The paths of total solar eclipses care not for political borders or conflicts, often crossing over war-torn lands.

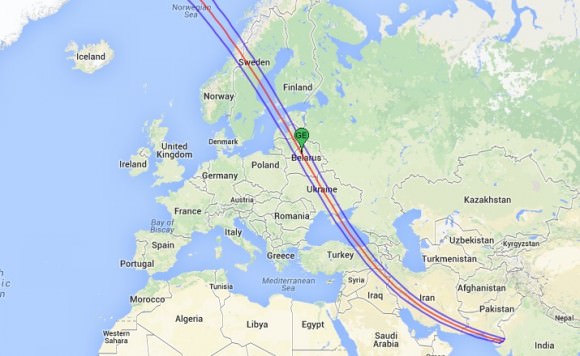

Such was the case a century ago this week on August 21st, 1914 when a total solar eclipse crossed over Eastern Europe shortly after the outbreak of World War I.

Known as the “War to End All Wars,” — which, of course, it didn’t — World War I would introduce humanity to the horrors of modern warfare, including the introduction of armored tanks, aerial bombing and poison gas. And then there was the terror of trench warfare, with Allied and Central Powers slugging it out for years with little gain.

But ironically, the same early 20th century science that was hard at work producing mustard gas and a better machine gun was also pushing back the bounds of astronomy. Einstein’s Annus Mirabilis or “miracle year” occurred less than a decade earlier on 1905. And just a decade later in 1924, Edwin Hubble would expand our universe a million-fold with the revelation that “spiral nebulae” were in fact, island universes or galaxies in their own right.

Indeed, it’s tough to imagine that many of these discoveries are less than a century in our past. It was against this backdrop that the total solar eclipse of August 21st, 1914 crossed the eastern European front embroiled in conflict.

Solar eclipses have graced the field of battle before. An annular solar eclipse occurred during the Battle of Isandlwana in 1879 during the Zulu Wars, and a total solar eclipse in 585 B.C. during the Battle of Thales actually stopped the fighting between the Lydians and the Medes.

But unfortunately, no celestial spectacle, however grand, would save Europe from the conflagration war. In fact, several British eclipse expeditions were already en route to parts of Russia, the Baltic, and Crimea when the war broke out less than two months prior to the eclipse with the assassination of Archduke Ferdinand on June 28th, 1914. Teams arrived to a Russia already mobilized for war, and Britain followed suit on August 4th, 1914 and entered the war when Germany invaded Belgium.

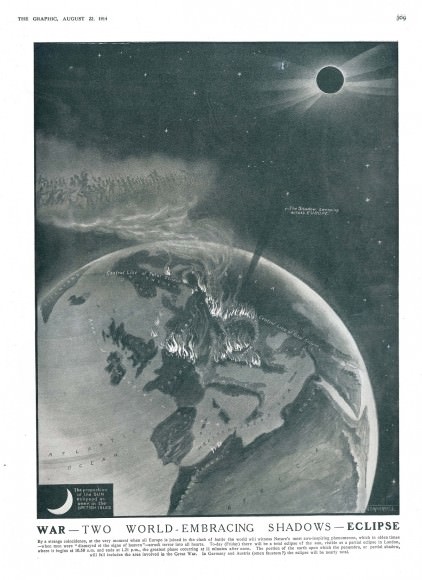

You can see an ominous depiction of the path of totality from a newspaper of the day, provided from the collection of Michael Zeiler:

Note that the graphic depicts a Europe aflame and adds in the foreboding description of Omen faustum, inferring that the eclipse might be an “auspicious omen…” eclipses have never shaken their superstitious trappings in the eyes of man, which persists even with today’s fears of a “Blood Moon.”

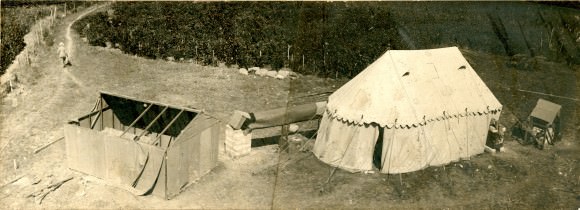

A race was also afoot against the wartime backdrop to get an expedition to a solar eclipse to prove or disprove Einstein’s newly minted theory of general relativity. One testable prediction of this theory is that gravity bends light, and astronomers soon realized that the best time to catch this in action would be to measure the position of a star near the limb of the Sun — the most massive light bending object in our solar system — during a total solar eclipse. The advent of World War I would scrub attempts to observe this effect during the 1914 and 1916 eclipses over Europe.

An expedition led by astronomer Arthur Eddington to observe an eclipse from the island of Principe off of the western coast of Africa in 1919 declared success in observing this tiny deflection, measuring in less than two seconds of arc. And it was thus that a British expedition vindicated a German physicist in the aftermath of the most destructive war up to that date.

The total solar eclipse of August 21st 1914 was a member of saros cycle 124, and was eclipse number 49 of 73 in that particular series. Eclipses in the same saros come back around to nearly the same circumstances once every triple saros period of 3 times 18 years and 11.3 days, or about every 54+ years, and there was an eclipse with similar circumstances slightly east of the 1914 eclipse in 1968 — the last total eclipse of saros 124 — and a partial eclipse from the same saros will occur again on October 25th, 2022.

