After a nearly 5 year odyssey across the solar system, NASA’s solar powered Juno orbiter is all set to ignite its main engine late tonight and set off a powerful charge of do-or-die fireworks on America’s ‘Independence Day’ required to place the probe into orbit around Jupiter – the ‘King of the Planets.’

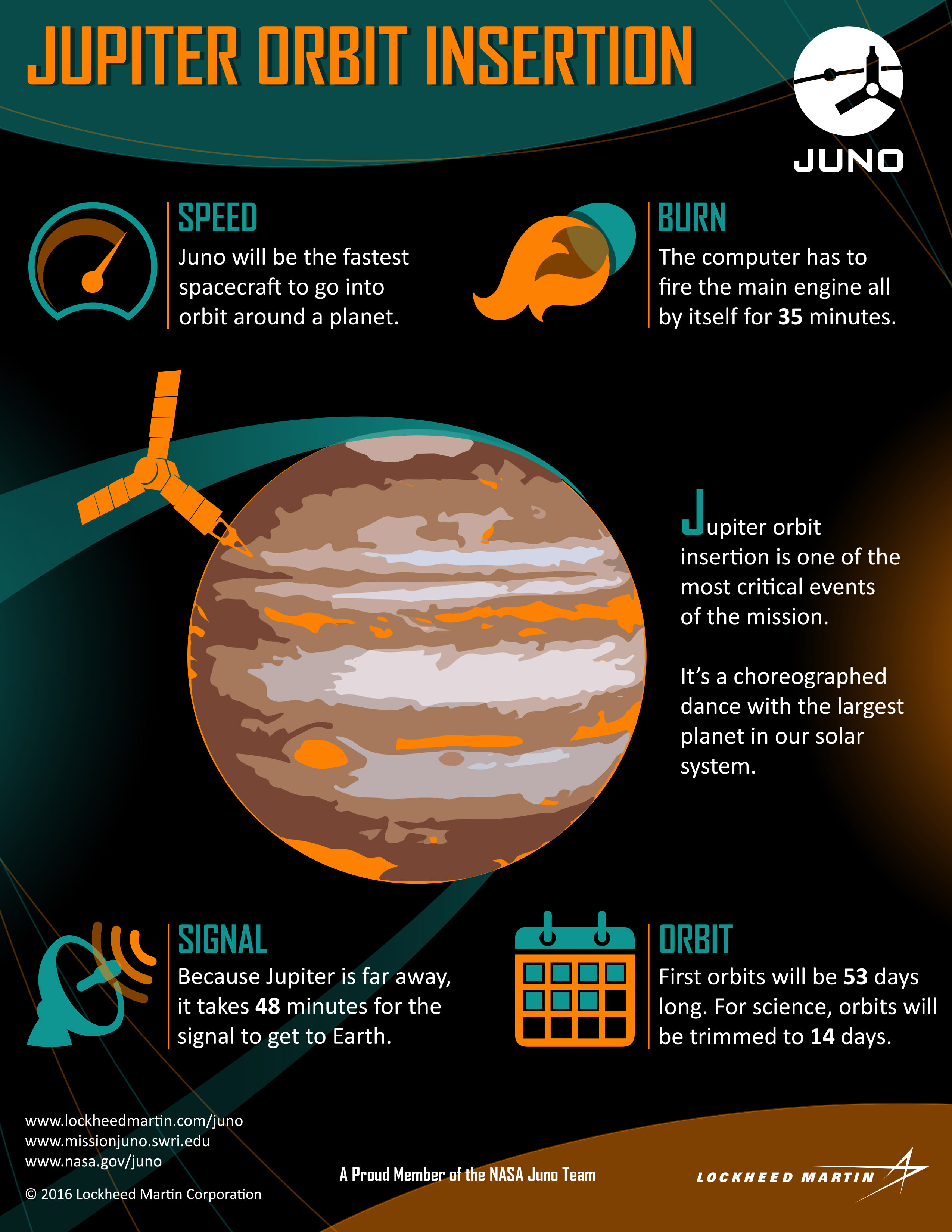

To achieve orbit, Juno must will perform a suspenseful maneuver known as ‘Jupiter Orbit Insertion’ or JOI tonight, Monday, July 4, upon which the entire mission and its fundamental science hinges. There are no second chances!

You can be part of all the excitement and tension building up to and during that moment, which is just hours away – and experience the ‘Joy of JOI’ by tuning into NASA TV tonight!

