NASA’s Curiosity rover has struck hematite — an iron-oxide mineral often associated with water-soaked environments — in its first drill hole inside the huge Mount Sharp (Aeolis Mons) on Mars. While in this case oxidization is more important to its formation, the sample’s oxidization shows that the area had enough chemical energy to support microbes, NASA said.

Hematite is not a new discovery for Curiosity or Mars rovers generally, but what excites scientists is this confirms observations from the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter that spotted hematite from orbit in the Pahrump Hills, the area that Curiosity is currently roving.

“This connects us with the mineral identifications from orbit, which can now help guide our investigations as we climb the slope and test hypotheses derived from the orbital mapping,” stated John Grotzinger, Curiosity project scientist at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena.

This is the latest in a series of finds for the rover related to habitability. In December 2013, scientists announced it found a zone (dubbed Yellowknife Bay) that was likely an ancient lakebed. But Yellowknife’s mineralogy eluded detection from orbit, likely due to dust covering the rocks.

Hematite is perhaps most closely associated with spherical rocks called “blueberries” that the Opportunity rover discovered on Mars in 2004. While Opportunity’s discovery showed clear evidence of water, the new Curiosity find is more closely associated with oxidization, NASA said.

The new find, contained in a pinch of dust analyzed in Curiosity’s internal Chemistry and Mineralogy (CheMin) instrument, yielded 8% and 4% magnetite. The latter mineral is one way that hematite can be created, should magnetite be placed in “oxidizing conditions”, NASA stated. Previous samples en route to Mount Sharp had concentrations only as high as 1% hematite, but more magnetite. This shows more oxidization took place in this new sample, NASA stated.

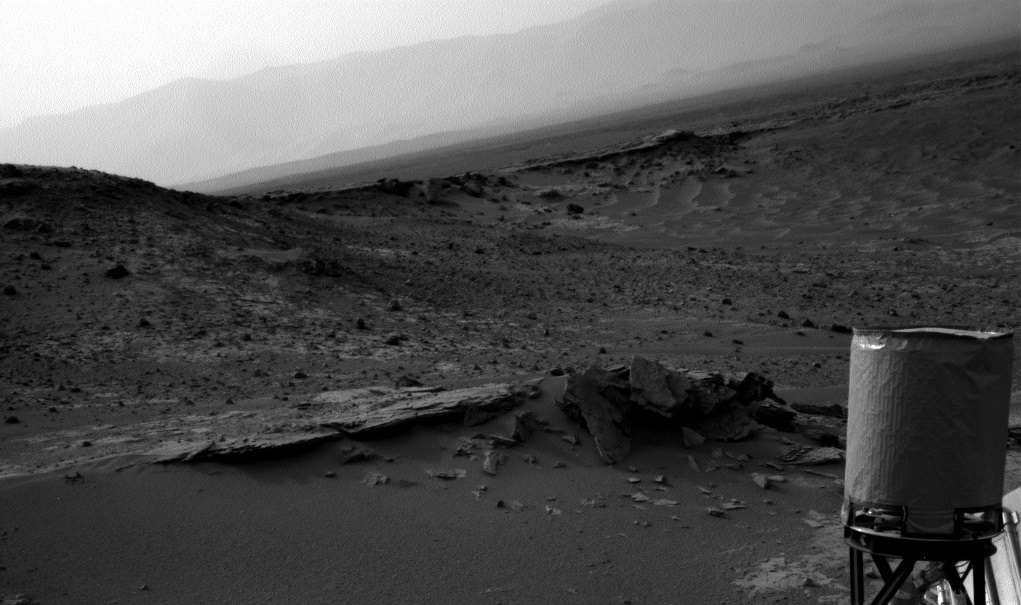

Curiosity will likely stick around Pahrump Hills for at least weeks, perhaps months, until it climbs further up the mountain. Among Mount Sharp’s many layers is one that contains so much hematite (as predicted from orbit) that NASA calls it “Hematite Ridge.”

Source: NASA