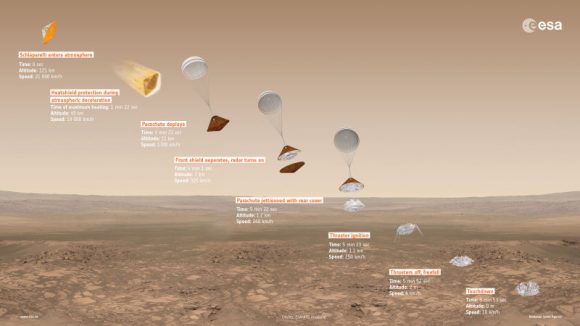

Artist's impression of the ExoMars Schiaparelli lander passing into Mars' atmosphere. Credit: ESA

The European Space Agency (ESA) and Roscomos (the Russian federal space agency) had high hopes for the Schiaparelli lander, which crashed on the surface of Mars on October 19th. As part of the ExoMars program, its purpose was to test the technologies that will be used to deploy a rover to the Red Planet in 2020.

However, investigators are making progress towards determining what went wrong during the lander’s descent. Based on their most recent findings, they concluded that an anomaly took place with an on-board instrument that led to the lander detaching from its parachute and backshell prematurely. This ultimately caused it to land hard and be destroyed.

According to investigators, the data retrieved from the lander indicates that for the most part, Schiaparelli was functioning normally before it crashed. This included the parachute deploying once it had reached an altitude of 12 km and achieved a speed of 1730 km/h. When it reached an altitude of 7.8 km, the lander’s heatshield was released, and it radar altimeter provided accurate data to the lander’s on-board guidance, navigation and control system.

All of this happened according to plan and did not contribute to the fatal crash. However, an anomaly then took place with the Inertial Measurement Unit (IMU), which is there to measure the rotation rates of the vehicle. Apparently, the IMU experienced saturation shortly after the parachute was deployed, causing it to persist for one second longer than required.

This error was then fed to the navigation system, which caused it to generate an estimate altitude that was below Mars’ actual ground level. In essence, the lander thought it was closer to the ground than it actually was. As such, the the parachute and backshell of the Entry and Descent Module (EDM) were jettisoned and the braking thrusters fired prematurely – at an altitude of 3.7 km instead of 1.2 km, as planned.

This briefest of errors caused the lander to free-fall for one second longer than it was supposed to, causing it to land hard and be destroyed. The investigators have confirmed this assessment using multiple computer simulations, all of which indicate that the IMU error was responsible. However, this is still a tentative conclusion that awaits final confirmation from the agency.

As David Parker, the ESA’s Director of Human Spaceflight and Robotic Exploration, said on on Wednesday, Nov. 23rd in a ESA press release:

“This is still a very preliminary conclusion of our technical investigations. The full picture will be provided in early 2017 by the future report of an external independent inquiry board, which is now being set up, as requested by ESA’s Director General, under the chairmanship of ESA’s Inspector General. But we will have learned much from Schiaparelli that will directly contribute to the second ExoMars mission being developed with our international partners for launch in 2020.”

In other words, this accident has not deterred the ESA and Roscosmos from pursuing the next stage in the ExoMars program – which is the deployment of the ExoMars rover in 2020. When it reaches Mars in 2021, the rover will be capable of navigating autonomously across the surface, using a on-board laboratory suite to search for signs of biological life, both past and present.

In the meantime, data retrieved from Schiaparelli’s other instruments is still being analyzed, as well as information from orbiters that observed the lander’s descent. It is hoped that this will shed further light on the accident, as well as salvage something from the mission. The Trace Gas Orbiter is also starting its first series of observations since it made its arrival in orbit on Oct. 19th, and will reach its operational orbit towards the end of 2017.

Further Reading: ESA

Well that’s ruined all my lectures! I’ve spent years talking about space and a go…

According to Darwin, life on Earth may have first appeared in warm little ponds. This…

The habitable zone is where planets could have liquid water on their surfaces, but not…

Air travel produces around 2.5% of all global CO2 emissions, and despite decades of effort…

Researchers study enigmatic asteroid Kamo'oalewa, as China’s first asteroid sample return mission moves toward launch.…

In 2007, astronomers discovered the Cosmic Horseshoe, a gravitationally lensed system of galaxies about five-and-a-half…