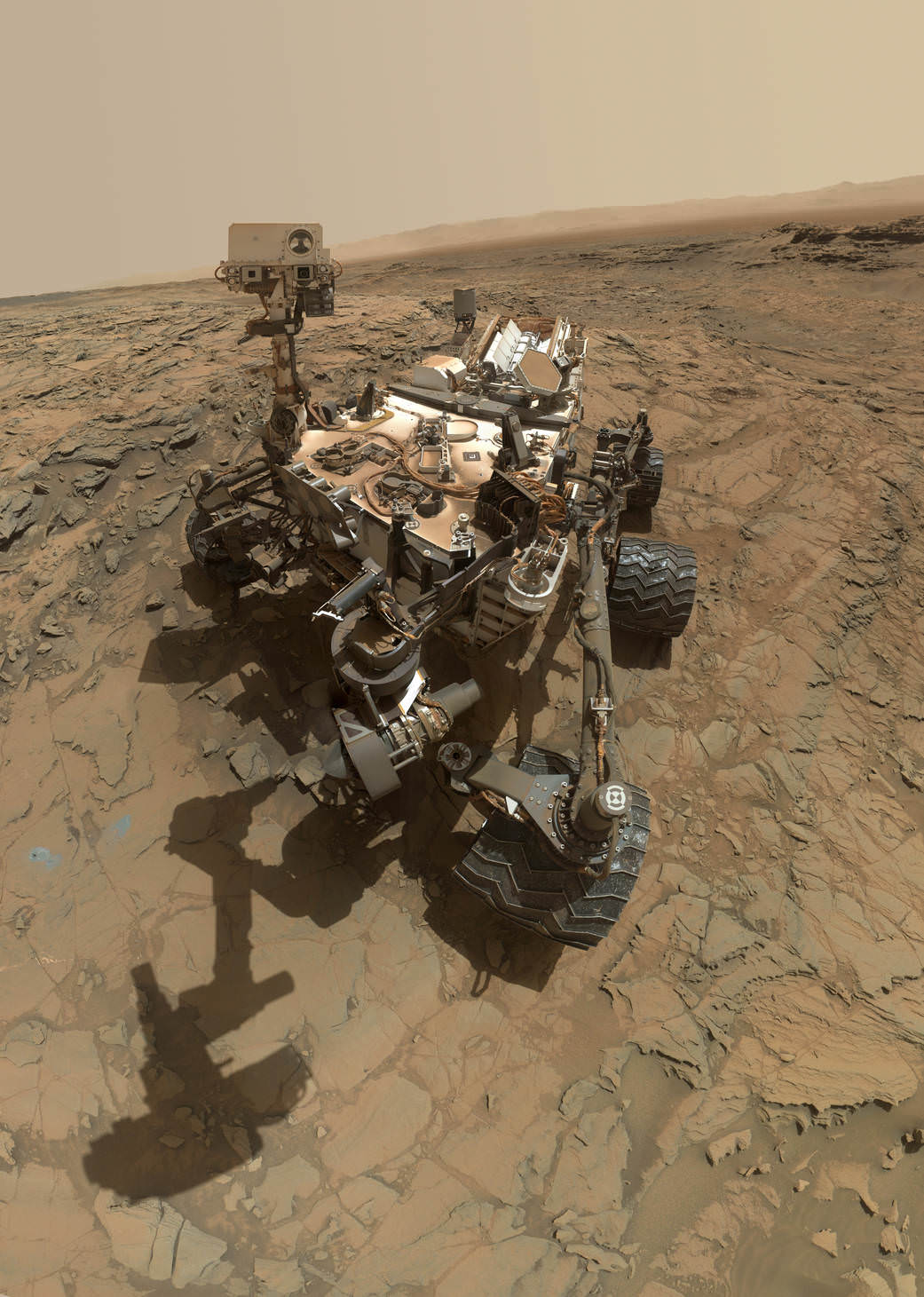

This self-portrait of NASA’s Curiosity Mars rover shows the vehicle at the “Big Sky” site, where its drill collected the mission’s fifth taste of Mount Sharp, at lower left corner. The scene combines images taken by the Mars Hand Lens Imager (MAHLI) camera on Sol 1126 (Oct. 6, 2015). Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/MSSS

