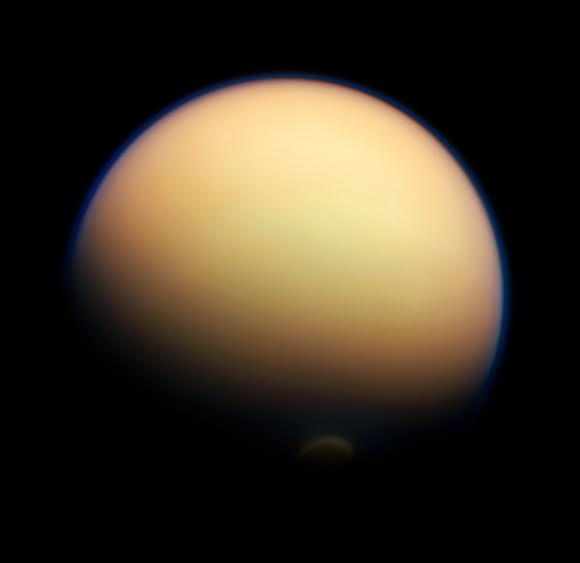

Titan — that smoggy, orangy moon circling Saturn — is of great interest to exobiologists because its chemistry could be good for life. It has a thick atmosphere of nitrogen and methane and likely has lakes filled with liquid hydrocarbons, and scientists believe there is enough light filtering down into the atmosphere to drive chemical reactions.

It turns out the moon could also be a good analog to help us understand the atmospheres of exoplanets far beyond our solar system. From looking at sunsets on the moon, scientists led by NASA believe that a thick atmosphere could influence how we perceive a planet from afar.

First, a bit of information about how scientists learn about planet atmospheres in the first place. When a distant planet passes in front of its parent star, the light from the star passes through the atmosphere and gets distorted.

The spectra that telescopes pick up can then tell scientists information about what the atmosphere is made of, what temperature it is, and how it is structured. (This science, it should be noted, is in its very early stages and works best on very large exoplanets that are relatively close to Earth, since the planets are so small and far away.)

“Previously, it was unclear exactly how hazes were affecting observations of transiting exoplanets,” stated Tyler Robinson, a postdoctoral research fellow at NASA’s Ames Research Center who led the research. “So we turned to Titan, a hazy world in our own solar system that has been extensively studied by Cassini.”

To do this, Robinson’s team used data from the Cassini spacecraft during four solar occultations, or times when Titan passed in front of our own sun from the perspective of the spacecraft. They found out that the moon’s hazy atmosphere makes it difficult to figure out what is in its spectra.

“The observations might be able to glean information only from a planet’s upper atmosphere,” NASA stated. “On Titan, that corresponds to about 90 to 190 miles (150 to 300 kilometers) above the moon’s surface, high above the bulk of its dense and complex atmosphere.”

The haze is even more powerful in the shorter (bluer) wavelengths of light, which contradicts previous studies assuming that all wavelengths of light would have the same distortions. Models of exoplanet atmospheres usually have simplified spectra because hazes are complex to model, requiring a lot of computer power.

Researchers hope to take these observations of Titan and then use them to better inform how exoplanet models are created.

The research was published May 26 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Science.

Source: NASA

Just goes to show how wrong assumptions can be. Are they using the Rossiter-McGlauchlin effect to see the distortion at different wavelengths?