Ever since the Cassini probe arrived at Saturn in 2004, it has revealed some startling things about the planet’s system of moons. Titan, Saturn’s largest moon, has been a particular source of fascination. Between its methane lakes, hydrocarbon-rich atmosphere, and the presence of a “methane cycle” (similar to Earth’s “water cycle”), there is no shortage of fascinating things happening on this Cronian moon.

As if that wasn’t enough, Titan also experiences seasonal changes. At present, winter is beginning in the southern hemisphere, which is characterized by the presence of a strong vortex in the upper atmosphere above the south pole. This represents a reversal of what the Cassini probe witnessed when it first started observing the moon over a decade ago, when similar things were happening in the northern hemisphere.

These finding were shared at the joint 48th meeting of the American Astronomical Society’s Division for Planetary Sciences and 11th European Planetary Science Congress, which took place from Oct 16th to 21st in Pasadena, California. As the second joint conference between these bodies, the goal of this annual meeting is to strengthen international scientific collaboration in the field of planetary science.

During the course of the meeting, Dr. Athena Coustenis – the Director of Research (1st class) with the National Center for Scientific Research (CNRS) in France – shared the latest atmospheric data retrieved by Cassini. As she stated:

“Cassini’s long mission and frequent visits to Titan have allowed us to observe the pattern of seasonal changes on Titan, in exquisite detail, for the first time. We arrived at the northern mid-winter and have now had the opportunity to monitor Titan’s atmospheric response through two full seasons. Since the equinox, where both hemispheres received equal heating from the Sun, we have seen rapid changes.”

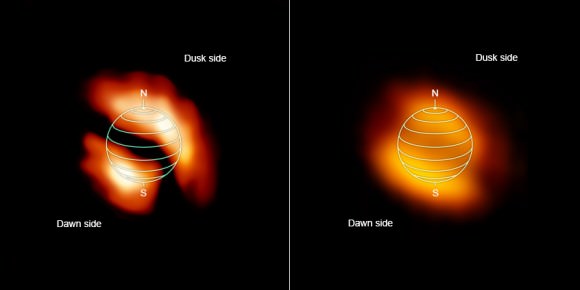

Scientists have been aware of seasonal change on Titan for some time. This is characterized by warm gases rising at the summer pole and cold gases settling down at the winter pole, with heat being circulated through the atmosphere from pole to pole. This cycle experiences periodic reversals as the seasons shift from one hemisphere to the other.

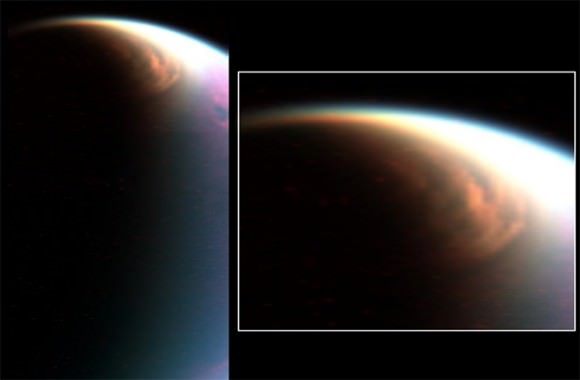

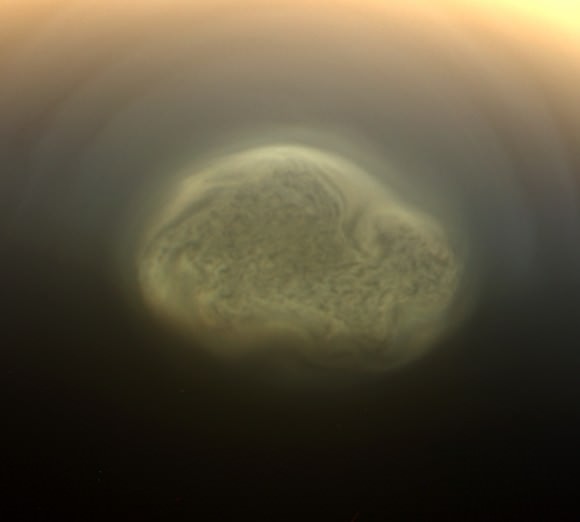

In 2009, Cassini observed a large scale reversal immediately after the equinox of that year. This led to a temperature drop of about 40 °C (104 °F) around the southern polar stratosphere, while the northern hemisphere experienced gradual warming. Within months of the equinox, a trace gas vortex appeared over the south pole that showed glowing patches, while a similar feature disappeared from the north pole.

A reversal like this is significant because it gives astronomers a chance to study Titan’s atmosphere in greater detail. Essentially, the southern polar vortex shows concentrations of trace gases – like complex hydrocarbons, methylacetylne and benzene – which accumulate in the absence of UV light. With winter now upon the southern hemisphere, these gases can be expected to accumulate in abundance.

As Coustenis explained, this is an opportunity for planetary scientists to test out their models for Titan’s atmosphere:

“We’ve had the chance to witness the onset of winter from the beginning and are approaching the peak time for these gas-production processes in the southern hemisphere. We are now looking for new molecules in the atmosphere above Titan’s south polar region that have been predicted by our computer models. Making these detections will help us understand the photochemistry going on.”

Previously, scientists had only been able to observe these gases at high northern latitudes, which persisted well into summer. They were expected to undergo slow photochemical destruction, where exposure to light would break them down depending on their chemical makeup. However, during the past few months, a zone of depleted molecular gas and aerosols has developed at an altitude of between 400 and 500 km across the entire northern hemisphere .

This suggests that, at high altitudes, Titan’s atmosphere has some complex dynamics going on. What these could be is not yet clear, but those who have made the study of Titan’s atmosphere a priority are eager to find out. Between now and the end of Cassini mission (which is slated for Sept. 2017), it is expected that the probe will have provided a complete picture of how Titan’s middle and upper atmospheres behave.

By mission’s end, the Cassini space probe will have conducted more than 100 targeted flybys of Saturn. In so doing, it has effectively witnessed what a full year on Titan looks like, complete with seasonal variability. Not only will this information help us to understand the deeper mysteries of one of the Solar System’s most mysterious moons, it should also come in handy if and when we send astronauts (and maybe even settlers) there someday!

Further Reading: Europlanet