What are planetary atmospheres made of? Figuring out the answer to that question is a big step on the road to learning about habitability, assuming that life tends to flourish in atmospheres like our own.

While there is a debate about how indicative the presence of, say, oxygen or water is of life on Earth-like planets, astronomers do agree more study is required to learn about the atmospheres of planets beyond our solar system.

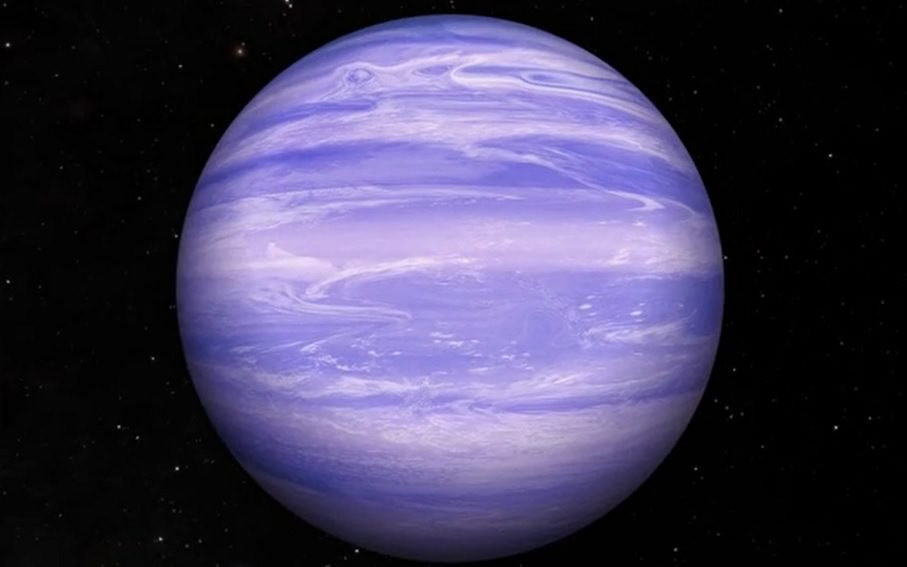

Which is why this latest find is so exciting — one astronomy team says it may have spotted water ice clouds in a brown dwarf (an object between the size of a planet and a star) that is relatively close to our solar system. The find is tentative and also in an object that likely does not host life, but it’s hoped that telescopes may get better at examining atmospheres in the future.

The object is called WISE J085510.83-071442.5, or W0855 for short. It’s the coldest brown dwarf ever detected, with an average temperature between 225 degrees Kelvin (-55 Fahrenheit, or -48 Celsius) and 265 Kelvin (17 Fahrenheit, or -8 Celsius.) It’s believed to be about three to 10 times the mass of Jupiter.

Astronomers looked at W0855 with an infrared mosaic imager on the 6.5-meter Magellan Baade telescope, which is located at Las Campanas Observatory in Chile. The team obtained 151 images across three nights in May 2014.

Astronomers plotted the brown dwarf on a color-magnitude chart, which is a variant of famous Hertzsprung-Russell diagram used to learn more about stars by comparing their absolute magnitude against their spectral types. “Color-Magnitude diagrams are a tool for investigating atmospheric properties of the brown dwarf population as well as testing model predictions,” the authors wrote in their paper.

Based on previous work on brown dwarf atmospheres, the team plotted W0855 and modelled it, discovering it fell into a range that made water ice clouds possible. It should be noted here that water ice is known to exist in all four gas giants of our own Solar System: Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune.

“Non-equilibrium chemistry or non-solar metallicity may change predictions,” the authors cautioned in their paper. “However, using currently available model approaches, this is the first candidate outside our own solar system to have direct evidence for water clouds.”

The research, led by the Carnegie Institution for Science’s Jacqueline Faherty, was published in Astrophysical Journal Letters. A preprint version of the paper is available on Arxiv.

Source: Carnegie Institution for Science