Welcome to Jupiter! NASA’s Juno spacecraft is orbiting Jupiter at this moment!

“NASA did it again!” pronounced an elated Scott Bolton, investigator of Juno from Southwest Research Institute in San Antonio, to loud cheers and applause from the overflow crowd of mission scientists and media gathered at the post orbit media briefing at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, Calif.

After a nearly five year journey covering 1.7-billion-miles (2.8-billion-kilometers) across our solar system, NASA’s basketball court-sized Juno orbiter achieved orbit around Jupiter, the ‘King of the Planets’ late Monday night, July 4, in a gift to all Americans on our 240th Independence Day and a gift to science to elucidate our origins.

“We are in orbit and now the fun begins, the science,” said Bolton at the briefing. “We just did the hardest thing NASA’s ever done! That’s my claim. I am so happy … and proud of this team.”

And the science is all about peering far beneath the well known banded cloud tops for the first time to investigate Jupiter’s deep interior with a suite of nine instruments, and discover the mysteries of its genesis and evolution and the implications for how we came to be.

“The deep interior of Jupiter is nearly unknown. That’s what we are trying to learn about. The origin of us.”

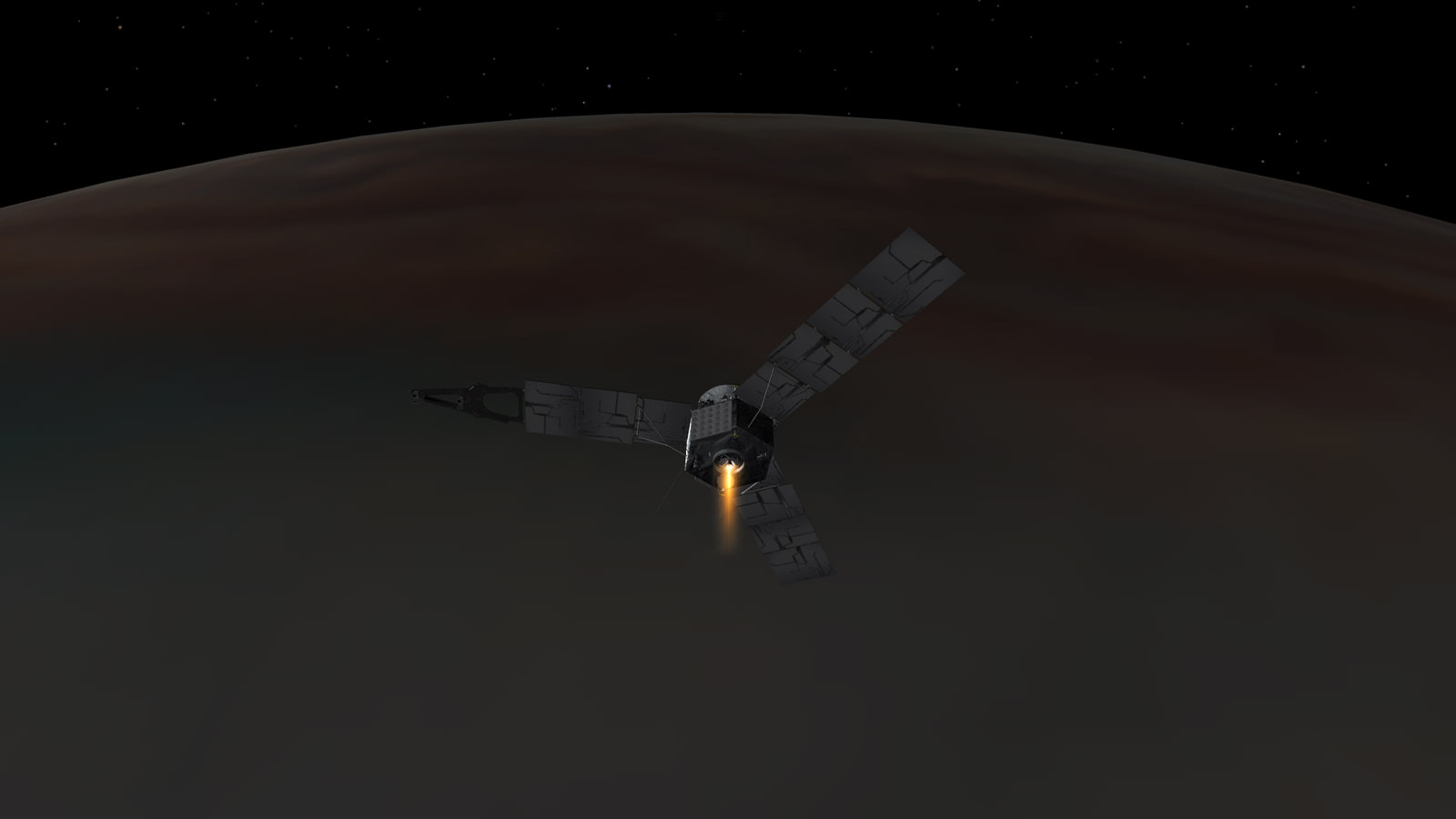

Solar powered Juno successfully entered a polar elliptical orbit around Jupiter after completing a must-do 35-minute-long firing of the main engine known as Jupiter Orbital Insertion or JOI.

The spacecraft approached Jupiter over its north pole, affording an unprecedented perspective on the Jovian system – “which looks like a mini solar system” – as it flew through the giant planets intense radiation belts in ‘autopilot’ mode.

“The mission team did great. The spacecraft did great. We are looking great. It’s a great day,” Bolton gushes.

Engineers tracking the telemetry received confirmation that the JOI burn was completed as planned at 8:53 p.m. PDT (11:53 p.m. EDT) Monday, July 4.

Juno is only the second probe from Earth to orbit Jupiter and the first solar powered probe to the outer planets. The gas giant is two and a half times more massive than all of the other planets combined.

“Independence Day always is something to celebrate, but today we can add to America’s birthday another reason to cheer — Juno is at Jupiter,” said NASA administrator Charlie Bolden in a statement.

“And what is more American than a NASA mission going boldly where no spacecraft has gone before? With Juno, we will investigate the unknowns of Jupiter’s massive radiation belts to delve deep into not only the planet’s interior, but into how Jupiter was born and how our entire solar system evolved.”

The do-or-die burn of Juno’s 645-Newton Leros-1b main engine started at 8:18 p.m. PDT (11:18 p.m. EDT), which had the effect of decreasing the spacecraft’s velocity by 1,212 miles per hour (542 meters per second) and allowing Juno to be captured in orbit around Jupiter. There were no second chances.

