The first spacecraft to reach the surface of another world was the Soviet Venera 3 probe. Venera 3 crash-landed on the surface of Venus on March 1, 1966, 50 years ago. It was the 3rd in the series of Venera probes, but the first two never made it.

Venera 3 didn’t last long. It survived Venus’ blistering heat and crushing atmospheric pressure for only 57 minutes. But because of that 57 minutes, its place in history is cemented.

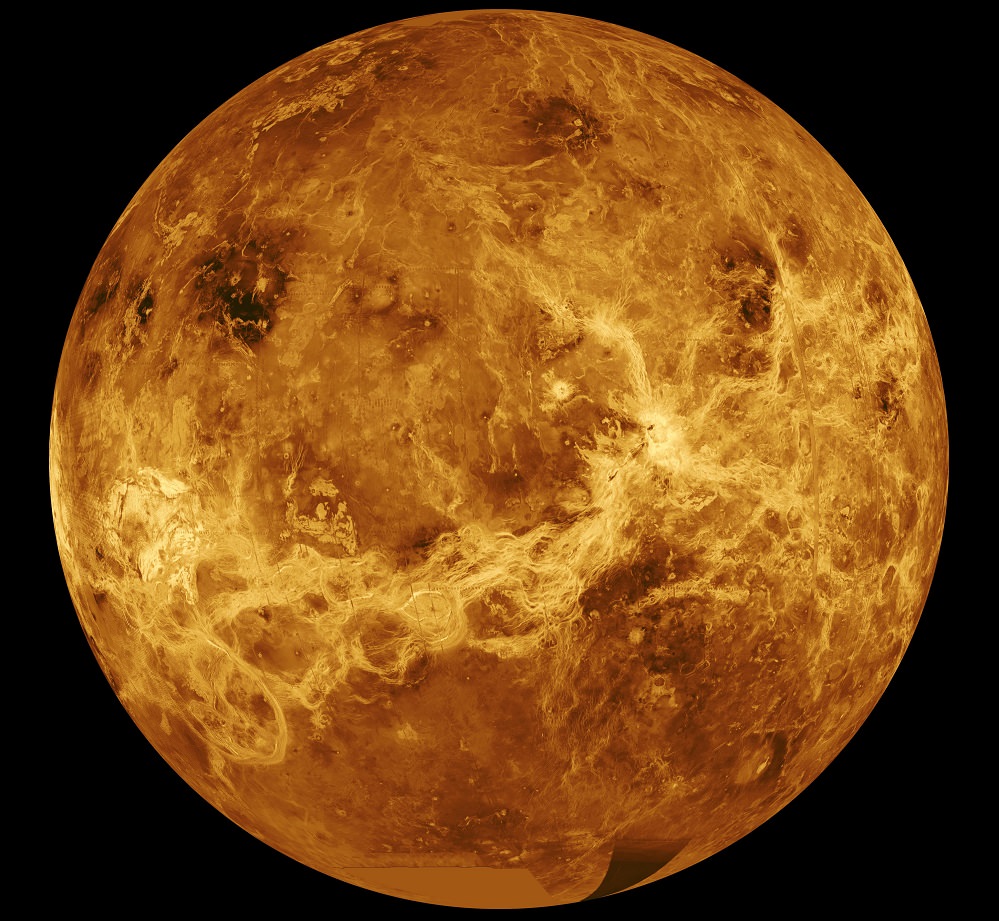

With a temperature of 462 degree C. (863 F.,) and a surface pressure 90 times greater than Earth’s, Venus’ atmosphere is the most hostile one in the Solar System. But Venus is still a tantalizing target for exploration, and rather than letting the difficult conditions deter them, Venus is a target that NASA thinks it can hit.

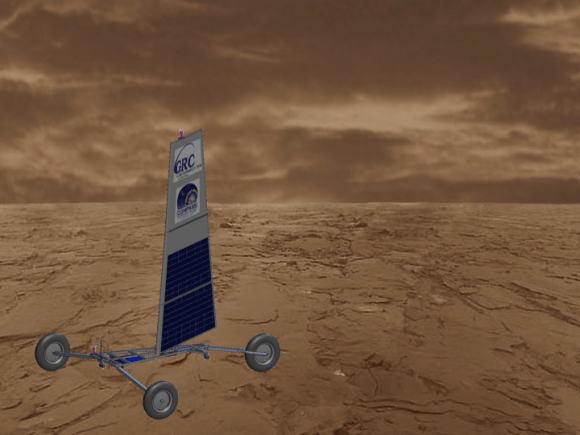

The Venus Landsail—called Zephyr—could be the first craft to survive the hostile environment on Venus. If approved, it would launch in 2023, and spend 50 days on the surface of Venus. But to do so, it has to meet several challenges.

