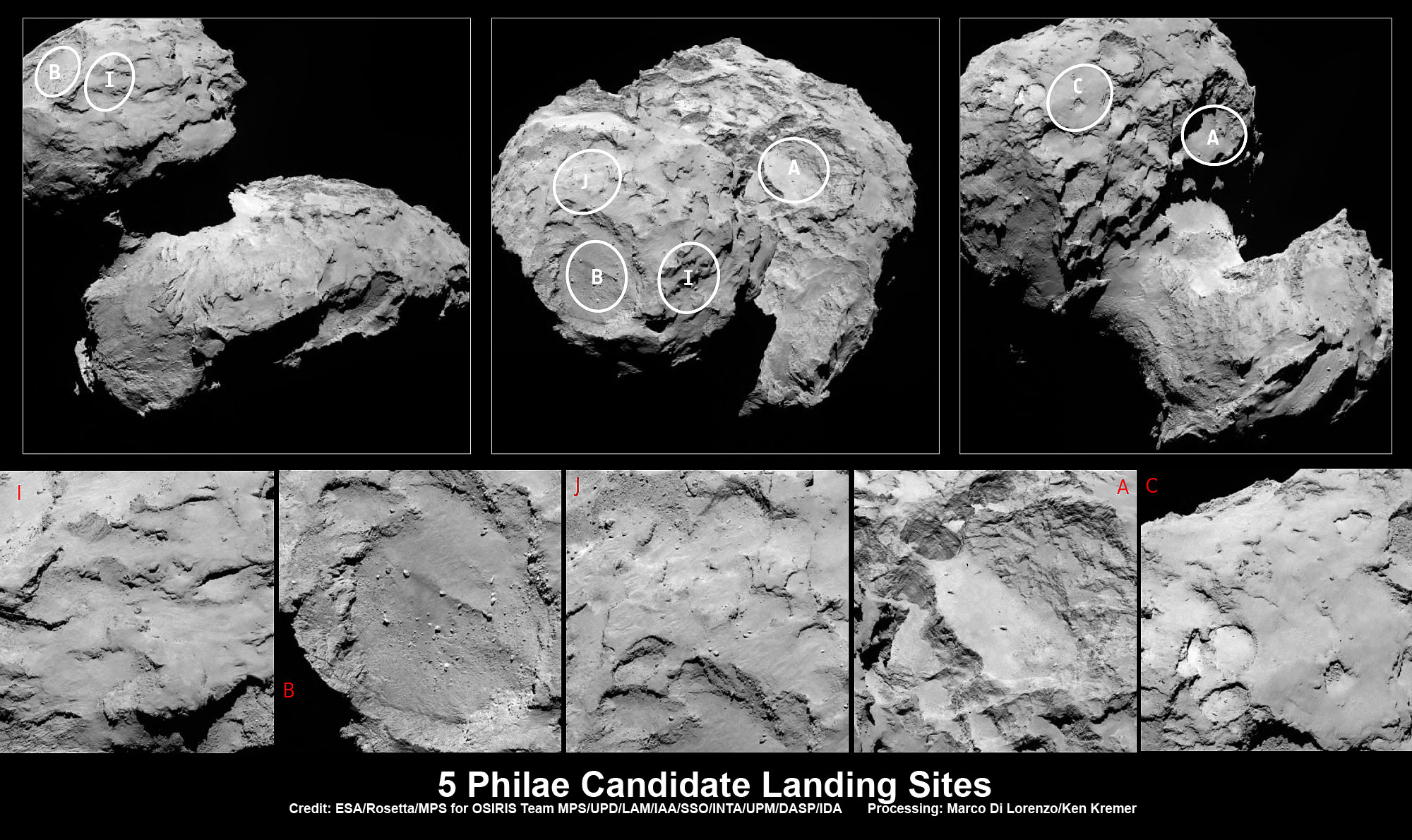

Five candidate sites were identified on Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko for Rosetta’s Philae lander. The approximate locations of the five regions are marked on these OSIRIS narrow-angle camera images taken on 16 August 2014 from a distance of about 100 km. Enlarged insets below highlight 5 landing zones. Credits: ESA/Rosetta/MPS for OSIRIS Team MPS/UPD/LAM/IAA/SSO/INTA/UPM/DASP/IDA Processing: Marco Di Lorenzo/Ken Kremer

Story updated[/caption]

The ‘Top 5’ landing site candidates have been chosen for the Rosetta orbiters piggybacked Philae lander for humankind’s first attempt to land on a comet. See graphics above and below.