See below navcam drilling photo mosaic at Big Sky[/caption]

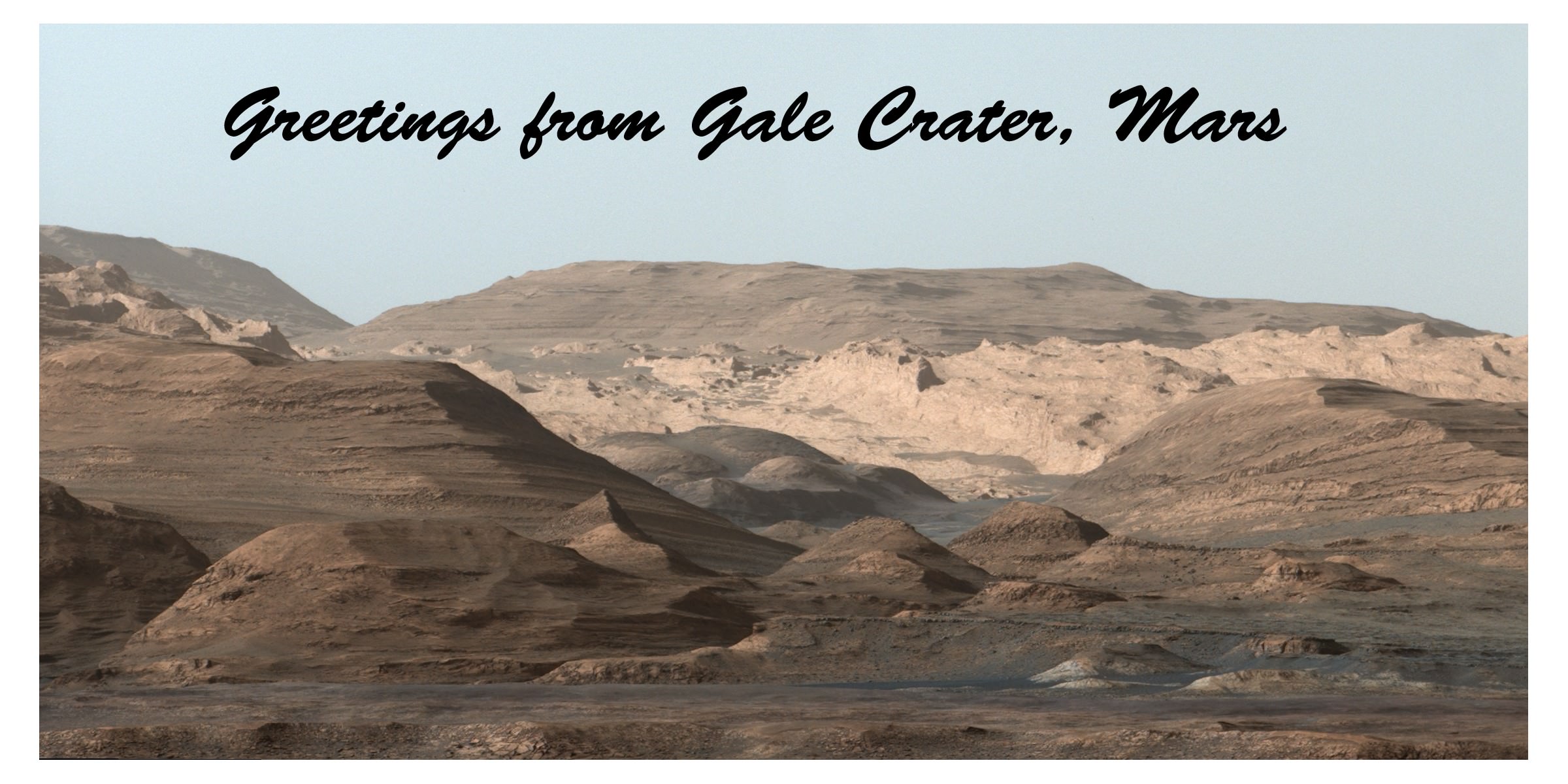

NASA’s Curiosity rover has managed to snap another gorgeous selfie while she was hard at work diligently completing her newest Martian sample drilling campaign – at the ‘Big Sky’ site at the base of Mount Sharp, the humongous mountain dominating the center of the mission’s Gale Crater landing site – which the science team just confirmed was home to a life bolstering ancient lake based on earlier sample analyses.

