An interesting multiple star discovery turned up in the ongoing hunt for exoplanetary systems.

The discovery was announced by Marcus Lohr of Open University early this month at the National Astronomy Meeting that was held at Venue Cymru in Llandudno, Wales.

The discovery involves as many as five stars in a single stellar system, orbiting in a complex configuration.

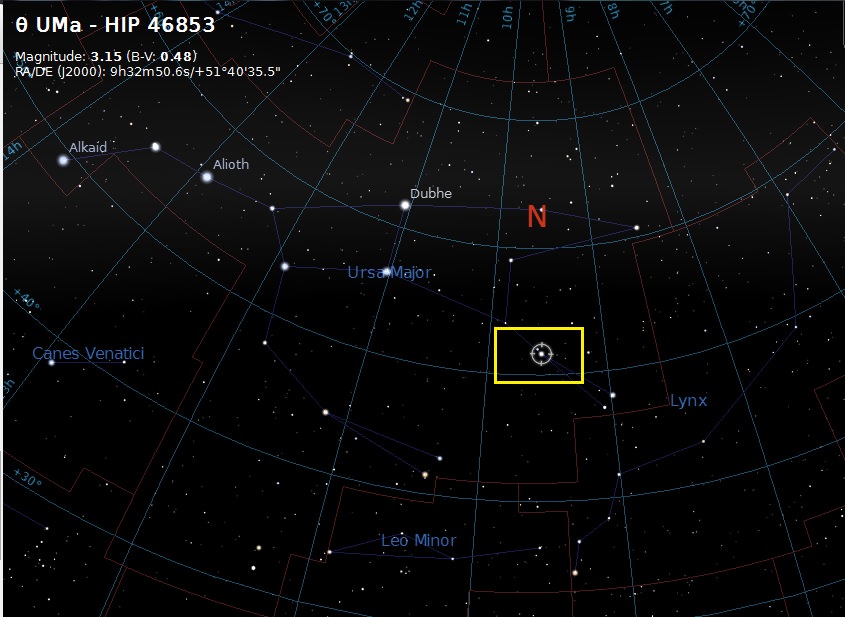

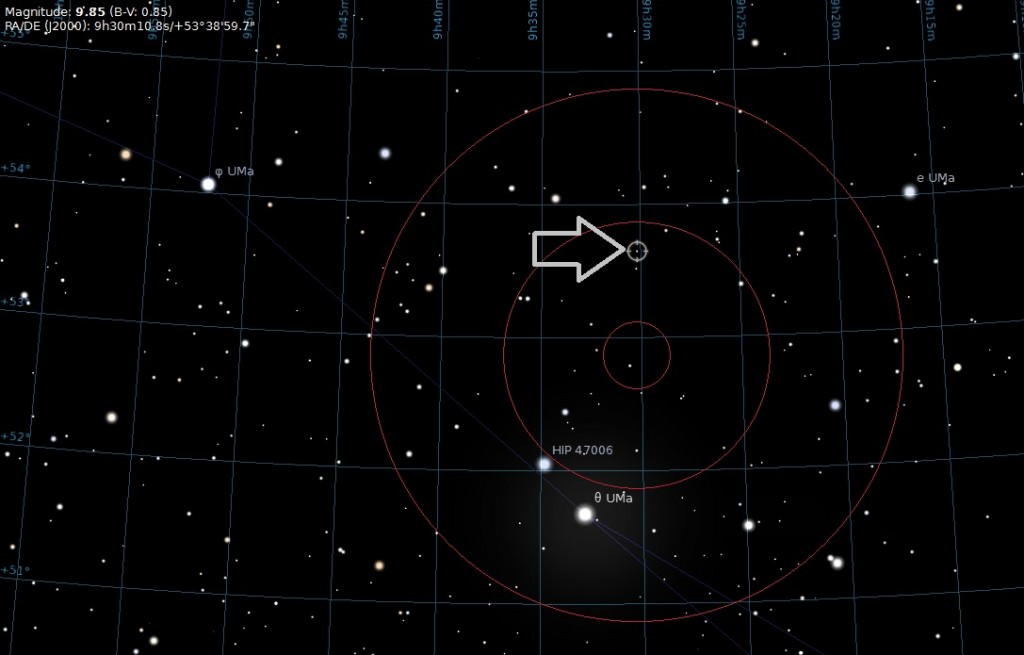

The name of the system, 1SWASP J093010.78+533859.5, is a phone number-style designation related to the SuperWASP exoplanet hunting transit survey involved with the discovery. The lengthy numerical designation denotes the system’s position in the sky in right ascension and declination in the constellation Ursa Major.

