Stellar collisions are an amazingly rare thing. According to our best estimates, such events only occur in our galaxy (within globular clusters) once every 10,000 years. It’s only been recently, thanks to ongoing improvements in instrumentation and technology, that astronomers have been able to observe such mergers taking place. As of yet, no one has ever witnessed this phenomena in action – but that may be about to change!

According to study from a team of researchers from Calvin College in Grand Rapids, Michigan, a binary star system that will likely merge and explode in 2022. This is an historic find, since it will allow astronomers to witness a stellar merger and explosion for the first time in history. What’s more, they claim, this explosion will be visible with the naked-eye to observers here on Earth.

The findings were presented last week at the 229th Meeting of the American Astronomical Society (AAS). In a presentation titled “A Precise Prediction of a Stellar Merger and Red Nova Outburst“, Professor Lawrence Molnar and his team shared findings that indicate how this binary pair will merge in about six years time. This event, they claim, will cause an outburst of light so bright that it will become the brightest object in the night sky.

This binary star system, which is known as KIC 9832227, is one that Prof. Molnar and his colleagues – which includes students from the Apache Point Observatory and the University of Wyoming – have been monitoring since 2013. His interest in the star was piqued during a conference in 2013 when Karen Kinemuchi (an astronomers with the Apache Point Observatory) presented findings about brightness changes in the star.

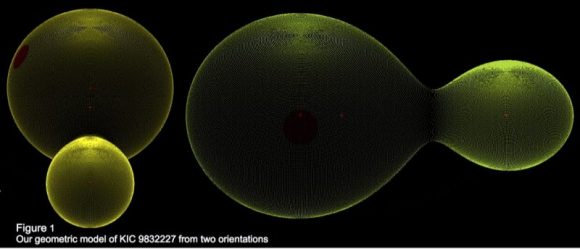

This led to questions about the nature of this star system – specifically, whether it was a pulsar or a binary pair. After conducting their own observations using the Calvin observatory, Prof. Molnar and his colleagues concluded that the star was a contact binary – a class of binary star where the two stars are close enough to share an atmosphere. This brought to mind similar research in the past about another binary star system known as V1309 Scorpii.

This binary pair also had a shared atmosphere; and over time, their orbital period kept decreasing until (in 2008) they unexpectedly collided and exploded. Believing that KIC 9832227 would undergo a similar fate, they began conducting tests to see if the star system was exhibiting the same behavior. The first step was to make spectroscopic observations to see if their observations could be explained by the presence of a companion star.

As Cara Alexander, a Calvin College student and one of the co-authors on the team’s research paper, explained in a college press release:

“We had to rule out the possibility of a third star. That would have been a pedestrian, boring explanation. I was processing data from two telescopes and obtained images that showed a signature of our star and no sign of a third star. Then we knew we were looking at the right thing. It took most of the summer to analyze the data, but it was so exciting. To be a part of this research, I don’t know any other place where I would get an opportunity like that; Calvin is an amazing place.”

The next step was to measure the pair’s orbital period, to see it was in fact getting shorter over time – which would indicate that the stars were moving closer to each other. By 2015, Prof. Molnar and his team determined that the stars would eventually collide, resulting in a kind of stellar explosion known as a “Red Nova”. Initially, they estimated this would take place between 2018 and 2020, but have since placed the date at 2022.

In addition, they predict that the burst of light it will cause will be bright enough to be seen from Earth. The star will be visible as part of the constellation Cygnus, and it appear as an addition star in the familiar Northern Cross star pattern (see above). This is an historic case, since no astronomer has ever been able to accurately predict when and where a stellar collision would take place in the past.

What’s more, this discovery is immensely significant because it represents a break with the traditional discovery process. Not only have small research institutions and universities not been the ones to take the lead on these sorts of discoveries in the past, but student-and-teacher teams have also not been the ones who got to make them. As Molnar explained it:

“Most big scientific projects are done in enormous groups with thousands of people and billions of dollars. This project is just the opposite. It’s been done using a small telescope, with one professor and a few students looking for something that is not likely. Nobody has ever predicted a nova explosion before. Why pay someone to do something that almost certainly won’t succeed? It’s a high-risk proposal. But at Calvin it’s only my risk, and I can use my work on interesting, open-ended questions to bring extra excitement into my classroom. Some projects still have an advantage when you don’t have as much time or money.”

Over the course of the next year, Molnar and his colleagues will be monitoring KIC 9832227 carefully, and in multiple wavelengths. This will be done with the help of the NROA’s Very Large Array (VLA), NASA’s Infrared Telescope Facility at Mauna Kea, and the ESA’s XMM-Newton spacecraft. These observatories will study the star’s radio, infrared and X-ray emissions, respectively.

Molnar also expects that amateur astronomers will be able to monitor the pair’s orbital timing and variations in brightness. And if he and his team’s predictions are correct, every student and stargazer in the northern hemisphere – not to mention people who just happen to be out for a walk – will be privy to the amazing light show. This is sure to be a once-in-a-lifetime event, so stay tuned for more information!

Interestingly enough, this historic discovery is also the subject of a documentary film. Titled “Luminous“, the documentary – which is directed by Sam Smartt, a Calvin professor of communication arts and sciences – chronicles the process that led Prof. Molnar and his team to make this unprecedented discovery. The documentary will also include footage of the Red Nova as it happens in 2022, and is expected to be released sometime in 2023.

Check out the trailer below:

Further Reading: Calvin College, Science Mag

Hi Matt,

Nice article. How bright is this nova supposed to be? The article stated “this explosion will be visible with the naked-eye”. Then just a little later it said “it will become the brightest object in the night sky.” Since there is a lot of difference (to me) between “visible” and “brightest”, did the team give an estimated max. magnitude? Thanks.

Rick

I have to laugh when the word “explosion” is used. Mainstream astrophysicists know only two forces in the current model of cosmology….gravity and explosions. This type of narrow minded thinking is the reason the current standard model is failing on a regular day to day basis. Once the force of electromagnetism assumes it’s proper place as the dominant force in star and galaxy formation then a more correct interpretation of observed data will be published.

Interesting that the binary star system “*that will likely merge and explode in 2022*” is about 1800 light-years away… so what we’ll see in 2020 is a flash of light emitted about 1800 years ago when (if?) the binary stars merged.

Yes, the effects of the explosion will be apparent to us in 2022. The effects of relativity are implied here, friend.

I’m wondering about the environment around KIC 9832227 both close in and in the area. Being the biggest “local” flash since V1309 Scorpii brings up it’s current recognition as a great source to explore light echoes off clouds of dust. I hope that lots of creative ideas come along exploring this. Another website mentioned there is a third part to the KIC system but not responsible for the periodicity so it’s worth characterizing too and even watch for a change in its orbital period as the explosion ejects mass beyond its orbit plus collision issues. Plus maybe it would be a chance to see planets…

Here’s a detailed map of the constellation. Hopefully the Gaia program can have some details in this direction. You can get a general idea of the area arrowing out the picture at http://simbad.u-strasbg.fr/simbad/sim-id?Ident=%406099320&Name=KIC%209832227&submit=submit and then zooming out.

And If I’m reading the Gaia interface right it is source_id=2128318232616057856.