The New Horizons spacecraft has been slowly sending back all the images and data it gathered during its July flyby of the Pluto system. The latest batch of images to arrive here on Earth contains some of the highest resolution views yet that it captured of Pluto’s surface, taken during the spacecraft’s closest approach.

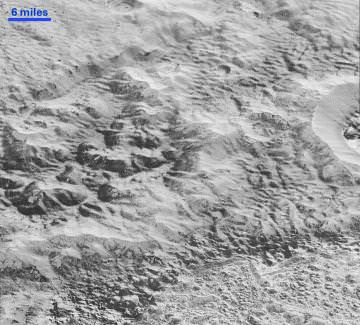

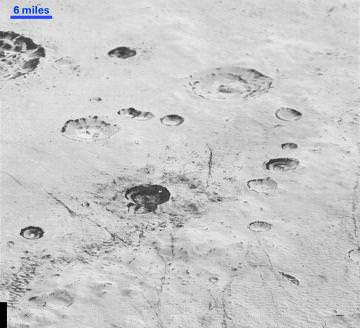

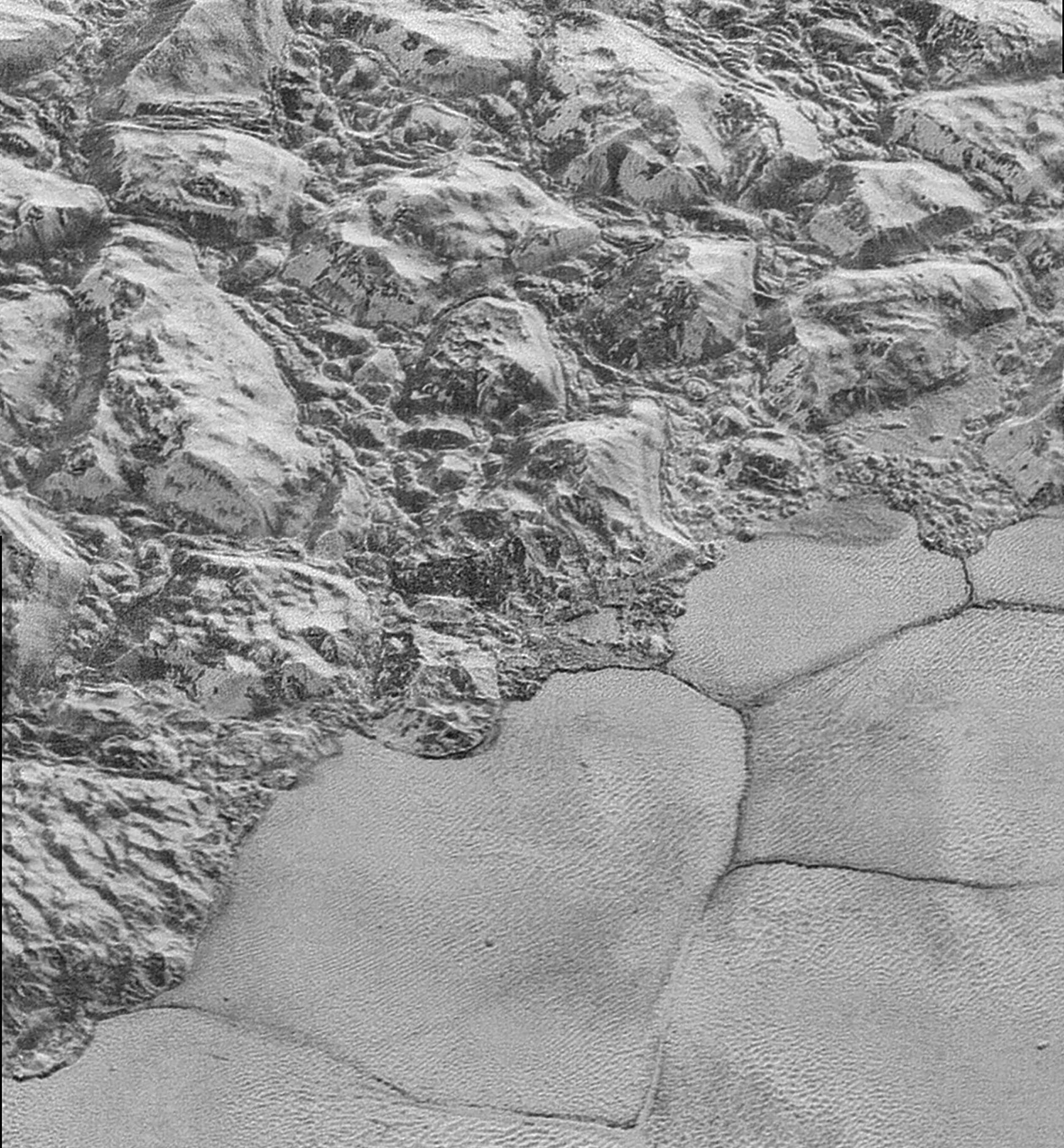

The images show a wide variety of spectacular craters, mountains and glaciers. The New Horizons team said the images have resolutions of about 250-280 feet (77-85 meters) per pixel – revealing features less than half the size of a city block on the diverse surface of the distant dwarf planet. The images are six times better than the resolution of the global Pluto map New Horizons obtained.

