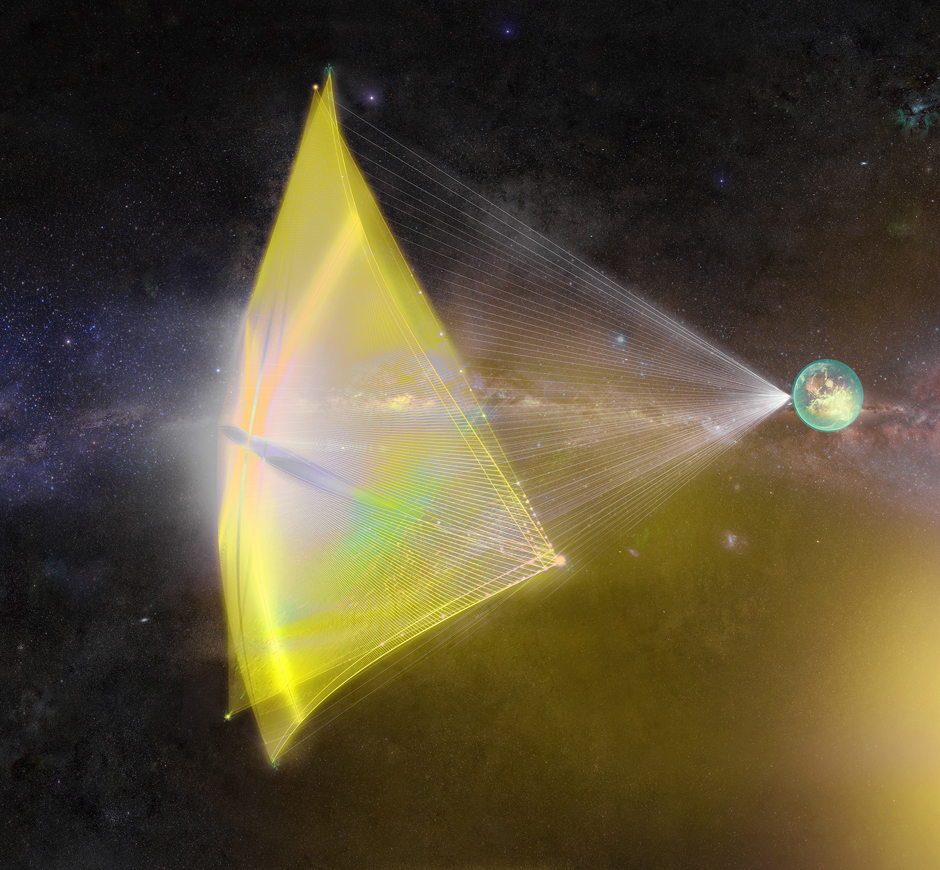

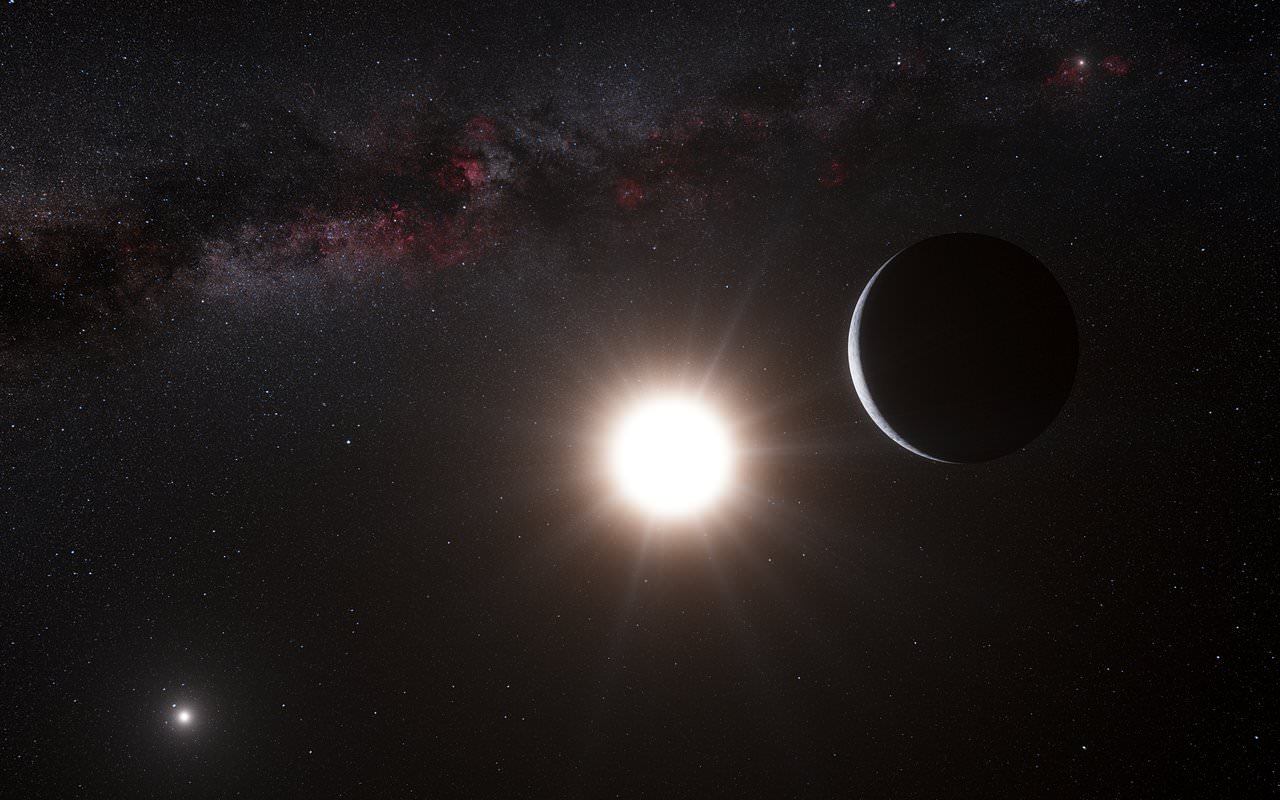

Back in April, Russian billionaire Yuri Milner and famed cosmologist Stephen Hawking unveiled Project Starshot. As the latest venture by Breakthrough Initiatives, Starshot was conceived with the aims of sending a tiny spacecraft to the neighboring star system Alpha Centauri in the coming decades.

Relying on a sail that would be driven up to relativistic speeds by lasers, this craft would theoretically be capable of making the journey is just 20 years. Naturally, this project has attracted its fair share of detractors. While the idea of sending a star ship to another star system in our lifetime is certainly appealing, it presents numerous challenges.

Not one to shy away from any potential problems, Breakthrough Starshot has begun funding the necessary research to make sure that their concept will work. The results of their first research effort appeared recently in arXiv, in a study titled “The interaction of relativistic spacecrafts with the interstellar medium“.

Assessing the risks of interstellar travel, this paper addresses the greatest threat where relativistic speed is concerned: catastrophic collisions! To put it mildly, space is not exactly an empty medium (despite what the name might suggest). In truth, there are a lot of things out there on the “stellar highway” that can cause a fatal crash.

For instance, within interstellar space, there are clouds of dust particles and even stray atoms of gas that are the result of stellar formations and other processes. Any spacecraft traveling at 20% the speed of light (0.2 c) could easily be damaged or destroyed if it suffered a collision with even the tiniest of this particulate matter.

The research team was led by Dr. Chi Thiem Hoang, a postdoctoral fellow at Canadian Institute for Theoretical Astrophysics (CITA) at the University of Toronto. As Dr. Hoang told Universe Today via email:

“To evaluate the risks, we calculated the energy that each interstellar atom or dust grain transfers to the ship along the path of the projectile in the ship. This acquired energy rapidly heats a spot on the ship surface to high temperature, resulting in damage by reducing the material strength, melting or evaporation.”

