On April 24, 1990, the Hubble Space Telescope was launched from Kennedy Space Center into low Earth orbit. Hubble was the first telescope designed to operate in space, so it was able to avoid interference from Earth’s atmosphere – an inconvenience that had limited astronomers since they first looked up to the skies. However, scientists quickly realized that something was wrong; the images were blurry. Despite being among the most precisely ground instruments ever made, the primary mirror in the Hubble was about 2,200 nanometers too flat at the perimeter (for reference, the width of a typical sheet of paper is about 100,000 nanometers). Luckily, there was a solution.

Hubble was designed to be serviced in space. As NASA writes on the telescope’s website, “a series of small mirrors could be used to intercept the light reflecting off the mirror, correct for the flaw, and bounce the light to the telescope’s science instruments.” A series of five missions lasting from 1993 to 2009 was devised to correct the mirror and perform various upgrades. Despite being the first of their kind, the missions were declared a resounding success – and they enabled the Hubble Space Telescope to remain operational to this day. Many of Hubble’s images are among the most incredible ever produced by mankind, yet few people know anything about the remarkable men and women who made them possible.

See an exclusive gallery of images from the book here.

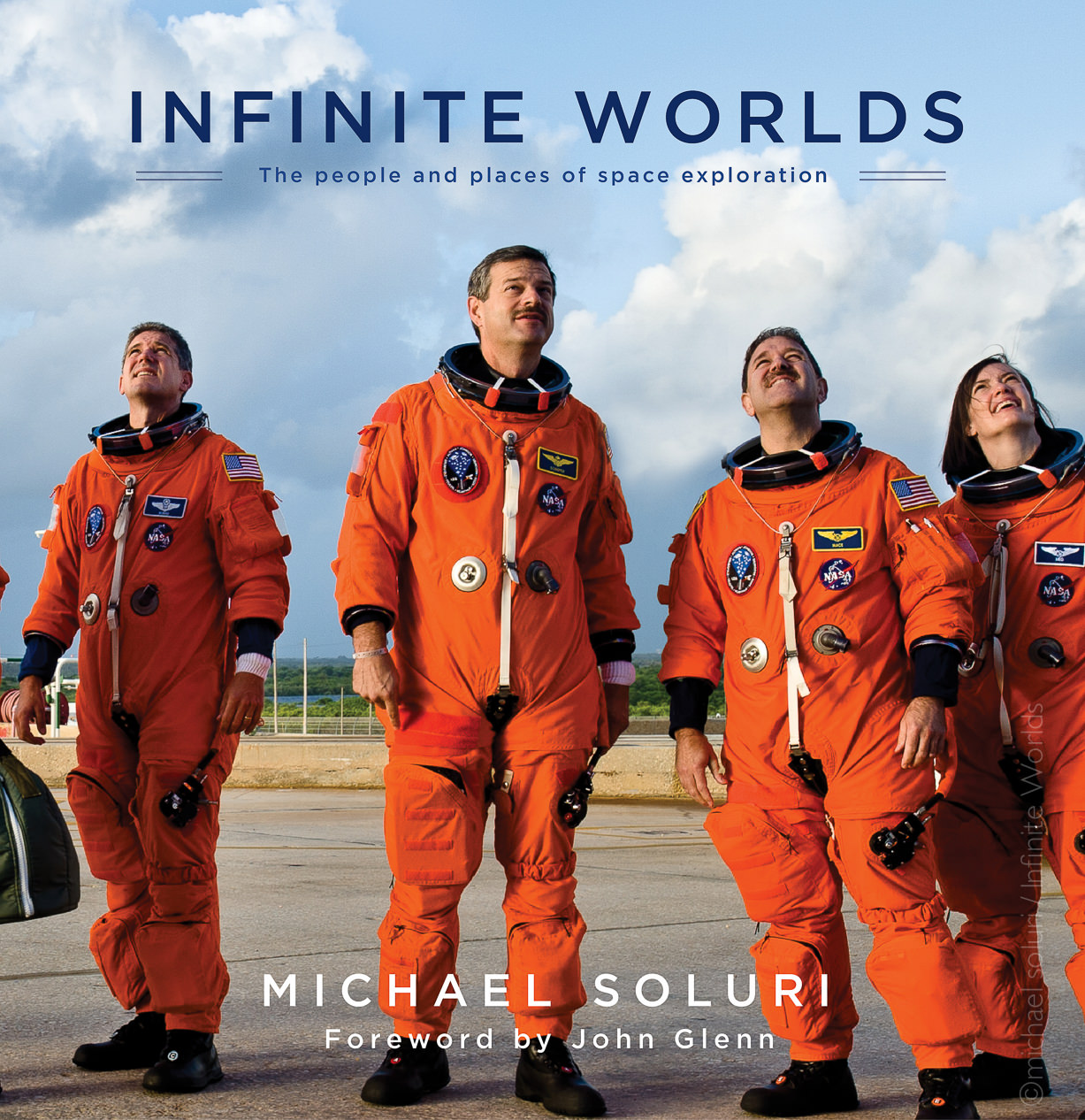

Infinite Worlds: People & Places of Space Exploration, the latest book from photographer Michael Soluri, documents the people who worked on the last of these repair missions, STS-125 (also known as Hubble Space Telescope Servicing Mission 4 [HST-SM4]). The nearly two-week journey aboard Space Shuttle Atlantis saw the successful installation of two new instruments and the repair of two others. Like the four other shuttle crews that came before them, the men and women aboard STS-125 enabled Hubble to see deeper and farther into the past than ever before.