Watch the live webcast on NASA TV featuring the top scientists and NASA officials starting at 10:30 p.m. EDT (7:30 p.m. PST, 0230 GMT) – direct from NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory: https://www.nasa.gov/nasatv

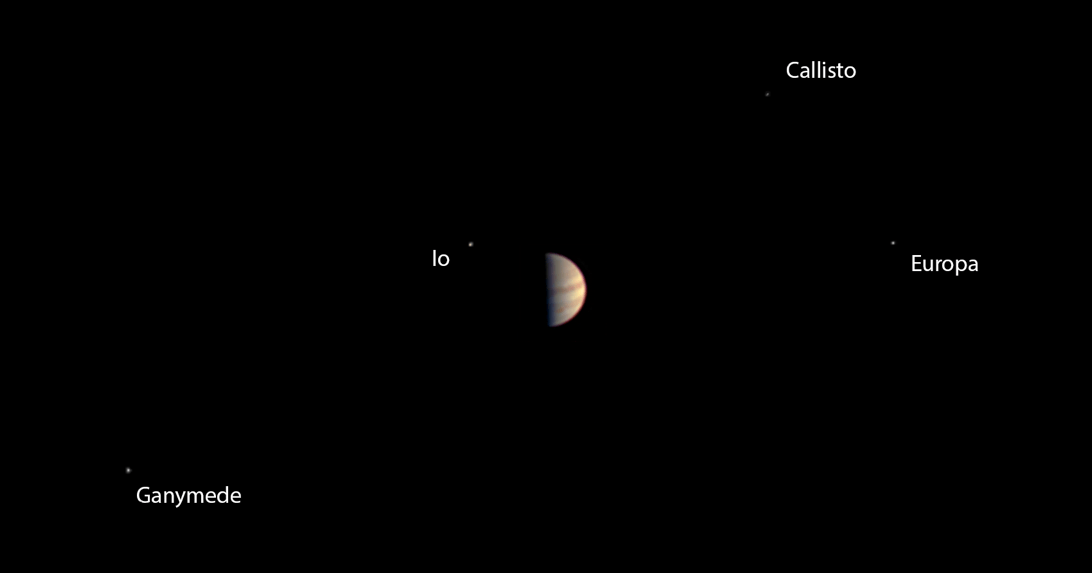

And for a breathtaking warm-up act, Juno’s on board public outreach JunoCam camera snapped a final gorgeous view of the Jovian system showing Jupiter and its four largest moons, dancing around the largest planet in our solar system.

The newly released color image was taken on June 29, 2016, at a distance of 3.3 million miles (5.3 million kilometers) from Jupiter – just before the probe went into autopilot mode.

It shows a dramatic view of the clouds bands of Jupiter, dominating a spectacular scene that includes the giant planet’s four largest moons — Io, Europa, Ganymede and Callisto.

NASA also released this new time-lapse JunoCam movie today:

Video caption: Juno’s Approach to Jupiter: After nearly five years traveling through space to its destination, NASA’s Juno spacecraft will arrive in orbit around Jupiter on July 4, 2016. This video shows a peek of what the spacecraft saw as it closed in on its destination. Credits: NASA/JPL-Caltech/MSSS

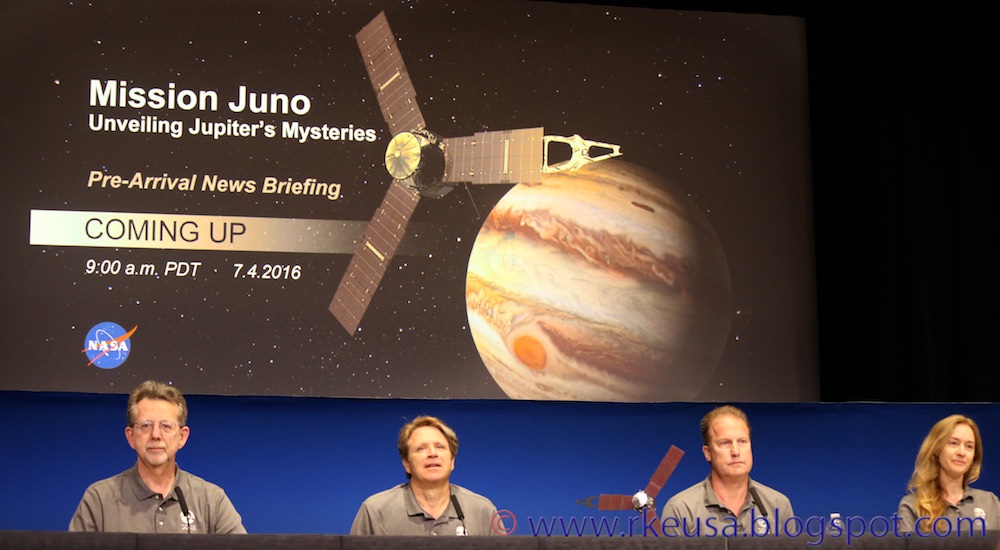

The spacecraft is approaching Jupiter over its north pole, affording an unprecedented perspective on the Jovian system – “which looks like a mini solar system,” said Juno Principal Investigator and chief scientist Scott Bolton, from the Southwest Research Institute (SwRI) in San Antonio, Tx, at today’s media briefing at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, Calif.