And what a bizarre system it is. The physical parameters of the group are simply amazing, though not as unique as some media outlets have led readers to believe. What is amazing is the fact that both pairs of binaries in the quadruple group are also eclipsing along our line of sight. Only five other quadruple eclipsing binary systems of this nature are known, to include BV/BW Draconis and V994 Herculis.

The very fact that the orbits of both pairs of stars are in similar inclinations will provide key insights for researchers as to just how this system formed.

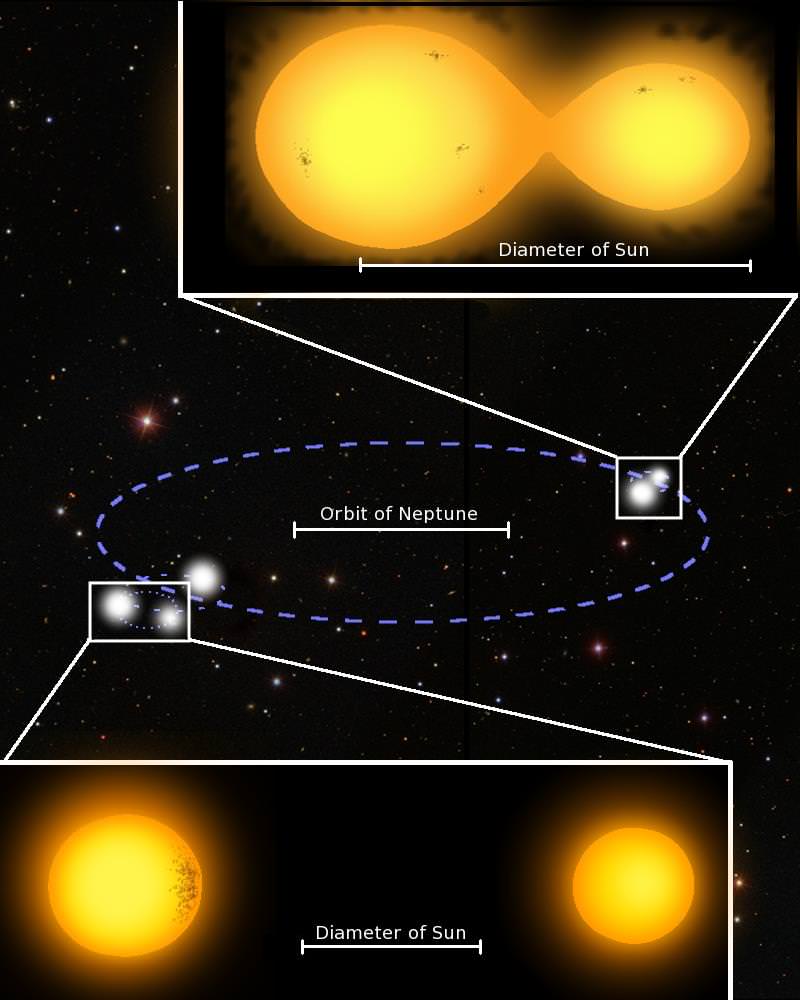

The first pair in the system are contact binaries of 0.9 and 0.3 solar masses respectively in a tight embrace revolving about each other in just under six hours. Contact binaries consist of distorted stars whose photospheres are actually touching. A famous example is the eclipsing contact binary Beta Lyrae.

An animation of the orbits of the contact binary pair Beta Lyrae captured using the CHARA interferometer. Image credit: Ming Zhao et al. ApJ 684, L95

A closer analysis of the discovery revealed another pair of detached stars of 0.8 and 0.7 solar masses orbiting each other about 21 billion kilometres (140 AUs distant) from the first pair. You could plop the orbit of Pluto down between the two binary pairs, with room to spare.