“These close-up images, showing the diversity of terrain on Pluto, demonstrate the power of our robotic planetary explorers to return intriguing data to scientists back here on planet Earth,” said John Grunsfeld, former astronaut and associate administrator for NASA’s Science Mission Directorate. “New Horizons thrilled us during the July flyby with the first close images of Pluto, and as the spacecraft transmits the treasure trove of images in its onboard memory back to us, we continue to be amazed by what we see.”

The images here are from a strip of Pluto’s surface 50 miles (80 kilometers) wide about 500 miles (800 kilometers) northwest of the informally named Sputnik Planum, across the al-Idrisi mountains, onto the shoreline of Sputnik and then across its icy plains. The full mosaic of the images can be seen here. Below, the mosaic can be seen in video form:

These images were taken by the Long Range Reconnaissance Imager (LORRI) aboard New Horizons, in a timespan of about a minute, about 11:36 UTC on July 14, 2015 – just about 15 minutes before New Horizons’ closest approach to Pluto – from a range of just 10,000 miles (17,000 kilometers).

Why are these higher resolution than previous images? The New Horizons team explained that they were obtained with an unusual observing mode; instead of working in the usual “point and shoot,” LORRI snapped pictures every three seconds while the Ralph/Multispectral Visual Imaging Camera (MVIC) aboard New Horizons was scanning the surface. This mode requires unusually short exposures to avoid blurring the images.

The best part is that more high resolution images like these are on the way. And perhaps some 3-D versions, too:

Next set of high-res pics on the way. Relax this wknd reading our latest blog about movie-making of #PlutoFlyby. pic.twitter.com/xxbwWInXCM

— NASA New Horizons (@NASANewHorizons) December 5, 2015

It will take at least a year for all the images and data gathered during the July flyby to be sent back to Earth. The data is stored on two onboard, solid-state, 8 gigabyte memory banks. The spacecraft’s main processor compresses, reformats, sorts and stored the data on a recorder, similar to a flash memory card for a digital camera.

One issue for why it is taking so long to get all the data returned is simply the time it takes to get data from New Horizons as it speeds even farther away from Earth, past the Pluto system. Even moving at light speed, the radio signals from New Horizons containing data need more than 4 ½ hours to cover the 4 billion km (3 billion miles) to reach Earth.

But the biggest issue is the relatively low “downlink” rate at which data can be transmitted to Earth, especially when you compare it to rates now common for high-speed Internet surfers. The average downlink rate is between 1-4 kilobits per second, depending on how the data is sent and which Deep Space Network antenna is receiving it. Plus, the spacecraft runs on between 2-10 watts of power, so there’s not a lot of power available to speed up the return rate.

New Horizons’ Principal Investigator Alan Stern described these latest images a “breathtaking,” and other science team members continue to be blown away by the variety of surface features they are seeing on Pluto.

“The mountains bordering Sputnik Planum are absolutely stunning at this resolution” added New Horizons science team member John Spencer. “The new details revealed here, particularly the crumpled ridges in the rubbly material surrounding several of the mountains, reinforce our earlier impression that the mountains are huge ice blocks that have been jostled and tumbled and somehow transported to their present locations.”

See more info about these images here.

Counting the fresh craters in the dunes might be a job for Zoo Universe to distribute? I wonder how fast those dunes are moving?

…more and more character with each new set of images.

Lots of interesting bits close up in the “Badlands” picture. Some crater walls and land ridges have white tracing down hill and some have black/dark traces, and either could be separated from the top surface by a contrasting edge or joined to the edge all on a scale a fraction of a mile.

The MountainousShoreline picture seems to have layers of white and black in some of the cliff faces – or even shades of kinds of layers. Some might be “snow” on the surface but some must therefore be “real” underneath stuff.

CratersandPlains oddly shows some craters layered with white presumably something snow-like(nitrogen frost? does nitrogen “frost”?) but others have black bottoms, or layers of black and white (even in the shadow side?) Could this be residual heat in some craters keeping a light dusting of nitrogen snow at bay?

Interesting to see that the region adjoining Sputnik planum is now thought to be a large collapse feature. I posted this idea on the Nature website in September and on FB, as it looked like the hummocky terrain around Mt Shasta or Mr St Helens, where large collapses are known to have occurred (1980 in the case of St Helens). I wonder if I’ll get credit on the paper… Presumably nitrogen or carbon monoxide fluids have undermined the basin walls causing them to progressively fail and slump intro the basin. I emailed this idea to John Spencer when the images came out. The region that was initially posited as dunes looks far more like soil creep seen on hillsides where the ground is sodden (in our case with water). It will be interesting to see what other analogues of terrestrial geology pop up on this frozen world.