“The deep interior of Jupiter is nearly unknown. That’s what we are trying to learn about.”

The 35-minute-long main engine burn is preprogrammed to start at 11:18 p.m. EDT (8:18 p.m. PST, 0318 GMT). It is scheduled to last until approximately 11:53 p.m. (8:53 p.m. PST, 0353 GMT).

All of the science instruments were turned off on June 30 to keep the focus on the nail-biting insertion maneuver and preserve battery power, said Bolton. Solar powered Juno is pointed away from the sun during the engine firing.

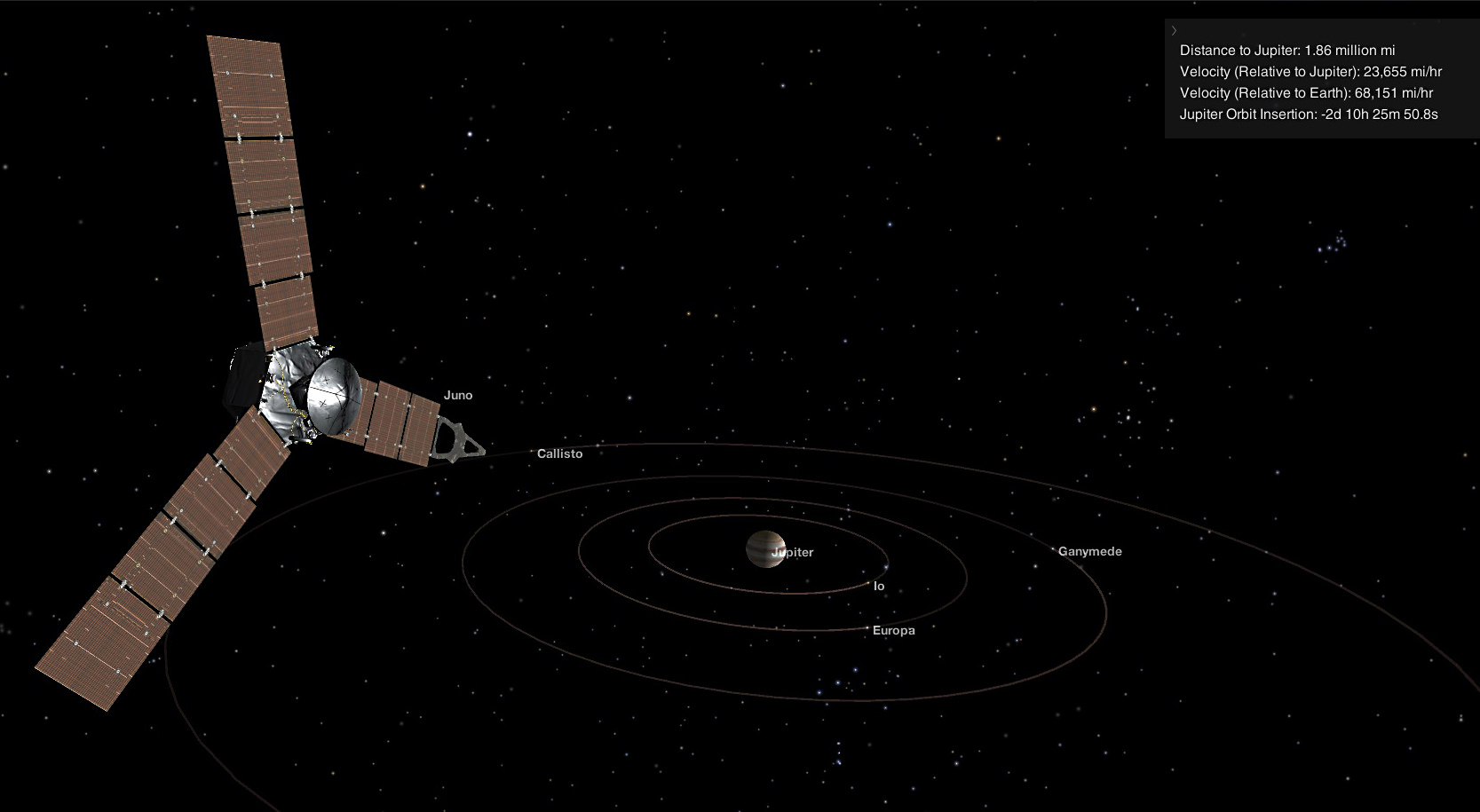

JOI is required to slow the spacecraft so it can be captured into the gas giant’s orbit as it closes in over the north pole.

