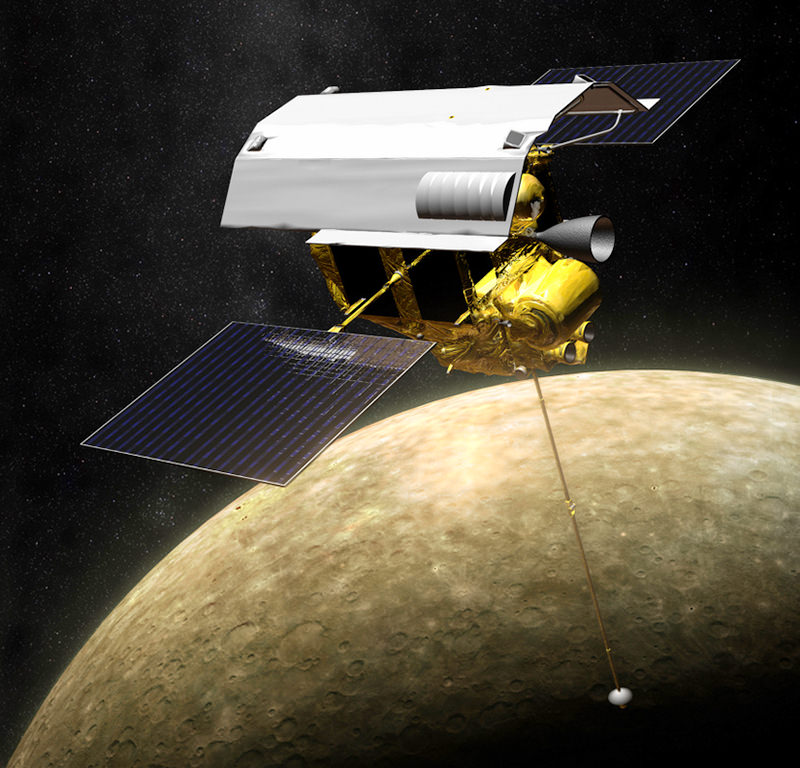

Don’t take these spectacular Mercury images (below the jump) for granted. Three weeks ago, NASA’s orbiting Mercury spacecraft did an engine fire to boost its altitude above the hothouse planet. Another one is scheduled for January.

But all this will do is delay the end of the long-running mission — the first one to orbit Mercury — until early 2015, the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory wrote in an update. These maneuvers “extend orbital operations and delay the probe’s inevitable impact onto Mercury’s surface until early next spring,” the organization said in a statement.

Until MESSENGER (MErcury Surface, Space ENvironment, GEochemistry, and Ranging) flew by Mercury for the first time in January 2008, we knew very little about the planet. The only close-up pictures previously came from Mariner 10, which whizzed by a few times in 1974-75. After a few flybys, MESSENGER settled into orbit in 2011.

In that brief span of years, MESSENGER has taught us that Mercury is a different planet than we imagined. In a statement this August celebrating the spacecraft’s 10th launch anniversary, NASA identified several things that made MESSENGER’s science special:

- Mercury’s high density compared to other planets remains a mystery. MESSENGER investigations found a surface that didn’t have a lot of iron in it, but lots of volatile materials such as sodium and sulfur.

