It is known as the Cupola, an observation and work area that was installed aboard the International Space Station in 2010. In addition to giving the crew ample visibility to support the control of the Station’s robotic arms, it is also the best seat in the house when it comes to viewing Earth, celestial objects and visiting vehicles. Little wonder then why sp many breathtaking pictures have been taken from inside it over the years.

So you can imagine how frustrating it must be for the crew when a tiny artificial object (aka. space debris) collides with the Cupola’s windows and causes it to chip. And thanks to astronaut Tim Peake and a recent photo he chose to share with the world, people here on Earth are able to see just how this looks from the receiving end for the first time.

The picture was snapped last month, and shows a chip in the Cupola window that measures 7 mm in diameter. The crew speculate that it was most likely caused by the impact of a tiny piece of space debris, possibly a paint flake or small metal fragment. Though it would have been no bigger than a few thousandths of a millimeter across, the orbital velocity of debris and the ISS meant that when they struck, the impact was hard enough to leave a mark!

According to Peake, the picture was motivated in part by a question which – as an astronaut – he is routinely asked. “I am often asked if the International Space Station is hit by space debris,” he said. “Yes – this is the chip in one of our Cupola windows, glad it is quadruple glazed!”

In other words, there was no threat of decompression from this chip in the window. Still, I’m betting that it’s times like these that the ISS wishes there was such a thing as orbital window insurance! And while the chip shown in the pictures was minor in nature, larger debris can pose a serious threat to orbiting labs and spaceships.

An object up to 1 cm in size – which by definition falls into the category of a meteoroid – could disable an instrument or a critical flight system aboard the ISS or anything else in orbit of Earth. Something larger than 1 cm could penetrate the shields on the Station’s crew modules, leading to dangerous decompression. And anything larger than 10 cm, could literally destroy the ISS.

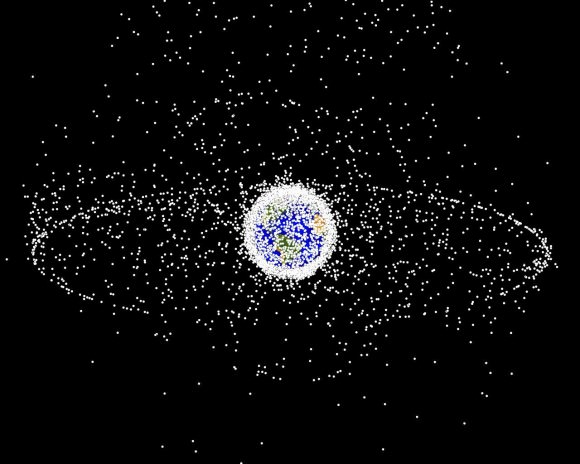

And given it position in Low Earth Orbit (LEO), the threat of space debris, which comes in all forms – spent rocket stages, satellites that are no longer in use, paint flakes, metal fragments, and natural meteoroids and micrometeoroids – are a significant threat. In fact, it was estimated in 2013 that more than 500,000 pieces of debris – which travel at speeds up to 28,164 km/h (17,500 mph) – were being tracked as they orbited the Earth.

However, NASA, the ESA, Roscosmos and other space agencies routinely monitor Earth’s orbit to determine if there’s any potential for collisions between the ISS and large pieces of space junk. The station itself is also protected by layers of shielding designed to withstand collisions with smaller ones, so there is little chance the station and its crews are ever threatened.

The larger objects in LEO are less of a threat because their orbits can be predicted, and these are tracked remotely from the ground. This allows the crews to conduct Debris Avoidance Maneuvers (DAMs), which uses thrusters on the Russian Orbital Segment to alter the station’s orbital altitude. The ISS performed eight DAMs between Oct 1999 and March 2009, and another two between late March and mid-July of 2009.

In the event where a potential threat was identified too late to conduct a DAM, the crews close all the hatches aboard the station and retreat into their Soyuz spacecraft (or whichever module is currently docked) so they may evacuate if a serious collision occurs. Such partial evacuations have been conducted four times in the station’s history, between March 2009 and June 2015.

As for objects that are too small to track, the station relies on shielding, which is divided between the Russian Orbital Segment (ROS) and the US Orbital Segment (USOS). The USOS is protected by a thin aluminum sheet space from the hull. This shield causes objects to shatter into a cloud before hitting the hull, thereby spreading the energy of the impact.

The ROS, meanwhile, is protected by a carbon plastic honeycomb screen, an aluminum honeycomb and a glass cloth cover, all of which are separated from the hull by a screen-vacuum thermal insulation covering. The ROS’ shielding is about 50% less likely to be punctured, which is why the crew move to the ROS whenever the station is under threat. The ISS also relies on ballistic panels (aka. “micrometeorite shielding) to protect pressurized sections and critical systems.

And of course, the ESA chose to take this occasion to remind everyone that with this and other impacts, they are on top of things. As Holger Krag, Head of ESA’s Space Debris Office said in a recent statement:

“[The] ESA is at the forefront of developing and implementing debris-mitigation guidelines, because the best way to avoid problems from orbital debris is not to cause them in the first place. These guidelines are applied to all new missions flown by ESA, and include dumping fuel tanks and discharging batteries at the end of a mission, to avoid explosions, and ensuring that satellites reenter the atmosphere and safely burn up within 25 years of the end of their working lives.”

The Cupola is also where ESA’s Nightpod camera aid is installed to help astronauts take sharper pictures at night. Over the years, this has allowed for some of the most breathtaking photos of Earth from orbit to be snapped. You can check some of them out at the Space in Images section of the ESA’s website. And in the meantime, it not be too soon to start contemplating insurance for orbital habitats!

Further Reading: ESA- Space in Images

They actually sell insurance for that sort of damage?

Not to my knowledge, no. That was just a little joke. But it seems like a good idea, seeing as how the presence of humans in orbit is likely to become more common.

I could sell you a policy

A 10 cm object … it seems like it would just pass right through and retain most of its momentum. Like shooting a beer can with a .22

I wonder if anyone is working on a self-healing membrane that forms a clot when punctured. Or even better, a living space station with circulatory system, light harvesting plastids, and, naturally, fermentable fruit juice on tap. ” Rotate the Pods please, Kale.” heh.

That escalated quicky into a wine.

Which kind of wine? A Shiraz or a Riesling? And I’m not even going to touch “quicky”! 😉

bro do you even edit?