Initially the spacecraft will enter a long, looping polar orbit lasting about 53 days. That highly elliptical orbit will quickly be trimmed to 14 days for the science orbits.

The orbits are designed to minimize contact with Jupiter’s extremely intense radiation belts. The science instruments are shielded inside a ½ thick vault built of Titanium to protect them from the utterly deadly radiation – of some 20,000,000 rads.

Credits: NASA/JPL-Caltech

Juno is the fastest spacecraft ever to arrive at Jupiter and is moving at over 165,000 mph relative to Earth and 130,000 mph relative to Jupiter.

After a five-year and 2.8 Billion kilometer (1.7 Billion mile) outbound trek to the Jovian system and the largest planet in our solar system and an intervening Earth flyby speed boost, the moment of truth for Juno is now inexorably at hand.

Signals traveling at the speed of light take 48 minutes to reach Earth, said Rick Nybakken, Juno project manager from NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, at the media briefing.

So the main engine burn, which is fully automated, will already be over for some 13 minutes before the first indications of the outcome reach Earth via a series of Doppler shifts and tones. It is about 540 million miles (869 million kilometers) from Earth.

“By the time the burn is complete, we won’t even hear about it until 13 minutes later.”

“The engine burn will slow Juno by 542 meters/second (1,212 mph) and is fully automated as it approaches over Jupiter’s North Pole,” explained Nybakken.

“The long five year cruise enabled us to really learn about the spacecraft and how it operates.”

As it travels through space, the basketball court sized Juno is spinning like a windmill with its 3 giant solar arrays.

“Juno is also the farthest mission to rely on solar power. The solar panels are 60 square meters in size. And although they provide only 1/25th the power at Earth, they still provide over 500 watts of power at Jupiter.”

The protective cover that shields Juno’s main engine from micrometeorites and interstellar dust was opened on June 20.

During a 20 month long science mission – entailing 37 orbits lasting 14 days each – the probe will plunge to within about 3000 miles of the turbulent cloud tops and collect unprecedented new data that will unveil the hidden inner secrets of Jupiter’s origin and evolution.

“Jupiter is the Rosetta Stone of our solar system,” says Bolton. “It is by far the oldest planet, contains more material than all the other planets, asteroids and comets combined and carries deep inside it the story of not only the solar system but of us. Juno is going there as our emissary — to interpret what Jupiter has to say.”

During the orbits, Juno will probe beneath the obscuring cloud cover of Jupiter and study its auroras to learn more about the planet’s origins, structure, atmosphere and magnetosphere.

The $1.1 Billion Juno was launched on Aug. 5, 2011 from Cape Canaveral, Florida atop the most powerful version of the Atlas V rocket augmented by 5 solid rocket boosters and built by United Launch Alliance (ULA). That same Atlas V 551 version just launched MUOS-5 for the US Navy on June 24.

The Juno spacecraft was built by prime contractor Lockheed Martin in Denver.

Along the way Juno made a return trip to Earth on Oct. 9, 2013 for a flyby gravity assist speed boost that enabled the trek to Jupiter.

The flyby provided 70% of the velocity compared to the Atlas V launch, said Nybakken.

During the Earth flyby (EFB), the science team observed Earth using most of Juno’s nine science instruments since the slingshot also serves as an important dress rehearsal and key test of the spacecraft’s instruments, systems and flight operations teams.

Juno also went into safe mode – something the team must avoid during JOI.

What lessons were learned from the safe mode event and applied to JOI, I asked?

“We had the battery at 50% state of charge during the EFB and didn’t accurately predict the sag on the battery when we went into eclipse. We now have a validated high fidelity power model which would have predicted that sag and we would have increased the battery voltage,” Nybakken told Universe Today

“It will not happen at JOI as we don’t go into eclipse and are at 100% SOC. Plus the instruments are off which increases our power margins.”