All of the science instruments were turned off on June 30 to keep the focus on the nail-biting insertion maneuver and preserve battery power, said Bolton.

“So tonight through tones Juno sang to us. And it was a song of perfection. After a 1.7 billion mile journey we hit tour burn targets within one second,” Rick Nybakken, Juno project manager from JPL, gleefully reported at the briefing.

“That’s how good our team is! And that’s how well our Juno spacecraft performed tonight.”

To accomplish the burn, the spacecraft first had to adjust it’s attitude to point the engine in the required direction to slow the spacecraft and then simultaneously also had the effect that the life giving solar panels were pointing away from the sun. It the only time during the entire mission at Jupiter that the solar panels were in darkness and not producing energy.

The spacecraft’s rotation rate was also spun up from 2 to 5 revolutions per minute (RPM) to help stabilize it during JOI. Juno is spin stabilized to maintain pointing.

After the burn was complete, Juno was spun down and adjusted to point to the sun before it ran out of battery power.

We have to get the blood flowing through Juno’s veins, Bolton emphasized.

It is equipped with 18,698 individual solar cells over 60 square meters of surface on the solar arrays to provide energy. Juno is spinning like a windmill through space with its 3 giant solar arrays. It is about 540 million miles (869 million kilometers) from Earth.

Signals traveling at the speed of light take 48 minutes to reach Earth, said Nybakken.

So the main engine burn, which was fully automated, was already over for some 13 minutes before the first indications of the outcome reach Earth via a series of Doppler signals and tones.

“Tonight, 540 million miles away, Juno performed a precisely choreographed dance at blazing speeds with the largest, most intense planet in our solar system,” said Guy Beutelschies, director of Interplanetary Missions at Lockheed Martin Space Systems.

“Since launch, Juno has operated exceptionally well, and the flawless orbit insertion is a testament to everyone working on Juno and their focus on getting this amazing spacecraft to its destination. NASA now has a science laboratory orbiting Jupiter.”

“The spacecraft is now pointed back at the sun and the antenna back at Earth. The spacecraft performed well and did everything it needed to do,” he reported at the briefing.

“We are looking forward to getting all that science data to Scott and the team.”

“Juno is also the farthest mission to rely on solar power. And although they provide only 1/25th the power at Earth, they still provide over 500 watts of power at Jupiter,” said Nybakken.

Initially the spacecraft enters a long, looping polar orbit lasting about 53 days. That highly elliptical orbit will be trimmed to 14 days for the regular science orbits.

