Fabrication of the pathfinding version of NASA’s Orion crew capsule slated for its inaugural unmanned test flight in December is entering its final stages at the Kennedy Space Center (KSC) launch site in Florida.

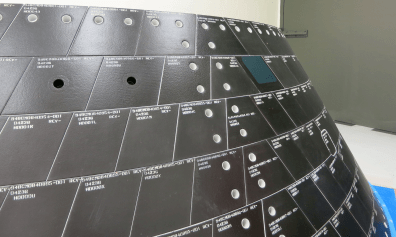

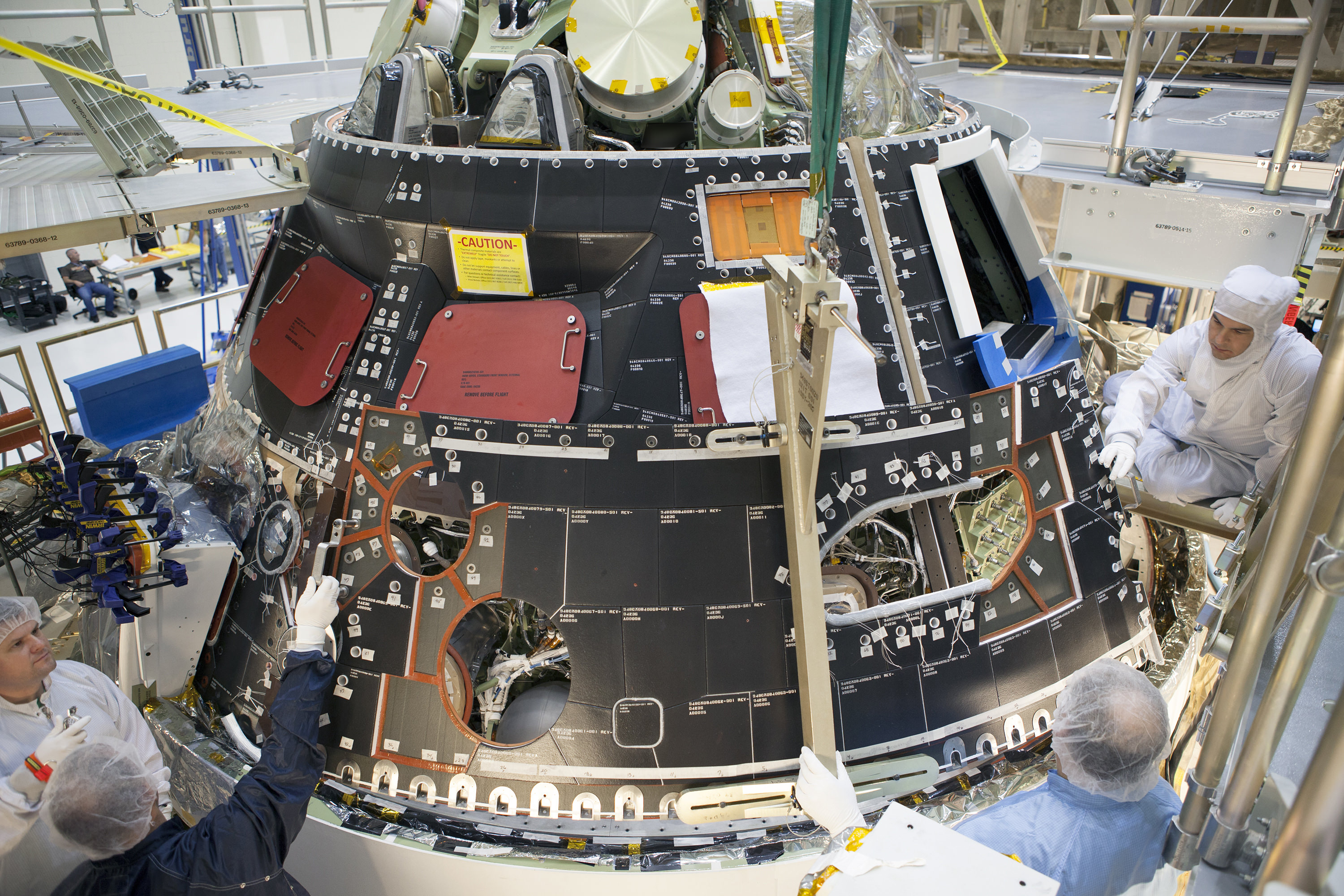

Engineers and technicians have completed the installation of Orion’s back shell panels which will protect the spacecraft and future astronauts from the searing heat of reentry and scorching temperatures exceeding 3,150 degrees Fahrenheit.

Orion is scheduled to launch on its maiden uncrewed mission dubbed Exploration Flight Test-1 (EFT-1) test flight in December 2014 atop the mammoth, triple barreled United Launch Alliance (ULA) Delta IV Heavy rocket from Cape Canaveral, Florida.