In short, the danger of a collision comes not from the physical impact, but from the energy that is generated due to the fact that the spaceship is traveling so fast. However, what they found was that while collisions with tiny dust grains are very likely, collisions with heavier atoms that can do the most damage would be more rare.

Nevertheless, the damage from so many tiny collisions will certainly add up over time. And it would only take one collision with a larger particle to end the mission. As Dr. Hoang explained:

“We found that the ship would be damaged by collision with heavy atoms and dust grains in the interstellar medium. Heavy atoms, mostly iron can damage the surface to a depth of 0.1mm. More importantly, the surface of the ship is eroded gradually by dust grains, to a depth of about 1mm. The ship may be completely destroyed if encountering a very big dust grain larger than 15micron, although it is extremely rare.”

In terms of damage, what they determined was that each iron atom can produce a damage track of 5 nanometer across, whereas a typical dust silicate grain measuring just 0.1. micron across (and containing about one billion iron atoms) could produce a large crater on the ship’s surface.

Over time, the cumulative effect of this damage would pose a major risk for the ship’s survival. As a result, Dr. Hoang and his team recommended that some shielding would need to be mounted on the ship, and that it wouldn’t hurt to “clear the road” a little as well.

“We recommended to protect the ship by putting a shield of about 1 mm thickness made of strong, high melting temperature material like graphite.” he said. “We also suggested to destroy interstellar dust by using part of energy from laser sources.”

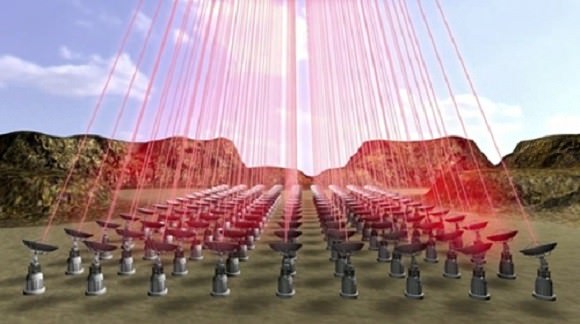

Starshot is the latest in a long line of directed energy concepts that owe their existence to Professor Phillip Lubin. A professor from the University of California, Santa Barbara (UCSB), Lubin is also the mind behind the Directed Energy Propulsion for Interstellar Exploraiton (DEEP-IN) project and the Directed Energy Interstellar Study.