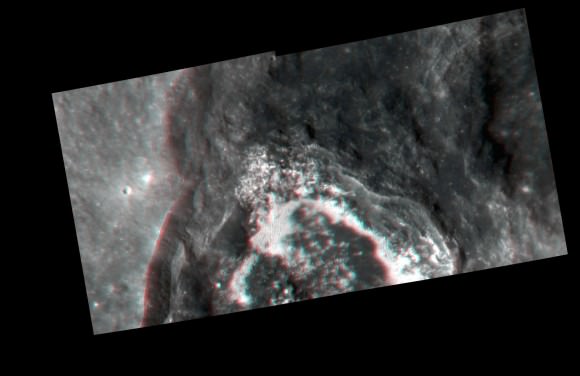

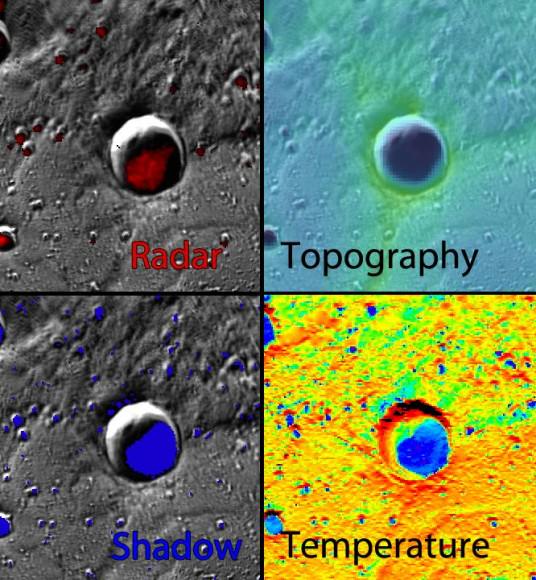

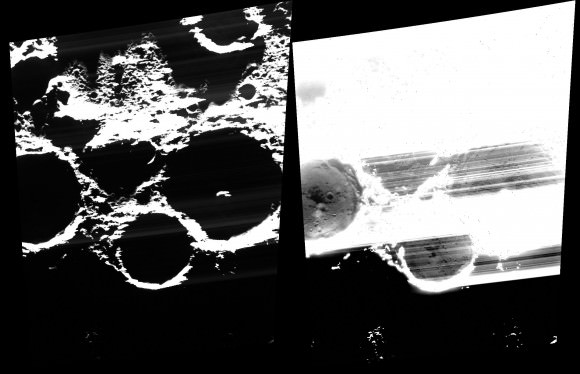

- The surface had volcanoes on it and still has water ice in permanently shadowed craters near the poles.

- Its magnetic field produces weird effects that are still being examined. NASA speaks of “unexplained bursts of electrons and highly variable distributions of different elements” in its tenuous atmosphere, called an exosphere.

“Our only regret is that we have insufficient propellant to operate another 10 years, but we look forward to the incredible science returns planned for the final eight months of the mission,” stated Andy Calloway, MESSENGER mission operations manager at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory, at the time.

MESSENGER has done several orbital-boosting maneuvers in recent months to prolong the mission as possible. The first one in June adjusted its orbit to between 71.4 miles (115 kilometers) and 97.2 miles (156.4 kilometers), while the second in September went lower: a minimum of 15.7 miles (25.2 kilometers) to 58.2 miles (93.7 kilometers).

As of late October, MESSENGER’s minimum altitude was 115.1 miles (185.2 miles) and it took roughly eight hours for it to orbit Mercury. Once it finally crashes, Europe’s and Japan’s BepiColombo is expected to be the next Mercury orbiting mission. It launches in 2016, but will take several flybys past planets to get there and won’t arrive until 2024.

You know… I really look forward to the day when we have at least one probe in orbit around every major body in the solar system at all times gathering data. That’ll be cool.

I know I’m not alone in that;).

If Juno gets to Jupiter before MESSENGER or Venus Express ends their missions, and it you count flyby of Pluto, it is nearly so for the planets and Ceres and the Moon already! Uranus and Neptune are hard to reach. Uranus has a chance of a getting a mission, but Neptune isn’t even discussed. But in a couple of years most will have ended their missions with few replacements.

Why does it take almost as long as to send a spacecraft to Pluto, to send an orbiter to Mercury?

Basically, a spacecraft travelling outward from within the Solar System is ‘climbing’ the Sun’s gravitational well, whereas a spacecraft travelling inward is going ‘downhill’ without any brakes, so it has to use a series of gravity-assisted braking maneuvers around Mercury and Venus to slow it down after being accelerated toward the Sun – hence the ‘scenic’ route!