Images and data are arriving from MESSENGER’s recent flyby of Mercury. Scientists from NASA and the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Lab are pouring over high resolution images of the side of the planet that has never before been imaged by a spacecraft. From these images, planetary geologists can study the processes that have shaped Mercury’s surface over the past 4 billion years. Let’s take a look at some of the images snapped by MESSENGER on January 14:

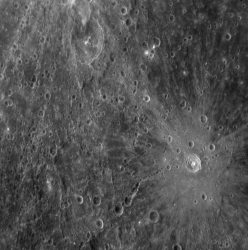

This image was taken just 21 minutes after MESSENGER’s closest approach to Mercury, at a distance of only 5,000 kilometers (3600 miles). It shows a region about 170 km (100 miles) across. Visible are a variety of surface features, including craters as small as about 300 meters (about 300 yards) across. But the most striking part of the image is one of the highest and longest cliffs yet seen on Mercury. About 80 km (50 miles) long, it curves from the bottom center up across the right side of this image. Scientists say that great forces in Mercury’s crust must have thrust the terrain occupying the left two-thirds of the picture up and over the terrain to the right. An impact crater has subsequently destroyed a small part of the cliff near the top of the image.

This image shows a previously unseen crater with distinctive bright rays of ejected material from the impact extending outward, providing a look at minerals from beneath Mercury’s surface. A chain of craters nearby is also visible. Studying impact craters provides insight into the history and composition of Mercury. The width of the image is about 370 kilometers (about 230 miles), and was taken about 37 minutes after MESSENGER’s closest approach. This image is the 98th in a set of 99 images that were taken to create a large, high-resolution mosaic of this region of Mercury. Hopefully this anticipated mosaic will be released at a planned press conference on January 30.

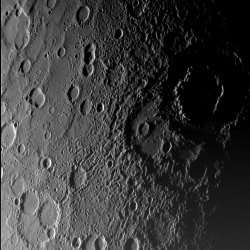

As MESSENGER approached Mercury on January 14, 2008, about 56 minutes before the spacecraft’s closest encounter, the Narrow-Angle Camera captured this view of the planet’s rugged, cratered landscape illuminated by the Sun. Although this crater has been imaged before by Mariner 10, MESSENGER’s modern camera has revealed detail that was not well seen by Mariner including the broad ancient depression overlapped by the lower-left part of the Vivaldi crater. Its outer ring has a diameter of about 200 kilometers (about 125 miles). The image shows an area about 500 km 9300 miles) across and craters as small as 1 kilometer (0.6 mile) can be seen. It was taken from a distance of about 18,000 km (11,000 miles.)

The MESSENGER (Mercury Surface Space Environment Geochemistry and Ranging) Science Team has begun analyzing these high-resolution images to unravel the history of Mercury, as well as the history of our solar system.

Original News Source: MESSENGER Website

Gld I found this sight. Booked to favorites .

I have been looking at the crater and surface images and am wondering if the sharply defined and deep crater rims indicate a lack of surface dust on Mercury. Is it possible that the extreme temperatures Mercury is subjected to in addition to the more powerful and hot solar wind are keeping dust at bay, or perhaps even fused to the surface?

Owlhoot Says:

“I have been looking at the crater and surface images and am wondering if the sharply defined and deep crater rims indicate a lack of surface dust on Mercury.”

No acid rock on Mercury,dude. Its all heavy metal.

Look at the pictures and think ‘molten solder’. Its more like splat rather than impact, eh.

Isn’t the reference to Mercury’s “Far Side” in the headline a misnomer — or at least an anarchonism? We’ve known that Mercury is not tidally locked to the Sun for quite a while.

[quote]No acid rock on Mercury,dude. Its all heavy metal.

Look at the pictures and think ‘molten solder’. Its more like splat rather than impact, eh.[end quote]

To Raving: Really? That would be interesting. if that’s the case, then perhaps Mercury should be explored for minerals and resources instead of the asteroid belt. 😉

I want to know from the wise guys, the reason why it is not tidally locked to the Sun, ?

Mercury was captured in a 3:2 resonance, it rotates 3 times for every two orbits. This resonance is stable due to the eccentricity of its orbit, e=0.2.