Being able to witness a solar eclipse is certainly a distinct experience. Even though the spectacle is mostly visual, there can be other effects as well. The air can cool, and observers may notice a decrease in wind speed or a change in wind direction. There might even be an eerie silence.

Experiences like this have been noted for centuries, and famed astronomer Edmund Halley wrote of the ‘Chill and Damp which attended the Darkness’ during an eclipse in 1715, which he noted caused ‘some sense of Horror’ among those who were witnessing the event.

While most people would describe an eclipse as ‘awe-inspiring’ (and not horrifying at all) the atmospheric changes noted by observers over the years has been called the “eclipse wind.” And now, based on the observations of over 4,500 citizen scientists in the UK during the partial eclipse on March 20, 2015, this effect is not just a figment of anyone’s imagination; it is a real phenomenon.

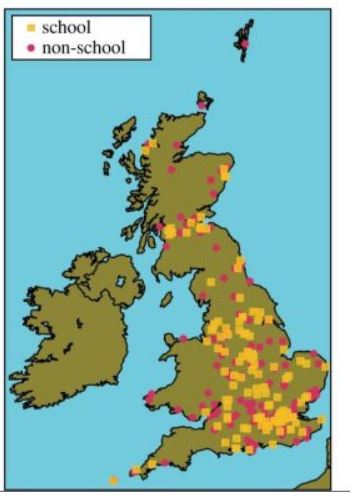

The National Eclipse Weather Experiment (NEWEx) was a UK-wide citizen science project for collecting atmospheric data during that eclipse. Members of the public – including about 200 schools – recorded weather changes such as air temperature, wind speed, wind direction and cloud cover every five minutes during the eclipse. That data, submitted online, was compared with official data from the UK’s Met office observations, the United Kingdom’s national weather service.

“The NEWEx was, as far as we know, a world first, in measuring and analyzing eclipse changes in the weather on a national scale, in close to real time, through engagement of a network of citizen scientists,” wrote researchers Luke Barnard, Giles Harrison, Suzanne Gray and Antonio Portas from the University of Reading, in one of a series of new papers about eclipse meteorology published this week.

The data revealed that not only did the atmosphere cool during the eclipse – which is not surprising since solar radiation is being blocked by the Moon – but the winds and cloud cover also decreased. The cumulative effect is real, not just anecdotal, the team said.

The Data

NEWEx collected 15,606 meteorological observations from 309 locations within the UK and from those observations the science team was able to derive estimates of the near-surface air temperature, cloudiness and near-surface wind speed fields across many UK sites. The data submitted by citizen scientists were combined with Met Office surface weather stations and a network of roadside weather sensors that monitor highway conditions. The combination of data helped unravel the centuries-old mystery of the eclipse wind.

“There have been lots of theories about the eclipse wind over the years, but we think this is the most compelling explanation yet,” said Harrison in a press release from the University of Reading in the UK. “As the sun disappears behind the moon the ground suddenly cools, just like at sunset. This means warm air stops rising from the ground, causing a drop in wind speed and a shift in its direction, as the slowing of the air by the Earth’s surface changes.”

The measurements from citizen scientists clearly showed temperature drops and a decrease in clouds. The team did note that because of the low velocity of winds and some areas where cloud cover change was small, it was difficult for the participants to make some of the measurements. But the high level of participation across the UK provided enough data for the team to make their conclusions.

“Halley also relied on combining eclipse observations from amateur investigators across Britain. We have continued his approach,” Harrison said.

A total of 16 new papers and reports were published this week in a special ‘eclipse meteorology’ issue of the world’s oldest scientific journal, Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A. The special issue is published 301 years after Halley’s report of the eclipse in London in 1715 – and in exactly the same journal.

The team wrote that they hope a similar citizen science effort might take place in August 2017, when a total solar eclipse will be visible from North America, providing another opportunity to study eclipse-induced meteorology changes.

“NEWEx serves as a useful example of the strengths and challenges of using a citizen science approach to study eclipse-induced meteorological changes, and could provide a template for a similar study for the August 2017 eclipse,” the team said.

Sources: Paper: The National Eclipse Weather Experiment: an assessment of citizen scientist weather observations, Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A, University of Reading.

Kudos to CS!