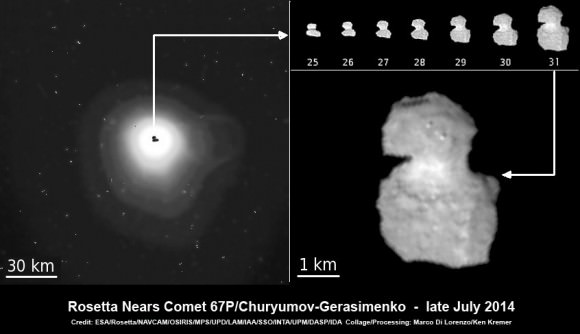

The potential touchdown sites were announce today, Aug. 25, based on high resolution measurements collected by ESA’s Rosetta spacecraft over the past two weeks since arriving at the bizarre and pockmarked Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko on Aug. 6, 2014.

Rosetta is a mission of many firsts, including history’s first ever attempt to orbit a comet for long term study.

Philae’s history making landing on comet 67P is currently scheduled for around Nov. 11, 2014, and will be entirely automatic. The 100 kg lander is equipped with 10 science instruments.

“This is the first time landing sites on a comet have been considered,” said Stephan Ulamec, Lander Manager at DLR (German Aerospace Center), in an ESA statement.

Since rendezvousing with the comet after a decade long chase of over 6.4 billion kilometers (4 Billion miles), a top priority task for the science and engineering team leading Rosetta has been “Finding a landing strip” for the Philae comet lander.

“The challenge ahead is to map the surface and find a landing strip,” said Andrea Accomazzo, ESA Rosetta Spacecraft Operations Manager, at the Aug. 6 ESA arrival live webcast.

So ‘the clock is ticking’ to select a suitable landing zone soon as the comet warms up and the surface becomes ever more active as it swings in closer to the sun and makes the landing ever more hazardous.

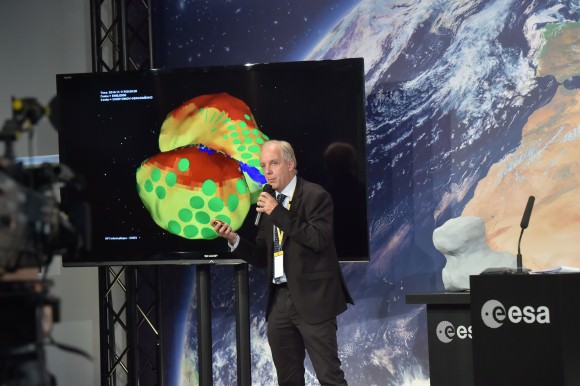

This past weekend, the site selection team met at CNES, Toulouse, France, and intensively discussed and scrutinized a preliminary list of 10 potential sites, and whittled that down to the ‘Top 5.’

Their goal was to find a ‘technically feasible’ touchdown site that was both safe and scientifically interesting.

“The site must balance the technical needs of the orbiter and lander during all phases of the separation, descent, and landing, and during operations on the surface with the scientific requirements of the 10 instruments on board Philae,” said ESA.

They also had to be within an ellipse of at least 1 square kilometer (six-tenths of a square mile) in diameter due to uncertainties in navigation as well as many other factors.

“For each possible zone, important questions must be asked: Will the lander be able to maintain regular communications with Rosetta? How common are surface hazards such as large boulders, deep crevasses or steep slopes? Is there sufficient illumination for scientific operations and enough sunlight to recharge the lander’s batteries beyond its initial 64-hour lifetime, while not so much as to cause overheating?” according to ESA.

The Landing Site Selection Group (LSSG) team was comprised of engineers and scientists from Philae’s Science, Operations and Navigation Centre (SONC) at CNES, the Lander Control Centre (LCC) at DLR, scientists representing the Philae Lander instruments as well as the ESA Rosetta team, which includes representatives from science, operations and flight dynamics.

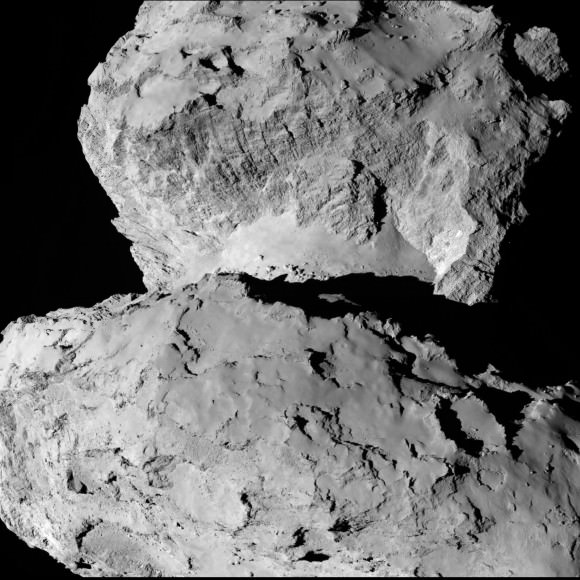

“Based on the particular shape and the global topography of Comet 67P/ Churyumov-Gerasimenko, it is probably no surprise that many locations had to be ruled out,” said Ulamec.