The cone-shaped back shell actually has a rather familiar look since its comprised of 970 black thermal protection tiles – the same tiles which protected the belly of the space shuttles during three decades and 135 missions of returning from space.

However, Orion’s back shell tiles will experience temperatures far in excess of those from the shuttle era. Whereas the space shuttles traveled at 17,000 miles per hour, Orion will hit the Earth’s atmosphere at some 20,000 miles per hour on this first flight test.

The faster a spacecraft travels through Earth’s atmosphere, the more heat it generates. So even though the hottest the space shuttle tiles got was about 2,300 degrees Fahrenheit, the Orion back shell could get up to 3,150 degrees, despite being in a cooler area of the vehicle.

Engineers have also rigged Orion to conduct a special in flight test to see just how vulnerable the vehicle is to the onslaught of micrometeoroid orbital debris.

Even tiny particles can cause immense and potentially fatal damage at high speed by punching a hole through the back shell tiles and possibly exposing the spacecrafts structure to temperatures high than normal.

“Below the tiles, the vehicle’s structure doesn’t often get hotter than about 300 degrees Fahrenheit, but if debris breeched the tile, the heat surrounding the vehicle during reentry could creep into the hole it created, possibly damaging the vehicle,” says NASA.

The team has run done numerous modeling studies on the effect of micrometeoroid hits. Now it’s time for a real world test.

Therefore engineers have purposely drilled a pair of skinny 1 inch wide holes into two 1.47 inches thick tiles to mimic damage from a micrometeoroid hit. The holes are 1.4 inches and 1 inch deep and are located on the opposite side of the back shell from Orion’s windows and reaction control system jets, according to NASA.

“We want to know how much of the hot gas gets into the bottom of those cavities,” said Joseph Olejniczak, manager of Orion aerosciences, in a NASA statement.

“We have models that estimate how hot it will get to make sure it’s safe to fly, but with the data we’ll gather from these tiles actually coming back through Earth’s atmosphere, we’ll make new models with higher accuracy.”

The data gathered will help inform the team about the heat effects from potential damage and possible astronaut repair options in space.

Orion is NASA’s next generation human rated vehicle now under development to replace the now retired space shuttle.

The state-of-the-art spacecraft will carry America’s astronauts on voyages venturing farther into deep space than ever before – past the Moon to Asteroids, Mars and Beyond!

The two-orbit, four and a half hour EFT-1 flight will lift the Orion spacecraft and its attached second stage to an orbital altitude of 3,600 miles, about 15 times higher than the International Space Station (ISS) – and farther than any human spacecraft has journeyed in 40 years.

The EFT-1 mission will test the systems critical for future human missions to deep space.

Orion’s back shell attachment and final assembly is taking place in the newly renamed Neil Armstrong Operations and Checkout Building, by prime contractor Lockheed Martin.

One of the primary goals of NASA’s eagerly anticipated Orion EFT-1 uncrewed test flight is to test the efficacy of the heat shield and back shell tiles in protecting the vehicle – and future human astronauts – from excruciating temperatures reaching over 4000 degrees Fahrenheit (2200 C) during scorching re-entry heating.

At the conclusion of the EFT-1 flight, the detached Orion capsule plunges back and re-enters the Earth’s atmosphere at 20,000 MPH (32,000 kilometers per hour).

“That’s about 80% of the reentry speed experienced by the Apollo capsule after returning from the Apollo moon landing missions,” Scott Wilson, NASA’s Orion Manager of Production Operations at KSC, told me during an interview at KSC.

A trio of parachutes will then unfurl to slow Orion down for a splashdown in the Pacific Ocean.

The Orion EFT-1 vehicle is due to roll out of the O & C in about two weeks and be moved to its fueling facility at KSC for the next step in launch processing.

Orion will eventually launch atop the SLS, NASA’s new mammoth heavy lift booster which the agency is now targeting for its maiden launch no later than November 2018 – detailed in my story here.

Stay tuned here for Ken’s continuing Orion, SLS, Boeing, Sierra Nevada, Orbital Sciences, SpaceX, commercial space, Curiosity, Mars rover, MAVEN, MOM and more Earth and planetary science and human spaceflight news.

What happens to the second stage? Does it remain in the 3600 mile altitude orbit? Once we lift it to orbit, it seems wasteful to let it burn up, especially if it might come in useful as future building materials.

Sweet! Now where’s that new lunar lander? Will any new lander be tested in LEO like the LEM was during Apollo 9? Can the second stage be taken along to the moon and used to explore polar craters via impact? Any ‘return to the moon’ mission plans for this vehicle out yet?

This is how the Americans experienced when they saw the Apollo being built.

We live in interesting times.