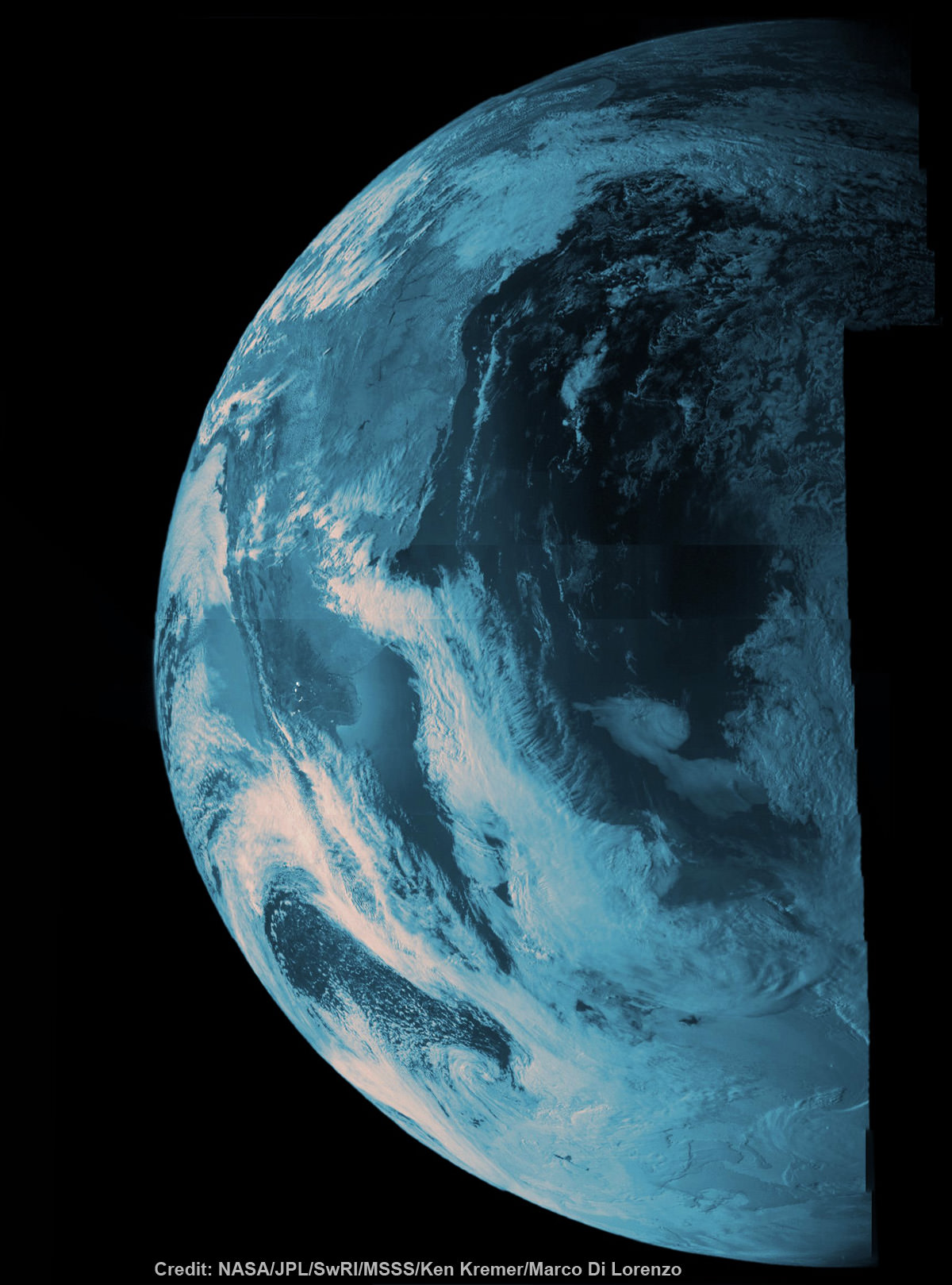

Junocam also took some striking images of Earth as it sped over Argentina, South America and the South Atlantic Ocean and came within 347 miles (560 kilometers) of the surface.

For example the dazzling portrait of our Home Planet high over the South American coastline and the Atlantic Ocean.

For a hint of what’s to come, see our colorized Junocam mosaic of land, sea and swirling clouds, created by Ken Kremer and Marco Di Lorenzo

The last NASA spacecraft to orbit Jupiter was Galileo in 1995. It explored the Jovian system until 2003.

Stay tuned here for Ken’s continuing Earth and Planetary science and human spaceflight news.

“Jupiter … is by far the oldest planet” — General histories of the solar system say it all formed around 5 billion years ago. I get that Jupiter, being larger, might have been around longer as a recognizable planet (big, round, etc.) — How *much* longer are we talking about? Are we talking millions of years? Tens or hundreds?