“The candidate sites that we want to follow up for further analysis are thought to be technically feasible on the basis of a preliminary analysis of flight dynamics and other key issues – for example they all provide at least six hours of daylight per comet rotation and offer some flat terrain. Of course, every site has the potential for unique scientific discoveries.”

When Rosetta arrived on Aug. 6, it was initially orbiting at a distance of about 100 km (62 miles) in front of the comet. Carefully timed thruster firings then brought it to within about 80 km distance. And it is moving far closer – to within 50 kilometers (31 miles) and even closer!

Upon arrival the comet was 522 million km from the Sun. As Rosetta escorts the comet looping around the sun, they move much closer. By landing time in mid-November they are only about 450 million km (280 million mi) from the sun.

At closest approach on 13 August 2015 the comet and Rosetta will be 185 million km from the Sun. That corresponds to an eightfold increase in the light received from the Sun.

Therefore Rosetta and Philae will simultaneously study the warming effects of the sun as the comet outgases dust, water and much more.

The short period Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko has an orbital period of 6.5 years.

“The comet is very different to anything we’ve seen before, and exhibits spectacular features still to be understood,” says Jean-Pierre Bibring, a lead lander scientist and principal investigator of the CIVA instrument.

“The five chosen sites offer us the best chance to land and study the composition, internal structure and activity of the comet with the ten lander experiments.”

The ‘Top 5’ zones will be ranked by 14 September. Three are on the ‘head’ and two are on the ‘body’ of the bizarre two lobed alien world.

And a backup landing site will also be chosen for planning purposes and to develop landing sequences.

The ultimate selection of the primary landing site is slated for 14 October after consultation between ESA and the lander team on a “Go/No Go” decision.

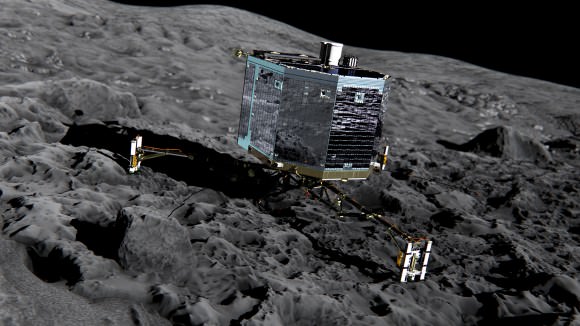

The three-legged lander will fire two harpoons and use ice screws to anchor itself to the 4 kilometer (2.5 mile) wide comet’s surface. Philae will collect stereo and panoramic images and also drill 23 centimeters into and sample its incredibly varied surface.

Why study comets?

Comets are leftover remnants from the formation of the solar system. Scientists believe they delivered a vast quantity of water to Earth. They may have also seeded Earth with organic molecules – the building blocks of life as we know it.

Any finding of organic molecules will be a major discovery for Rosetta and ESA and inform us about the origin of life on Earth.

Read an Italian language version of this story by my imaging partner Marco Di Lorenzo – here

Stay tuned here for Ken’s continuing Earth and Planetary science and human spaceflight news.

Read my Rosetta series here:

Rosetta Moving Closer to Comet 67P Hunting for Philae Landing Site

Coma Dust Collection Science starts for Rosetta at Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko

What’s Ahead for Rosetta – ‘Finding a Landing Strip’ on Bizarre Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko

Rosetta on Final Approach to Historic Comet Rendezvous – Watch Live Here

Rosetta Probe Swoops Closer to Comet Destination than ISS is to Earth and Reveals Exquisite Views

Rosetta Orbiter less than 500 Kilometers from Comet 67P Following Penultimate Trajectory Burn

Rosetta Closing in on Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko after Decade Long Chase

I think B will be the winning site.

I’m hoping for Site A, because from there Philae will have a view of the “neck” and the inward facing side of the smaller lobe, as well as a big stretch of the larger lobe.

A nuclear warhead could perhaps be tried on an outward bound comet. Just in case some comet comes in with our planets adress on it? It would be of great interest to see safely what happens.

I have one ticklish point! Can it really be called ‘landing’? I mean, is the gravity of Comet 67P strong enough for Rosetta to ‘fall’ and stay held? I thought it is more of Rosetta sidling on to the comet and embrace sort of or dig in, to stay together.

Ken, I love your articles, but your unit conversion needs a counter-warping optimizer and a control module 🙂

1 km = approx 0.6 mi – the “six-tenths” you mention in the article belong here, where a *distance* is mentioned.

However, when it comes to *area* instead, 1 square km = 1 km x 1 km = 0.6 mi x 0.6 mi = 0.36 mi², or six tenths of six tenths, or 3.6 tenths of a square mile.

There was a (NASA) mission to Mars that failed because some engineers miscalculated the unit conversion and some others failed to control the numbers. I’d just love to see the whole world switch to the metric units so that no conversion is necessary 🙂

I’m following your articles on UT, and many thanks for all the interesting and up to date details!