But wait, there’s more. Astronomers use a technique known as spectroscopy to tease out the individual light spectra signatures of close binaries too distant to resolve individually. This method revealed the presence of a fifth star in orbit 2 billion kilometers (13.4 AUs, about 65% the average distance from Uranus to the Sun) around the detached pair.

“This is a truly exotic star system,” Lohr said in a Royal Society press release. “In principle, there’s no reason it couldn’t have planets in orbit around each of the pairs of stars.”

Indeed, ‘night’ would be a rare concept on any planet in a tight orbit around either binary pair. In order for darkness to occur, all five stellar components would have to appear near mutual conjunction, something that would only happen once every orbit for the hypothetical world.

Such a planet is a staple of science fiction, including Tatooine of Star Wars fame (which orbits a relatively boring binary pair), and the multiple star system of the Firefly series. Perhaps the best contender for a fictional quadruple star system is the 12 colonies of the re-imagined Battlestar Galactica series, which exist in a similar double-pair configuration.

How rare is this discovery, really? Multiple systems are more common than solitary stars such as our Sun by a ratio of about 2:1. In fact, it’s been suggested by rare Earth proponents that life arose here on Earth in part because we have a stable orbit around a relatively placid lone star. The solar system’s nearest stellar neighbor Alpha Centauri is a triple star system. The bright star Castor in the constellation of Gemini the Twins is a famous multiple heavyweight with six components in a similar configuration as this month’s discovery. Another familiar quadruple system to backyard observers is the ‘double-double’ Epsilon Lyrae, in which all four components can be split. Mizar and Alcor in the handle of the Big Dipper asterism is another triple-pair, six-star system. Another multiple, Gamma Velorum, may also possess as many as six stars. Nu Scorpii and AR Cassiopeiae are suspected septuple systems, each perhaps containing up to seven stars.

Fun fact: Gamma Velorum is also informally known as ‘Regor,’ a backwards anagram play on Apollo 1 astronaut ‘Roger’ Chaffee’s name. The crew secretly inserted their names into the Apollo star maps during training!

What is the record number of stars in one system? Hierarchy 3 systems such as Castor are contenders. A.A. Tokivinin’s Multiple Star Catalogue lists five components in a hierarchy 4 system in Ophiuchus named Gliese 644AB, with the potential for more.

How many stars are possible in one star system? Certainly, a hierarchy 4 type system could support up the eight stars, though to our knowledge, no example of such a multiple star system has yet been confirmed. Still, it’s a big universe out there, and the cosmos has lots of stars to play with.

And you can see 1SWASP J093010.78+533859.5 for yourself. At 250 light years distant, the +9th magnitude binary is about 1.5 degrees north-northwest of the star Theta Ursa Majoris, and is an tough but not impossible split with a separation of 1.88” between the two primary pairs.

Congrats to the team on this amazing discovery… to paraphrase Haldane, the Universe is proving to be stranger than we can imagine!

Nice!

“Multiple systems are more common than solitary stars such as our Sun by a ratio of about 2:1. ”

I’ve never been sure if this statistic counts actual stars or systems!

The assertion that a majority of stars are multiples is not without some controversy, and could be the subject of its own post. One objection is that our sampling of local stars that can be directly observed may not be typical of the galaxy as a whole, but evidence strongly suggests that a majority of suns have stellar companions.

Thanks David, I don’t doubt the general idea but I just wonder about the precise meaning of the 2:1 ratio.

Supposing stars only came in singles and pairs, counting systems yields 4 stars ‘living in pairs’ for 1 single star. Counting stars yields 1 pair system for 1 single system.

Not exactly the same meaning!

I see what you’re saying. In this case, it’s 1 unit= 1 star system. The 2:1 = 1/3 ratio was tough to pin down in research, would love to see if anyone has done a definitive study on the exact statistical ratio of single systems to multiples.

Does the high incidence of multiple star systems decrease or increase the likelihood of planets in orbit around them?

Interesting question… I would say decrease, as multiple star systems would get chaotic over time. As the exoplanet catalog grows, we may soon have some hard data on if this is true or not.