The orbits are designed to minimize contact with Jupiter’s extremely intense radiation belts. The nine science instruments are shielded inside a ½ thick vault built of Titanium to protect them from the utterly deadly radiation of some 20,000,000 rads.

During a 20 month long science mission – entailing 37 orbits lasting 14 days each – the probe will plunge to within about 3000 miles of the turbulent cloud tops and collect unprecedented new data that will unveil the hidden inner secrets of Jupiter’s origin and evolution.

But the length and number of the science orbits has changed since the mission was launched almost 5 years ago in 2011.

Originally Juno was planned to last about one year with an orbital profile involving 33 orbits of 11 days each.

I asked the team to explain the details of how and why the change from 11 to 14 days orbits and increasing the total number of orbits to 37 from 33, especially in light of the extremely harsh radiation hazards?

“The original plan of 33 orbits of 11 days was an example but there were other periods that would work,” Bolton told Universe Today.

“What we really cared about was dropping down over the poles and capturing each longitude, and laying a map or net around Jupiter.”

“Also, during the Earth flyby we went into safe mode. And as we looked at that it was a hiccup by the spacecraft but it actually behaved as it should have.”

“So we said well if that happened at Jupiter we would like to be able to recover and not lose an orbit. So we started to look at the timeline of how long it took to recover, and did we want to add a couple of days to the orbit for conservatism – to ensure the science mission.”

“So it made sense to add 3 days. It didn’t change the science and it made the probability of success even greater. So that was the basis of the change.”

“We also evaluated the radiation. And it wasn’t much different. Juno is designed to take data at a very low risk. The radiation slowly accumulates at the start. As you get to the later part of the mission, it gets a faster and faster accumulation.”

“So we still retained that conservatism as well and the overall radiation dose was pretty much the same,” Bolton explained.

“The radiation we accumulate is not just the more time you spend the more radiation,” Steve Levin, Juno Project Scientist at JPL, told Universe Today.

“Each time we come in close to the planet we get a dose of radiation. Then the spacecraft is out far from Jupiter and is relatively free from that radiation until we come in close again.”

“So just changing from 11 to 14 day orbits does not mean we get more radiation because you are there longer.”

“It’s really the number of times we come in close to Jupiter that determines how much radiation we are getting.”

Juno is the fastest spacecraft ever to arrive at Jupiter and was moving at over 165,000 mph relative to Earth and 130,000 mph relative to Jupiter at the moment of JOI.

Juno’s principal goal is to understand the origin and evolution of Jupiter.

“With its suite of nine science instruments, Juno will investigate the existence of a solid planetary core, map Jupiter’s intense magnetic field, measure the amount of water and ammonia in the deep atmosphere, and observe the planet’s auroras. The mission also will let us take a giant step forward in our understanding of how giant planets form and the role these titans played in putting together the rest of the solar system. As our primary example of a giant planet, Jupiter also can provide critical knowledge for understanding the planetary systems being discovered around other stars,” according to a NASA description.

The $1.1 Billion Juno was launched on Aug. 5, 2011 from Cape Canaveral, Florida atop the most powerful version of the Atlas V rocket augmented by 5 solid rocket boosters and built by United Launch Alliance (ULA). That same Atlas V 551 version just launched MUOS-5 for the US Navy on June 24.

The Juno spacecraft was built by prime contractor Lockheed Martin in Denver.

The last NASA spacecraft to orbit Jupiter was Galileo in 1995. It explored the Jovian system until 2003.

