it is.

Do you KNOW for certain that there’s life on Mars? Do you know for certain if there’s not? How many man-centuries of boots-on-the-ground will it take to know for certain that it’s told us everything?

Mars is simply not needed for human habitation. Not for a second branch of civilization, not for more room for Earth’s teeming billions to expand to, not for a few wandering outcasts to pioneer and try out their new way of life.