NASA thinks they have the electronics that can withstand the heat, pressure, and corrosive atmosphere of Venus. Their development of sensors that can function inside jet engines proves this, and is the kind of breakthrough that really helps to advance space exploration. They also have solar cells that should function on the surface of Venus.

But the thick cloud cover will prevent the Zephyr’s solar cells from generating much electricity; certainly not enough for mobility. They needed another solution for traversing the surface of Venus: the land sail.

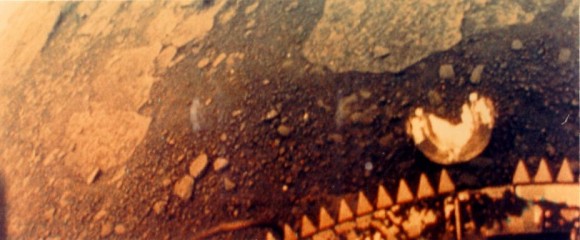

Venus has very slow winds—less than one meter per second—but the high density of the atmosphere means that even a slow wind will allow Zephyr to move effectively around the Venusian surface. But a land sail will only work on a surface without large rocks in the way. Thanks to the images of the surface of Venus sent back to Earth from the Venera probes, we know that a land sail will work, at least in some parts of the Venusian surface.

So Venus is back on the menu. With all the missions to other places in the Solar System, Venus is kind of forgotten, right here in our own backyard. But there’s actually a pretty rich history of missions to Venus, even though an extended visit to the surface has been out of reach. Since it’s been 50 years since Venera 3 reached the surface, now is a good time to look back at the history of the exploration of Venus.

The Soviet Union dominated the exploration of Venus. The Venera probes went all the way up to Venera 16, though some were orbiters rather than landers. From one perspective, the whole Venera program was plagued with problems. Many of the craft failed completely, or else had malfunctions that crippled them. But they still returned important information, and achieved many firsts, so the Venera program overall has to be considered a success.

The Soviet Union did not like to acknowledge or talk about space missions that failed. They often changed the name of a mission if it failed, so the names and numbers can get a little confusing.

Venera 4 was actually the first spacecraft to transmit any data from another world. On October 18th, 1967, it transmitted data from Venus’ atmosphere, but none from the surface. There were actually ten Venera missions before it, but most of them didn’t make it to Venus, suffering explosions or failing to leave Earth’s orbit and crashing back to the surface of Earth. Two of the Venera probes, numbers 1 and 2, suffered a loss of communications, so their fate is unknown.

After Venera 4’s relative success, there was another failed craft that fell back to Earth. Then on May 16th, 1969, Venera 5 successfully entered Venus’ atmosphere, and made it to within 26 kilometers of the surface before being crushed by the pressure. The next day—the Soviets often launched missions in pairs—Venera 6 entered the atmosphere of Venus and successfully transmitted data. It made it deeper into the atmosphere before being crushed within 11 kilometers of the surface.

Venera 7 was a successful mission. On December 15th, 1970, it landed on the surface of Venus and survived for 23 minutes. Venera 7 was the very first broadcast from the surface of another planet.

In 1972 Venera 8 survived for 50 minutes on the surface, followed by Venera 9 in 1975. Venera 9 survived for 53 minutes and sent back the first black and white images of the surface of Venus. Venera 10 landed 3 days after Venera 9 and survived 65 minutes, and also sent photos back. Grainy and blurry, but still amazing!

December 1978 saw the arrival of Venera 11 and 12, surviving 95 and 112 minutes respectively. Venera 11’s camera failed, but Venera 12 recorded what is thought to be lightning.

In March 1982, Venera 13 and 14 arrived. 13 took the first color images of the surface of Venus, and both craft took soil samples. Venera 15 and 16—both orbiters—arrived in 1983 and mapped the northern hemisphere.

The Soviet Unions final missions to Venus were Vega 1 and Vega 2, in 1985, which combined landings on Venus and flybys of Halley’s comet into each mission. Vega 1’s surface experiments failed, while Vega 2 transmitted data from the surface for 56 minutes.

