Saturn's largest Moon, Titan, is the only other world in our Solar System that has stable liquid on its surface. That alone, and the fact that the liquid is composed of methane, ethane, and nitrogen, makes it an object of fascination. The bright spot features that

Cassini

observed in the methane seas that dot the polar regions only deepen the fascination.

A

new paper

published in

Nature Astronomy

digs deeper into a phenomenon in Titan's seas that has been puzzling scientists. In 2013, Cassini noticed a feature that wasn't there on previous fly-bys of the same region. In subsequent images, the feature had disappeared again. What could it be?

One explanation is that the feature could be a

disappearing island

, rising and falling in the liquid. This idea took hold, but was only an initial guess. Adding to the mystery was the doubling in size of these potential islands. Others speculated that they could be waves, the first waves observed anywhere other than on Earth. Binding all of these together was the idea that the appearance and disappearance could be caused by seasonal changes on the moon.

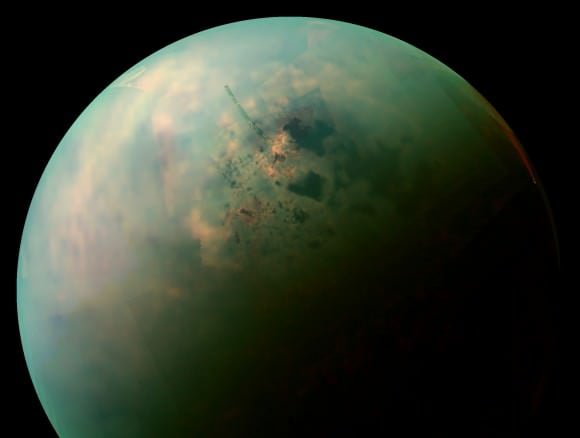

[caption id="attachment_128226" align="alignnone" width="580"]

Titan's dense, hydrocarbon rich atmosphere remains a focal point of scientific research. Credit: NASA[/caption]

Now, scientists at NASA's

Jet Propulsion Laboratory

(JPL) think they know what's behind these so-called 'disappearing islands,' and it seems like they are related to seasonal changes.

The study was led by Michael Malaska of JPL. The researchers simulated the frigid conditions on Titan, where the temperature is -179.2 Celsius. At that temperature, some interesting things happen to the nitrogen in Titan's atmosphere.

On Titan, it rains. But the rain is composed of extremely cold methane. As that methane falls to the surface, it absorbs significant amounts of nitrogen from the atmosphere. The rain hits Titan's surface and collects in the lakes on the moon's polar regions.

The researchers manipulated the conditions in their experiments to mirror the changes that occur on Titan. They changed the temperature, the pressure, and the methane/ethane composition. As they did so, they found that nitrogen bubbled out of solution.

"Our experiments showed that when methane-rich liquids mix with ethane-rich ones -- for example from a heavy rain, or when runoff from a methane river mixes into an ethane-rich lake -- the nitrogen is less able to stay in solution," said Michael Malaska of JPL. This release of nitrogen is called exsolution. It can occur when the seasons change on Titan, and the seas of methane and ethane experience a slight warming.

"Thanks to this work on nitrogen's solubility, we're now confident that bubbles could indeed form in the seas, and in fact may be more abundant than we'd expected," said Jason Hofgartner of JPL, a co-author of the study who also works on Cassini's radar team. These nitrogen bubbles would be very reflective, which explains why Cassini was able to see them.

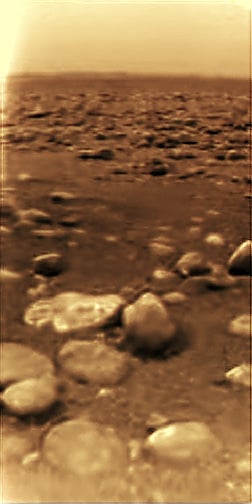

[caption id="attachment_132267" align="alignnone" width="252"]

The first-ever images of the surface of a new moon or planet are always exciting. The Huygens probe was launched from Cassini to the surface of Titan, but was not able investigate the lakes and seas on the surface. Image Credit: ESA/NASA/JPL/University of Arizona[/caption]

The seas on Titan may be what's called a prebiotic environment, where chemical conditions are hospitable to the appearance of life. Some think that the seas may already be home to life, though there's no evidence of this, and Cassini wasn't equipped to investigate that premise. Some

experiments

have shown that an atmosphere like Titan's could generate complex molecules, and even the building blocks of life.

NASA and others have talked about different ways to explore Titan, including balloons, a drone,

splashdown landers

, and even a submarine. The

submarine idea

even received a NASA grant in 2015, to develop the idea further.

So, mystery solved, probably. Titan's bright spots are neither islands nor waves, but bubbles.

Cassini's mission will end soon, and it'll be quite some time before Titan can be investigated further. The question of whether Titan's seas are hospitable to the formation of life, or whether there may already be life there, will have to wait. What role the nitrogen bubbles play in Titan's life question will also have to wait.

Universe Today

Universe Today