Michael Massimino, a veteran of the earlier STS-109 mission, is one of these people. Massimino and Soluri became fast friends after a chance encounter, when Soluri asked: “What is the quality of light really like in space?” Following their discussion, Massimino asked Soluri to teach him and the rest of the crew how to take photographs that would better communicate their experiences in space. Astronauts are always taking pictures, but the lighting in space is, understandably, not always ideal. Like Soluri himself in Infinite Worlds, the astronauts repairing Hubble were looking for better ways to communicate the beauty of space travel through photography.

Soluri was granted unprecedented access to document the people and events behind the mission throughout a period of more than four years. The photographs in the book “give deserved attention to a few of the many thousands of people who worked on the Space Shuttle and Hubble Space Telescope programs,” reads an inspiring foreword by John Glenn, the first American to orbit the Earth. Infinite Worlds reveals a side of space travel that most of us would never otherwise see, including the training sessions, tools, and trials that make success possible. NASA, notorious for keeping their employees tightly scripted and inaccessible, rarely grants such access – and with the closing of the Space Shuttle Program in 2011, such intimacy may never be seen again.

Science is a cooperative discipline, but most people only ever see the results. The tireless work of thousands of individuals is often taken for granted and forgotten. Although many people still hold the false idea that scientific accomplishments are made by individual geniuses working in an armchair, now more than ever before we are entering an age where science is performed by large teams working cooperatively. To mention just one example, CERN hosts scientists of more than 100 nationalities. As Jill McGuire, a manager at Goddard Space Flight Center, writes about the field in the book, “the best way to move forward in the business was to get my hands dirty by working with the skilled machinists and technicians in the branch to learn everything I could.”

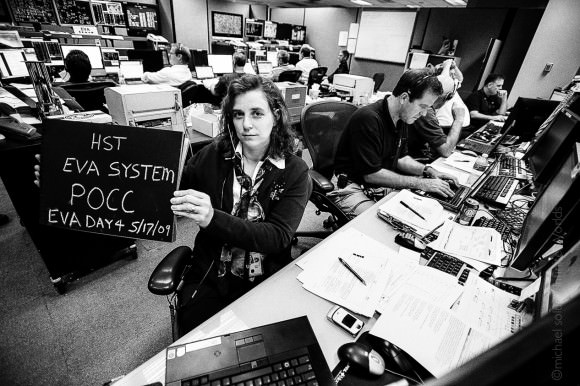

Infinite Worlds grants readers an exhilarating glimpse into this cooperative world. One particularly inspiring section follows the immediate buildup to the launch of STS-125. The transcript of the pre-launch quality check is paralleled by images of the situation as it happened. Black and white photographs from both cockpit and control room highlight the tension behind “the most risky thing NASA does,” according to Space Shuttle Launch Director Michael Leinbach. He continues, “they were real people with real families, real children, real lives.” Infinite Worlds reminds us of this: the work behind every scientific breakthrough is not magic, but rather the result of talented and dedicated individuals.

As we approach the 25th anniversary of the Hubble Space Telescope’s launch and look to the future, a book like Infinite Worlds is more relevant now than ever before. The beautiful photographs in Soluri’s book tell two kindred stories: not only the heroic report of repairing a multi-billion dollar piece of equipment, but also a unique glimpse at the inspiring men and women who made it all possible. Whether humanity’s next missions are to Mars, Europa, or elsewhere, one thing will remain constant – we will only reach the stars through the work of exceptional people.

Infinite Worlds is available at Amazon, Barnes and Noble, Indiebound, iBooks, and Google Play.

Learn more about Michael Soluri at his website.

Several of Soluri’s images of the SM4’s EVA tools and photos by the Atlantis crew are part of an exhibition at the Smithsonian Air and Space Museum, Outside the Spacecraft: 50 Years of Extra-Vehicular Activity, on view at the Air and Space Museum through June 8. There’s also an online exhibition.

Soluri will give a presentation and do a book signing on April 11, 2015 at the Smithsonian’s Hirshhorn Museum & Sculpture Garden. Soluri will be joined by four individuals who played key roles in Service Mission SM4: astronaut Scott Altman, the STS-125 shuttle commander; David Leckrone, senior project scientist; Christy Hansen, EVA spacewalk flight controller and astronaut instructor; and Hubble systems engineer Ed Rezac. More information on that event can be found here.