Launching back in 2011, NASA’s Juno mission has spent the past five years traversing the gulf that lies between Earth and Jupiter. When it arrives (in just a few days time!), it will be the second long-term mission to the gas giant in history. And in the process, it will obtain information about its composition, weather patterns, magnetic and gravitational fields, and history of formation.

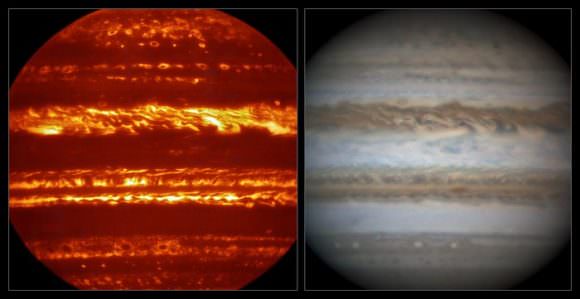

With just days to go before this historic rendezvous takes place, the European Southern Observatory is taking the opportunity to release some spectacular infrared images of Jupiter. Taken with the Very Large Telescope (VLT), these images are part of a campaign to create high-resolutions maps of the planet, and provide a preview of the work that Juno will be doing in the coming months.

Using the VTL Imager and Spectrometer for mid-Infrared (VISIR) instrument, the ESO team – led by Dr. Leigh Fletcher of the University of Leicester – hopes that their efforts to map the planet will improve our understanding of Jupiter’s atmosphere. Naturally, with the upcoming arrival of Juno, some may wonder if these efforts are necessary.

After all, ground-based telescopes like the VLT are forced to contend with limitations that space-based probes are not. These include interference from our constantly-shifting atmosphere, not to mention the distances between Earth and the object in question. But in truth, the Juno mission and ground-based campaigns like these are often highly complimentary.

For one, in the past few months, while Juno was nearing in on its destination, Jupiter’s atmosphere has undergone some significant shifts. Mapping these is important to Juno‘s upcoming arrival, at which point it will be attempting to peer beneath Jupiter’s thick clouds to discern what is going on beneath. In short, the more we know about Jupiter’s shifting atmosphere, the easier it will be to interpret the Juno data.

As Dr. Fletcher described the significance of his team’s efforts:

“These maps will help set the scene for what Juno will witness in the coming months. Observations at different wavelengths across the infrared spectrum allow us to piece together a three-dimensional picture of how energy and material are transported upwards through the atmosphere.”

Like all ground-based efforts, the ESO campaign – which has involved the use of several telescopes based in Hawaii and Chile, as well as contributions from amateur astronomers around the world – faced some serious challenges (like the aforementioned interference). However, the team used a technique known as “lucky imaging” to take the breathtaking snapshots of Jupiter’s turbulent atmosphere.

What this comes down to is taking many sequences of images with very short exposures, thus producing thousands of individual frames. The lucky frames, those where the image are least affected by the atmosphere’s turbulence, are then selected while the rest discarded. These selected frames are aligned and combined to produce final pictures, like the one shown above.

In addition to providing information that would be of use to the Juno mission, the ESO’s campaign has value that extends beyond the space-based mission. As Glenn Orton, the leader of ESO’s ground-based campaign, explained, observations like these are valuable because they help to advance our understanding of planets as a whole, and provide opportunities for astronomers from all over the world to collaborate.

“The combined efforts of an international team of amateur and professional astronomers have provided us with an incredibly rich dataset over the past eight months,” he said. “Together with the new results from Juno, the VISIR dataset in particular will allow researchers to characterize Jupiter’s global thermal structure, cloud cover and distribution of gaseous species.”

The Juno probe will be arriving at Jupiter this coming Monday, July 4th. Once there, it will spend the next two years orbiting the gas giant, sending information back to Earth that will help to advance our understanding of not only Jupiter, but the history of the Solar System as well.

Further Reading: ESO

I’m still blown away by the imaging techniques we’re using to get closer and closer to the theoretical/mathematical limits of what’s possible from the ground. The fact that this infrared image rivals ANY optical image beyond binoculars is just mind-melting.

So there’s your next hit of “Jovian-ly awesome,” served up days before we even get to see what Juno may have for us!

I’m thinking this IR image might influence future “artist’s impressions” of brown dwarfs and hot jupiters.