And the team is already actively planning for the car sized robots next drill campaign in the next few sols, or Martian days!

Overall ‘Big Sky’ marks Curiosity’s fifth ‘taste’ of Mount Sharp – since arriving at the mountain base one year ago – and eighth drilling operation since the nail biting Martian touchdown in August 2012.

NASA’s newly published self-portrait was stitched from dozens of images taken at Big Sky last week on Oct. 6, 2015, or Sol 1126, by the high resolution Mars Hand Lens Imager (MAHLI) color camera at the end of the rover’s 7 foot long robotic arm. The view is centered toward the west-northwest.

At Big Sky, the Curiosity Mars Science Laboratory (MSL) bored into an area of cross-bedded sandstone rock in the Stimson geological unit on Sept. 29, or Sol 1119. Stimson is located on the lower slopes of Mount Sharp inside Gale Crater.

“Success! Our drill at “Big Sky” went perfectly!” wrote Ryan Anderson, a planetary scientist at the USGS Astrogeology Science Center and a member of the Curiosity ChemCam team.

The drill hole is seen at the lower left corner of the MAHLI camera selfie and appears grey along with grey colored tailing – in sharp contrast to the rust red surface. The hole itself is 0.63 inch (1.6 centimeters) in diameter.

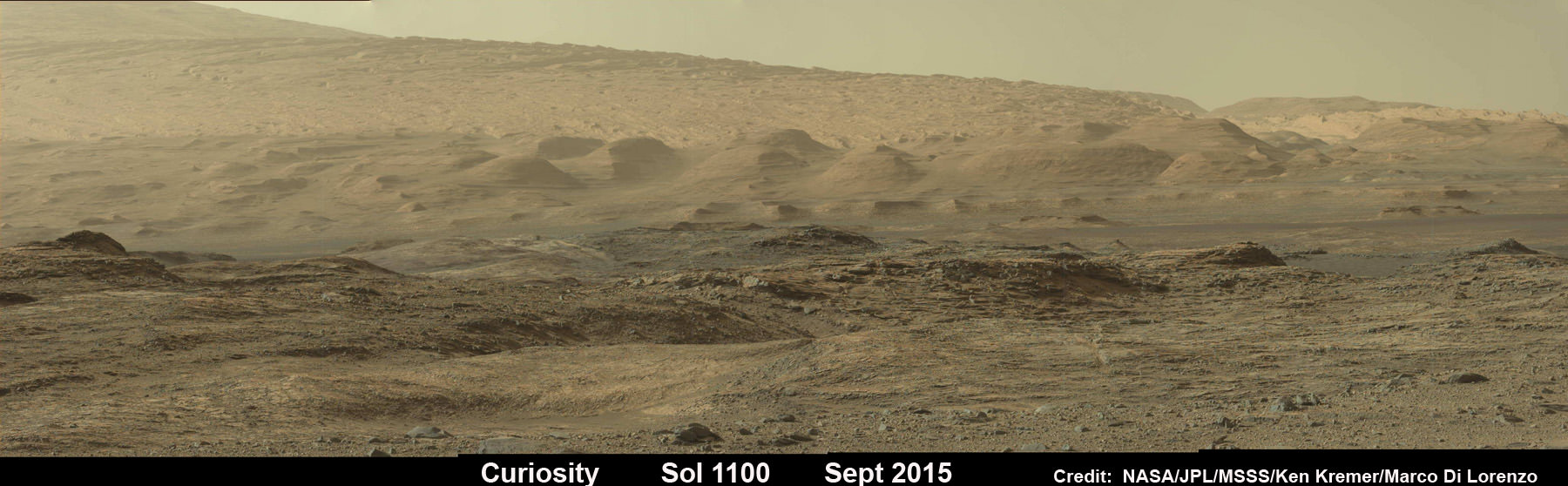

Another panoramic view of the ‘Big Sky’ location shot from the rover’s eye perspective with the mast mounted Navcam camera, is shown in our photo mosaic view herein and created by the image processing team of Ken Kremer and Marco Di Lorenzo. The navcam mosaic was stitched from raw images taken up to Sol 1119 and colorized.

