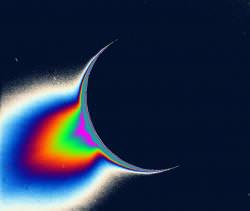

Enceladus has a remarkable secret, and scientists want to know more. Something is keeping the moon warm, and creating great plumes of water ice that spew out into the Saturnian system and even contribute to the rings. NASA is sending the Cassini spacecraft back in for another look in 2008; however, some engineers are concerned that the tiny particles might pose a risk to the spacecraft as it flies right through them.

On March 12th, 2008, Cassini is scheduled to pass only 100 km (62 miles) above the surface of Enceladus – a tremendous scientific opportunity. The spacecraft will give scientists an unprecedented look down onto the “tiger stripe” cracks around Enceladus’ southern pole, and the starfish shaped fissures that emanate away. This could be just the observations they need to finally solve the mystery: where’s all this water ice coming from?

But when Cassini passes this close to the planet, it’s going to be flying right through the plumes. Some scientists are worried that ice grains lofted by the jets will impact the spacecraft and damage its sensitive instruments.

Dr. Larry Esposito, one of the researchers working to understand the source of the plumes is presenting some of his research at the European Planetary Science Congress in Potsdam on Thursday 23rd August.

“These plumes were only discovered two years ago and we are just beginning to understand the mechanisms that cause them. A grain of ice or dust less than two millimetres across could cause significant damage to the Cassini spacecraft if it impacted with a sensitive area. We have used measurements taken with Cassini’s UVIS instrument during a flyby of Enceladus in 2005 to try and understand the shape and density of the plumes and the processes that are causing them.”

The size of the particles is key. Using Cassini’s Ultra-Violet Imaging Spectrograph, scientists were able to calculate the amount of water vapour present in the plumes. They were then able to simulate the speed and density of the particles flowing out of the plumes. This let them calculate the average size of the particles at the point where the plumes will be most dense during Cassini’s encounter in 2008.

While the average-sized particle was 1/1000th the size that would cause damage, Esposito is concerned that there could be larger particles lurking in there as well. It would take very high-pressure jets to loft particles this large, and so far, Esposito hasn’t found any. Right now, he’s estimating the chances for a hit to Cassini to be 1 in 500. Better measurements should give a more precise understanding of the risks involved.

How do you like those odds?