Cast your gaze up, up, up on the next dark, moonless night and stare into the Great Square of Pegasus. How many stars do you see? Zero? Two? Twenty? If you’d like to find out how dark your sky is, read on.

The Great Square, one of the fall sky’s best known star patterns, rides high in the south at nightfall in mid-December. It forms part of the larger figure of Pegasus the Winged Horse. For our purposes today, we’re going to concentrate on what’s inside the square.

Bounded by Alpheratz (officially belonging to adjacent Andromeda), Scheat, Markab and Algenib, the Great Square is about 15° on a side or one-and-a-half balled fists held at arm’s length.

At first glance, the space appears empty, but a closer look from all but the most light polluted skies will reveal a pair 4th magnitude stars in the upper right quadrant of the square. Fourth magnitude is about the viewing limit from a bright suburban location.

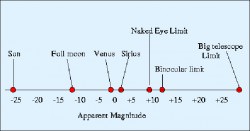

Astronomers use the magnitude scale to measure star and planet brightness. Each magnitude is 2.5 times brighter than the one below it. Aldebaran, which shines at 1st magnitude, is 2.5 times brighter than a 2nd magnitude star, which in turn is 2.5 times brighter than a 3rd magnitude star and so on.

A first magnitude star is 2.5 x 2.5 x 2.5 x 2.5 x 2.5 (about 100) times brighter than a 6th magnitude star. The bigger the magnitude number, the fainter the star. From cities, you might see 3rd magnitude stars if you can block out stray lighting, but a dark country sky will deliver the Holy Grail naked eye limit of magnitude 6. Skywatchers with utterly dark conditions might glimpse stars as faint 7.5. My own personal best is 6.5.

With each drop in magnitude the number of stars you can see increases exponentially. There are only 22 first magnitude or brighter stars compared to 5,946 stars down to magnitude 6.

Ready to stretch your sight and rate your night sky? Step outside at nightfall and allow your eyes to dark-adapt for 20 minutes. With a copy of the map (above) in hand, start with the brightest stars and work your way to the faintest. Each every small step down the magnitude ladder prepares your eyes the next.

With a little effort you should be able to spot the four 4th magnitude range stars. At magnitude 5, you’ll work harder. Moving beyond 5.5 can be very challenging. I revert to averted vision to corral these fainties. Instead of staring directly at the star, play your eye around it. Look a bit to this side and that. This allows a rod-rich part of the retina that’s excellent at seeing faint stuff play through the scene and snatch up the faintest possible stars.

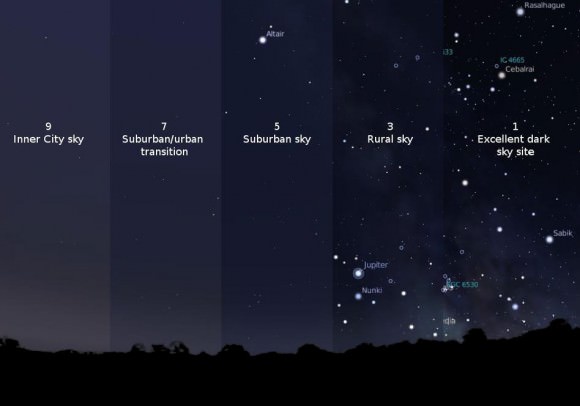

From my house I can pick out about dozen points of light inside the Square on a moonless night. How many will you see? Once you know your magnitude limit, compare your result to John Bortle’s Dark Sky Scale … and weep. No, just kidding. But his Class 1 excellent sky includes a description of seeing stars down to magnitude 8 and the summer Milky Way casting shadows.

Hard to believe that before about 1790, when gas lighting was introduced in England, Class 1 skies were the norm across virtually the entire planet. Nowadays, most of us have to drive a hundred miles or more to experience true, untrammeled darkness.

Have fun with the challenge and let us know in the comments area how you do. Here’s hoping you find the Great Square far from vacant.

Great Basin National Park In Nevada has the 7th darkest night sky in the lower 48 AND the have an astronomy program. Ask for Ranger Kelly Carroll