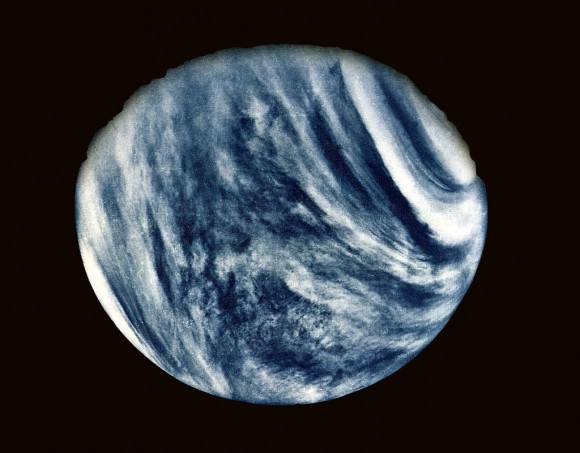

The United States has also launched several mission to Venus, though none have been landers. Spacecraft in the Mariner series studied Venus from orbit and during flybys, sometimes getting quite close to the cloud tops.

In 1962 and 1967, Mariner 2 and 5 completed flybys of Venus and transmitted data back to Earth. Mariner 5 came as close as 4094 km of the surface. In February 1974, Mariner 10 approached Venus and came to within 5,768 km. It returned color images of Venus, and then used gravitational assist—the first spacecraft to ever do so—to propel itself to Mercury.

In December 1978, the Pioneer Venus Orbiter reached Venus and studied the atmosphere, surface, and other aspects of Venus. It lasted until August 1992, when its fuel ran out and it was destroyed when it entered the atmosphere.

On August 1990, the Magellan mission reached Venus and used radar to map the surface of the planet. On October 1994, Magellan entered the Venusian atmosphere and was destroyed, but not before successfully mapping over 99% of the planet’s surface.

Messenger was a NASA mission to Mercury that was launched in August 2004. It did two flybys of Venus, in October 2006 and June 2007.

The Venus Express, a European Space Agency mission, orbited Venus and studied the atmosphere and plasma of Venus. Of special interest to Venus Express was the study of what role greenhouse gases played in the formation of the atmosphere.

In 2010, the Japanese Space Agency launched Akatsuki, also known as the Venus Climate Orbiter. It’s role is to orbit Venus and study the atmospheric dynamics. It will also look for evidence of lightning and volcanic activity.

If there’s one thing that space exploration keeps teaching us, it’s to expect the unexpected. Who knows what we’ll find on Venus, if the Land Sail mission is approved, and it survives for its projected 50 days.

OK it’s scientifically interesting but that’s the only driver for visiting. Venus just needs to be terraformed. If we can geneer extremophiles to split that much C02 then we need never worry about Terra, although spinning it up to a decent day rotation period is a bit more of a challenge.

Steve,

I’m not a Scientist by any means, and I’m not beating up on your post (especially considering were both just dreaming anyway). However, in my amateur quest for knowledge, and for conversation’s sake, I have to wonder why you think _Venus_ a good candidate for Terraformation (note: I may have totally made that word up) instead of _Mars_?

*Temperature wise only*- At certain times, a human could stand on Mars in a swimsuit and feel good (I *don’t* suggest trying this), whereas a human would boil away rather immediately at any point on Venus. Even at its coldest, a human could likely make a real quick 10 second dash outside in their bathrobe to grab their smokes out of their car without dying. On Venus though, not even one of those sweet baseball caps with the little battery powered fans attached to the brim would help you!!

Concerning atmosphere- While I’m not suggesting genetically _”engineering”_ (I’m highly suspicious that’s what you meant) Extremophiles which might reduce the thick and crushing atmosphere of Venus would be _impossible_ (I’m *very* underqualified to say), it seems that taking a problematically _thin_ atmosphere and making it thicker is something we’re… well, _hella_ good at already as the cool kids might say. We know how to produce atmospherically thickening gases with staggering efficiency (though not at a rate to create a sufficiently thick atmosphere on Mars in a few days or anything), whereas, we know little – maybe nothing – about _actually_ creating the Extremophiles you speak of (<<< correct me if I'm wrong on this please).

Access- We *currently* have the technology, if not the financial means, to land on Mars, build colonies, operate vehicles etc. Essentially, with our *current* tech, we could build an industrial habitat upon Mars within which we could create the products and complete the processes needed to terraform the _"Fire Star"_. The _"Morning Star"_ though, well that's more complicated. What with the pressures and temperatures at the surface, not to mention the need for a CPVC, or 316L stainless steel umbrella constantly. In fact, I'd venture to say, with our *current* technology – and even that which is foreseeable in the near future – it's not possible.

Mars has a nice axial tilt to create seasons, albeit longer ones than we're used to. Venus doesn't.

Mars has a nice length of day. Venus doesn't (which you mentioned.