All historical evidence we’ve been able to track down suggests that observers that did make it into the path of totality were clouded out at show time, or at very least, no images of the August 21st 1914 eclipse exist today. Can any astute reader prove us wrong? We’d love to see some images of this historical eclipse unearthed!

And, as with all things eclipse related, the biggest question is always: when’s the next one? Well, we’ve got another of total lunar eclipse coming right up on October 8th, 2014, again favoring North America. The next total solar eclipse occurs on March 20th, 2015 but is only visible along a path covering the Faroe and Svalbard Islands, with a path crossing the Norwegian Sea.

But, by happy coincidence, we’re also only now three years out this week from the total solar eclipse of August 21st, 2017 that spans the contiguous “Lower 48” of the United States. The shadow of the Moon will race from the northwest and make landfall off of the Pacific coast of Oregon before reaching a maximum duration for totality at 2 minutes and 40 seconds across Missouri, southern Illinois and Kentucky and will then head towards the southeastern U.S. to depart land off of the coast of South Carolina. Millions will witness this event, and it will be the first total solar eclipse for many. A total solar eclipse hasn’t crossed the contiguous United States since 1979, so you could say that we’re “due”!

Already, towns in Kentucky to Nebraska have laid plans to host this event. The eclipse occurs towards the afternoon for residents of the eastern U.S., which typically sees afternoon thunderstorms popping up in the sultry August summer heat. Eclipse cartographer Michael Zeiler states that the best strategy for eclipse chasers three years hence is to “go west, young man…”

It’s fascinating to ponder tales of eclipses past, present, and future and the role that they play in human history… where will you be on August 21st, 2017?

– Check out Michael Zeiler’s new site, GreatAmericanEclipse.com

– Eclipses pop up in science fiction on occasion as well… check out our history spanning eclipse tale Exeligmos.

Great story. Comets and Solar Eclipses have been harbingers of ominous or sometimes glorious events ever since humans have looked up and wondered.

I missed the 1979 eclipse while in Idaho due to overcast and I’d completely agree that “go west” is a near must to avoid missing a practically once in a lifetime event due to clouds. Only once in one’s lifetime will you be able to step outside your home and look up or get in one’s car and drive to a total solar eclipse.

As for the 1917 Total in the USA, one thing that is pointed out is that totality does not pass through any large US city. So there will be a lot of people heading for the hills, so to speak, getting out of town to see it. They say the interstates and small towns in the western states will be busy.

While General Relativity was published in 1916, Einstein predicted the bending of light by gravity in 1911. I think this was part of the challenges he laid out at the Solvay conference in Prague of that year. Weather got the best of the 1914 and I think the war was the real obstruction for the 1916 Total so it was finally the 1919 and Eddington that confirmed the deflection of light by gravity. There were a couple of false-negatives in 1917 by Mt. Wilson and Lick astronomers.

“Only once in one’s lifetime will you be able to step outside your home and look up or get in one’s car and drive to a total solar eclipse.”

That’s untrue. We had a total eclipse where I live when I was in 4th grade and about 20 years later we will be in the ~95% zone for the 2017 eclipse and only about a 5-6 hour drive would get me to the path of the totality.

Maybe its twice in a lifetime but its Fred Espenak that could clear this up. Probably an average of 1.5 or lets put within 2 days drive as a constraint. Or lets split a hair put it up to the Moon and see a diffraction pattern. 🙂

Looks like I’ve had my “once in a lifetime” experience then! I live in Cairns, Australia, and when we had the total eclipse pass through in 2012 I decided to go on a dedicated eclipse cruise to the outer great barrier reef to view it (about a 45min ride).

Absolutely glad I did, as I and about 50 or so others had absolute unrestricted front row seats of the full eclipse, whereas I believe most that were on land were clouded out for most of it! Was absolutely surreal 🙂

Thanks. I wondered the same thing about whether Einstein had posited the bending of light by gravity prior to the 1914 eclipse while researching the piece and came up with the 1911 date as well.

The 2017 eclipse is the next in the Saros 145 series. This is significant to me because I witnessed (sort of) the last one in August 1999, and my mother remembered a previous one from the same Saros in 1927. Those were the last two total eclipses visible from the UK.

In 1999 the track of totality passed only across the extreme south west corner of the UK, so to improve my chances I took the ferry to France, which I thought would be better in terms of avoiding the huge amount of traffic funneling into a small area, more chance of finding clear skies, and not least a chance to stock up with some cheap food and wine.

However, although the cloud was thin enough to be able to see as the Sun tantalisingly grew smaller and smaller, totality and the corona was completely invisible.

My pain was complete when some old schoolfriends later told me they had gone to Cornwall and found one of the few spots where the clouds parted just in time, and had a great view!

I may just manage to make that trip across the Atlantic to catch this one.

Every time the subject of eclipses is raised I learn something new. I just discovered the idea of semester series, relating all eclipses in a 4 year period, in this case 20 March 2015 – 11 August 2018.