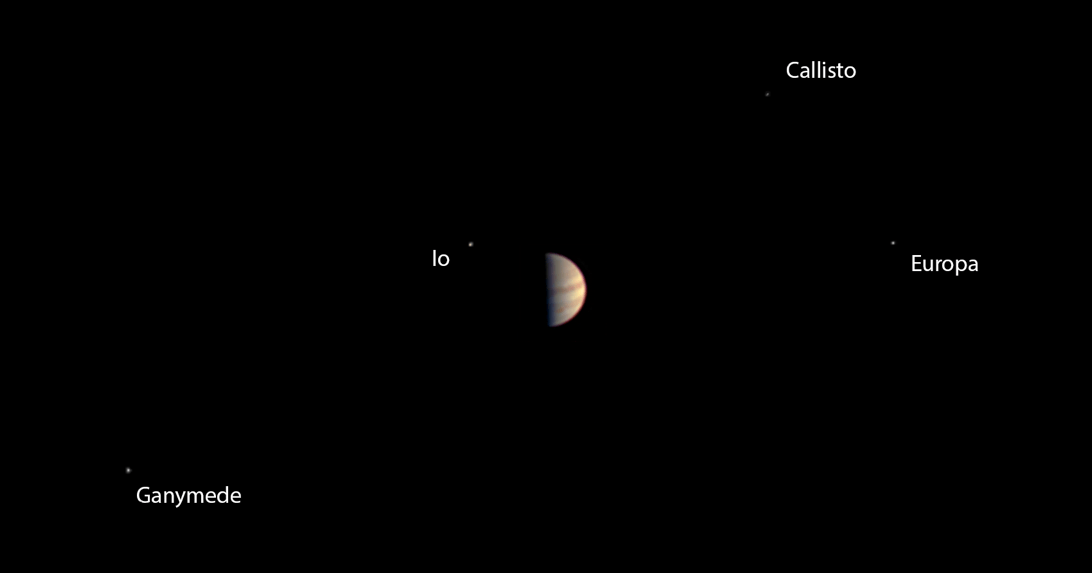

Bolton also released new views of Jupiter taken by JunoCam – the on board public outreach camera that snapped a final gorgeous view of the Jovian system showing Jupiter and its four largest moons, dancing around the largest planet in our solar system.

The newly released color image was taken on June 29, 2016, at a distance of 3.3 million miles (5.3 million kilometers) from Jupiter – just before the probe went into autopilot mode.

It shows a dramatic view of the clouds bands of Jupiter, dominating a spectacular scene that includes the giant planet’s four largest moons — Io, Europa, Ganymede and Callisto.

Scott Bolton and NASA also released this spectacular new time-lapse JunoCam movie at today’s briefing showing Juno’s approach to Jupiter and the Galilean Moons.

Watch and be mesmerized -“for humanity, our first real glimpse of celestial harmonic motion” says Bolton.

Video caption: NASA’s Juno spacecraft captured a unique time-lapse movie of the Galilean satellites in motion about Jupiter. The movie begins on June 12th with Juno 10 million miles from Jupiter, and ends on June 29th, 3 million miles distant. The innermost moon is volcanic Io; next in line is the ice-crusted ocean world Europa, followed by massive Ganymede, and finally, heavily cratered Callisto. Galileo observed these moons change position with respect to Jupiter over the course of a few nights. From this observation he realized that the moons were orbiting mighty Jupiter, a truth that forever changed humanity’s understanding of our place in the cosmos. Earth was not the center of the Universe. For the first time in history, we look upon these moons as they orbit Jupiter and share in Galileo’s revelation. This is the motion of nature’s harmony. Credits: NASA/JPL-Caltech/MSSS

Along the 5 year journey to Jupiter, Juno made a return trip to Earth on Oct. 9, 2013 for a flyby gravity assist speed boost that enabled the trek to the Jovian system.

During the Earth flyby (EFB), the science team observed Earth using most of Juno’s nine science instruments including, JunoCam, since the slingshot also served as an important dress rehearsal and key test of the spacecraft’s instruments, systems and flight operations teams.

The JunoCam images will be made publicly available to see and process.