Although, fixing both of the last issues is *super* easy. Bear in mind, I haven't _officially_ published my idea yet, but I personally purpose fixing both of the last issues by strapping a few rockets (i don't know- 3 maybe 4) to the now defeated, depressed, and useless Pluto, driving that bitch in to the inner SS, and slamming it into Venus at an angle to speed it up/tilt it!! Couldn't possibly go wrong as far as I can tell!

In all seriousness, why Venus over mars??

Is it the gravity you like?

The fact that it's closer?

That it's named after a hot chick instead of some A-hole war mongerer??

I don’t think it’s a question of Venus OR Mars. Why not both?

Your humorous idea of slamming Pluto into Venus at an oblique angle to spin Venus up is not entirely silly, except I would use a series of comets. Hit Venus at the right angle, and each comet can not only spin Venus up a bit but also splash off some of its atmosphere into space.

Hey Fraser,

You got a direct line to all our buddies at NASA right?

Do me a favor please… Send them a text message and tell them to put a damn camera on this one. A normal one. I’m sure there’s a high pressure housing for the newest GoPro available at Best Buy or something.

Hell, I’ll even donate it.

In all seriousness, I’m sure there’s a reason that most of the pictures we get from space are colored in weird wavelengths of light not visible to the human eye (probably because that’s what’s actually out there).

But, I’m sure there’s enough visible light on Venus. So, wanna get the public interested in space exploration again (I.e. Funding)?? Give them beautiful, color, HD images of the surface of this planet that they can see on their smartphones (The only thing most people care about exploring) and Tweet to each other and use for desktop wallpaper.

Then tack a few scientific thingy dingys on there too I guess…… But by and large, the public want PHOTOS of Venus, of the Galilean moons of Jupiter, of Mars, of everything!

May seem unimportant to science….. Until you consider that the young generation of Millennial’s will soon be in charge of NASA’s funding (or lack thereof)

So….. Tell them Dave said take a damn camera with them.

They can call with any questions. Thanks.

Check out the spec for the Venera 13& 14 probes, they had quartz lens cameras and titanium pressure vessels and lasted at best two hours, it’s gonna have to move very quick to get pictures of anything beyond its landing area.

Well,

Admittedly, I don’t know that much about it, probably less than you.

I just figured in my common sense, NON cosmolo-rocket-astro-scientist brain, that if they can – or think they can – get wheels with bearings to roll, a “sail” (of whatever material is used) solar panels (with whatever substitute they use for glass), and all the ostensibly super sensitive and probably intricate instruments and sensors, plus whatever transmitting system they use to get the data back to Earth, to all work correctly, without being crushed or destroyed by the acidic rain, pressure, temps etc. for FIFTY days, than they should be able to keep a color, HD camera working for a couple weeks (of course I was totally joking about an off the shelf GoPro or some such)

Does it have any scientific use? Well, I’d personally argue yes (although far less than the telemetry from all the sensors). But, even if the answer to that question is a solid “NO”, it still has massive value in my opinion.

It stimulates the intrinsic wonder of the human mind. It gets plastered in textbooks (or the modern iPad equivalent). It travels the internet and social media at light speed. It gets shown to billions of kids in classrooms, inspiring them far more effectively to take an interest in various space sciences than grainy, black and white Venera pictures do. In short, it makes at least a FEW more people take an interest in the exploration of our solar system/universe.

With NASA in particular being a publicly funded – or underfunded, even DE-funded for that matter – agency, those pictures could turn out to be a LOT of science gained…… Or, lost.

99% of humans are massively visual. Humans can think, be told, read, dream, imagine, and fully understand about sex, but their need to SEE it makes porn unbelievably successful (yeah, I know, REAL weird analogy, but the best I can think of at the moment)

And speaking of the Venera missions, that’s EXACTLY what I’m talking about! Granted, those pics (and I know it wasn’t 13 and 14) were taken when we had much lower tech, but regardless, the photos we got from it are like almost ALL photos we get from space (Hubble being a notable exception). Either black and white, or false color, or infrared, or a “mosaic” stitched together from 200 pictures, or (as with Venera), weird fisheye angles/aspects showing only a few rocks.

I obviously understand the need for infrared, microwave, whatever.. When looking at objects that can’t otherwise be seen by humans. I also understand that the Venera missions which were successful and brought us those “crappy” pictures were a MASSIVE achievement at the time….

But it’s now “our” time. So, having admitted several times that my knowledge does NOT extend nearly far enough to comprehend all the details, I just don’t understand why we couldn’t obtain some full color (assuming we’re on the day side) NORMAL ASPECT (not some weird fisheye, tiny, stitched together thing), true color photos of the Venetian surface for our $700 million (totally made up figure).

What am I misunderstanding?