“With Big Sky, we found the ordinary sandstone rock we were looking for,” said Curiosity Project Scientist Ashwin Vasavada, in a statement.

The Big Sky drilling operation is part of a coordinated multi-step campaign to examine different types of sandstone rocks to provide geologic context.

“It also happens to be relatively near sandstone that looks as though it has been altered by fluids — likely groundwater with other dissolved chemicals. We are hoping to drill that rock next, compare the results, and understand what changes have taken place.”

Per normal operating procedures, the Big Sky sample was collected for analysis of the Martian rock’s ingredients in the rover’s two onboard laboratories – the Chemistry and Mineralogy X-Ray diffractometer (CheMin) and the Sample Analysis at Mars (SAM) instrument suite.

“We are all eagerly looking forward to the CheMin results from Big Sky to compare with our previous results from “Buckskin”! noted Anderson.

This past weekend, Curiosity successfully fed pulverized and sieved samples of Big Sky to the inlet ports for both CheMin and SAM on the rover deck.

“The SAM analysis of the Big Sky drill sample went well and there is no need for another analysis, so the rest of the sample will be dumped out of CHIMRA on Sol 1132,” said Ken Herkenhoff, Research Geologist at the USGS Astrogeology Science Center and an MSL science team member, in a mission update.

Concurrently the team is hard at work readying the rover for the next drill campaign within days, likely at a target dubbed “Greenhorn.”

So the six wheeled rover drove about seven meters to get within range of Greenhorn.

With the sample deliveries accomplished, attention shifted to the next drilling campaign.

Today, Wednesday, Oct. 14, or Sol 1133, Curiosity was commanded “to dump the “Big Sky” sample and “thwack” CHIMRA (the Collection and Handling for in-Situ Martian Rock Analysis) to clean out any remnants of the sample,” wrote Lauren Edgar, a Research Geologist at the USGS Astrogeology Science Center and a member of MSL science team, in a mission update.

The ChemCam and Mastcam instruments are simultaneously making observations of the “Greenhorn” and “Gallatin Pass” targets “to assess chemical variations across a fracture.”

Curiosity has already accomplished her primary objective of discovering a habitable zone on the Red Planet – at the Yellowknife Bay area – that contains the minerals necessary to support microbial life in the ancient past when Mars was far wetter and warmer billions of years ago.

As of today, Sol 1133, October 14, 2015, she has driven some 6.9 miles (11.1 kilometers) kilometers and taken over 274,600 amazing images.

Stay tuned here for Ken’s continuing Earth and planetary science and human spaceflight news.

May I ask perhaps a very stupid question?

Why in all that rovers “selfies” from mars it is never visible the camera mast?

Thanks

Andrea

Hi Andrea! It’s a very reasonable question. The “selfies” are actually a mosaic of several different photographs with the “camera mast” removed because it would cover a good portion of the rover itself. The only clue that you have that the mast is really there is that bizarre shadow on the lower left of that first picture, it’s a shadow of something that doesn’t seem to exist in the rest of the photo.

Polly, Thank you very much for the nice answer!

We’ve just answered your question in a new post here: http://www.universetoday.com/122883/why-dont-we-see-the-curiosity-rovers-arm-when-it-takes-a-selfie/ And contrary to what pollydextrous said, the rover arm (the camera used is not on the mast, but on the robotic arm) is never in any of the images because it is always behind the camera. The article explains it and includes a great video from JPL that shows how it works.

Nancy, Thank you very much, I am happy my question prompted a new post on the subject. The Jpl’s video explains it clearly.

Cheers and keep up the good work!

Andrea G.

why don’t you just stop calling it a selfie? you’re a scientific site, not a tabloid.