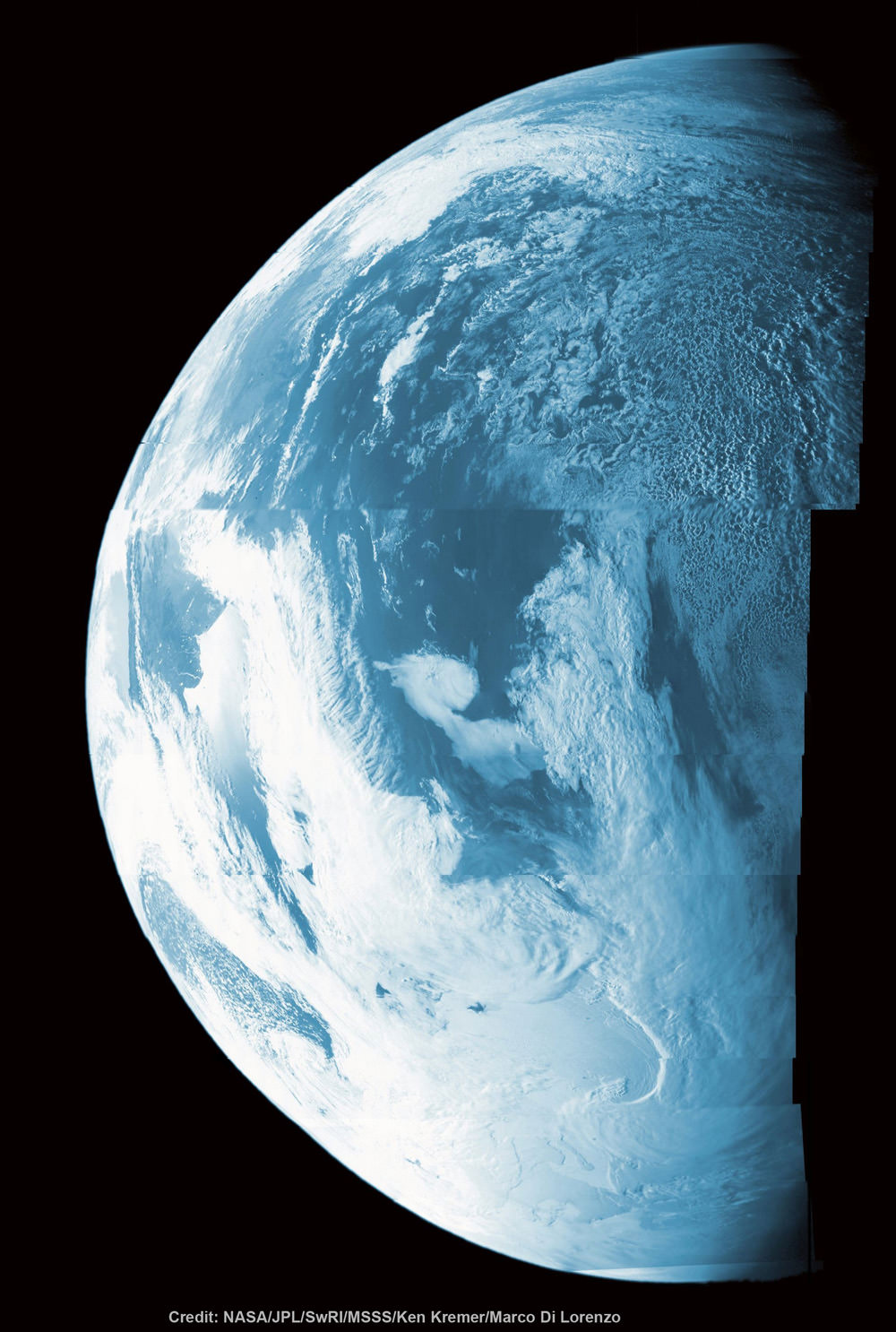

During the Earth flyby, Junocam snapped some striking images of Earth as it sped over Argentina, South America and the South Atlantic Ocean and came within 347 miles (560 kilometers) of the surface.

For example a dazzling portrait of our Home Planet high over the South American coastline and the Atlantic Ocean gives a hint of what’s to come from Jupiter’s cloud tops. See our colorized Junocam mosaic of land, sea and swirling clouds, created by Ken Kremer and Marco Di Lorenzo

Stay tuned here for Ken’s continuing Earth and Planetary science and human spaceflight news.

I’ll go far ‘up a tree and out on a limb’ here and predict that JUNO will find layers of water sorted by pressure and heat into several distinctive variations or types. The layering hundreds to thousands of kilometers thick.

Most extraordinary statistics!

Puts the AWE back in awesome, that’s for sure. Gutta think that the denser elements won’t be too present out that way, but nothing would shock me at this point. The formation of the solar system was violent and anything, even Jupiter could have been moved around. Look at the axis on Uranus. Those moons are really what I want to see. The red spot should prove interesting. The rings, the inner atmosphere, man, these NASA folk got it good. Not that they didn’t work for it. AWEsome!

“We just did the hardest thing NASA’s ever done!”

-really? why so? just curious.

Juno’s trajectory to Jupiter was obviously designed to get it there at practically orbital velocity. Juno was approaching Jupiter at 130,000 mph, yet its speed only needed to be reduced by 1300 mph for it to enter orbit. Would it have been such an engineering challenge to have Juno boosted to a higher speed enroute to Jupiter and give it a larger “fuel tank” to give the engine a longer burn to enter orbit? It would have enabled a shorter trip to Jupiter.

Also, why the use of solar panels? Was this because a nuclear generator would have interfered with Juno’s sensors?

Most of Juno is shielded inside the much-mentioned titanium box, yet its solar panels are fully exposed. What was done to shield the panels from jupiter’s radiation? Is there an anticipated failure rate of the panels over time caused by this radiation?

And why is there such a hostile radiation environment around jupiter? Is jupiter itself emitting this (presumably ionizing) radiation, or is this coming from the Sun?