Since 1995, astronomers have detected thousands of worlds orbiting nearby stars, sparking a race to find the one that most resembles Earth. The discovery of habitable exoplanets and even extraterrestrial life is often referred to as the Holy Grail of science. So with the gold rush of exoplanet discoveries these days, it’s pretty tempting in news articles to lose readers in a fantastical narrative.

This month I’m launching a project on Beacon — a new independent platform for journalism — that will go behind the sensational headlines covering the search for Earth 2.0.

But I can’t do it without your help. In order to commit to writing about this on a regular basis, I need to raise $4,000 from subscribers who are willing to support my work over this month. Don’t worry, subscriptions are available for only $5 per month. This will supply the funding necessary to write for six months.

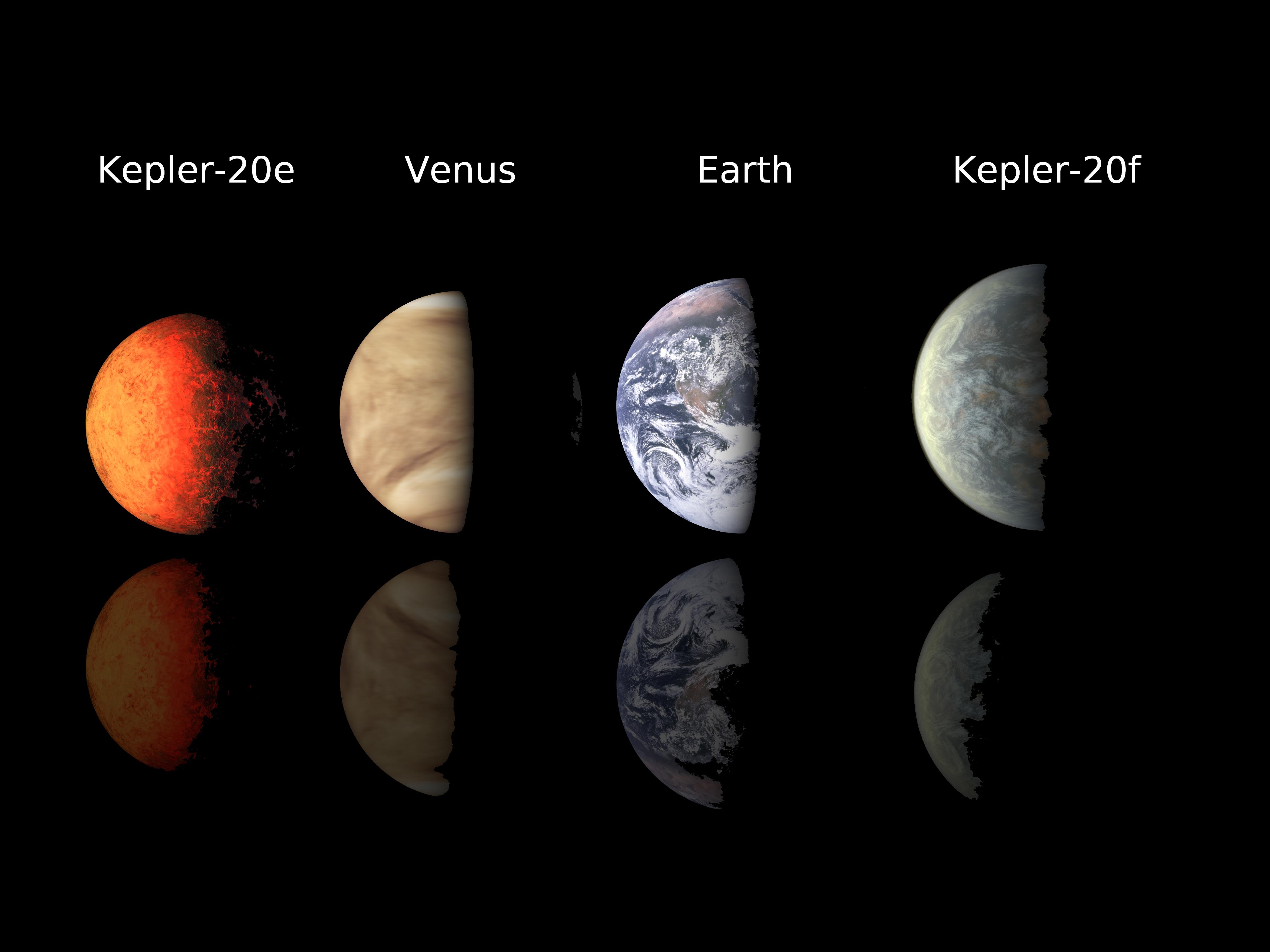

By Kepler’s definition, to be Earth-like a planet must be both Earth-size (less than 1.25 times Earth’s radius and less than twice Earth’s mass) and must circle its host star within the habitable zone: the band where liquid water can exist.

This simple, and yet variant, definition is a crucial starting point. But one glance at our Solar System (namely Venus and Mars) demonstrates that just because a planet is Earth-like doesn’t mean it’s an Earth twin.

So even if we do find Earth-like planets, we still don’t have the ability to know if they’re water worlds with luscious green planets and civilizations peering back at us.

But should we scale our definition of Earth-like planets up or down? Examples in the Solar System suggest that we should scale it down. Maybe planets located nearer to the center of the habitable zone are more congenial to life.

But can we base our definition on a single example — even if it’s the only example we know — alone? Theoretical astronomers suggest the picture is much more complicated. Life might arise on larger worlds, ones up to three times as massive as Earth, because they’re more likely to have an atmosphere due to more volcanic activity. Or life might arise on older worlds, where there’s simply more time for life to evolve.

It’s a crucial debate in astronomy research today, and it’s one that the media needs to handle with care. I am proud to be a part of Universe Today’s team, bringing readers up-to-date with the on goings in our local Universe. And Beacon will allow me to spend even more time, focusing on such a critical topic.

For each article, I will gather news, opinions and commentary from astronomers in the field. Not only do I have training as an astronomer, but my graduate school research focused on detecting exoplanet atmospheres from ground-based telescopes. With this deep-rooted understanding of the field at hand, I am able to parse complex information by directly reading peer-reviewed journal articles and interviewing astronomers I’ve met through my previous research.

But I really do need your help. Subscriptions are available for only $5 per month, and there are special rewards — such as gorgeous astronomy photos printed on canvas and gift subscriptions for friends — for people who subscribe at higher levels. You can directly subscribe here.

But here’s the best part: when you subscribe to my work, you’ll get access not only to all the stories I write, but the work of over 100 additional writers, based all over the world. This month Beacon is launching a series of astronomy projects, including one by Universe Today writer Elizabeth Howell.

Please help me write about our exciting search for Earth-like planets.

Good luck Shannon…

It seems a good project.