These projects, which are being funded by NASA, seek to harness the technology behind directed-energy propulsion to rapidly send missions to Mars and other locations within the Solar System in the future. Long-term applications include interstellar missions, similar to Starshot.

Other interesting projects overseen by Lubin and the UCSB lab include the Directed Energy System for Targeting of Asteroids and exploRation (DE-STAR). This system calls for the use of lasers to deflect asteroids, comets, and other near-Earth objects (NEO) that pose a credible risk of impact.

In all cases, directed-energy technology is being proposed as the solution to the problems posed by space travel. In the case of Starshot, these include (but are not limited to) inefficiency, mass, and/or the limited speeds of conventional rockets and ion engines.

As Professor Lubin told Universe Today via email, he and his colleagues are in general agreement with the research team and their findings:

“The recent paper by Hoang et al revisits the section (7) in our paper “A Roadmap to Interstellar Flight” that discusses our calculation for the effects of the ISM on the wafer scale spacecraft. Their general conclusion on the effects of the gas and dust collisions were essentially the same as ours, namely that it is an issue, but not a fatal one, if one uses the spacecraft geometry we recommend in our paper, namely orient the spacecraft edge on (like a Frisbee in flight) and then use an edge coating (we use [Beryllium], they use graphite).”

“As for the sail interactions with the ISM we recommend either rotating the sail so it is edge on (lower cross section) or ejecting the sail after the initial few minutes of acceleration as it is no longer needed for acceleration. However. as we desire to use the sail as a reflector for the laser communications we prefer to keep it, though a secondary reflector could be deployed later in the mission if necessary. These detailed questions will be part of the evolving design phase.”

Indeed, there are many safety hazards that have to be accounted for before any mission to interstellar space could be mounted. But as this recent study has shown – with which Professor Lubin agrees – they are not insurmountable, and a mission to Alpha Centauri (or, fingers crossed, Proxima Centauri!) could be performed if the proper precautions are taken.

Who knew the future of space travel would be every bit as cool as we’ve been led to believe – complete with lasers and shielding?

And be sure to enjoy this video from NASA 360, addressing directed-energy propulsion:

Further Reading: arXiv

No one seems to have entertained the possibility of the tiny spacecraft themselves becoming a threat to larger and faster spacecraft sent along the same path as newer technology allows. Imagine the damage imposed by a tiny craft at 20 percent light speed being in the path of a larger craft approaching at 30 or 40 percent light speed?

The odds of actually hitting another spacecraft would be fantastically low.

This is just my opinion. But I think obsession with “going there” is misguided. Light is already coming from everywhere just as fast as it can, safely and for free, but we are still not gathering enough of it! Take the unicorn money and build an array of gigantic VLB space telescopes first! Guaranteed science.

Indeed. I remember reading the Icarus Interstellar project some years ago (a re-analysis of a 1970’s study of a fusion powered flyby probe with a huge 450 ton payload, (in contrast to these 1 gram star chips)). The Icarus team expressed concerns that such a flyby mission would likely be rendered obsolete by advances in remote observation, long before it becomes feasible to build such a craft. If I remember correctly, the team concluded that only a probe that’s capable of entering orbit around its target star and equipped with planetary surface probes would be necessary to complete with future space telescopes, even though such a mission may take 60 years to complete and only feasible to build a hundred years from now. Who knows, maybe telescopes will become advanced enough to even observe herds of critters on a faraway exoplanet by then.

Well, yes, that’s absolutely true. But it’s still not in the nature of humanity to just sit back and look if we can go there. Otherwise we would have never bothered with the Apollo Program. Nor any future plans to land on Mars. Besides, a VLB array may make for some fantastic imaging, but it will never bring me back a medium-rare furry plains critter filet.

In July 1951 the late Prof. Michael Ovenden had a paper ‘Meteors and Space Travel’ in the Journal of the British Interplanetary Society, where he calculated that thin aluminium shielding would be effective up to one-third of lightspeed, with an annealing effect due to heating which would reduce damage. His calculations helped to inspire the ice shield concept of Arthur C. Clarke’s “The Songs of Distant Earth”, revised by Alan Bond for the book-length version. The BIS Project Daedalus study visualised a fairly thick shield of beryllium to protect a vehicle travelling at 12-15% of lightspeed.

Is this a meaningful qualification? “In short, the danger of a collision comes not from the physical impact, but from the energy that is generated due to the fact that the spaceship is traveling so fast.” I think you could say the same about a car crash. The problem is not that the cars come into contact with each other, but the amount of momentum energy exchanged due to their respective velocities.

Well, statistically speaking, very little of the danger from a hydrogen bomb is due to the radiation emitted from the nuclear core before it detonates.

I have to agree, that statement did seem a bit silly.