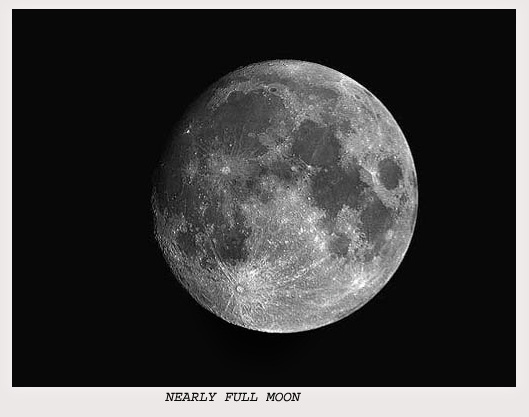

It’s big. It’s bright. It’s the Moon! Even though the dark skies will be trashed thanks to the influence of this weekend’s Moon, there’s still a lot of astronomy we can practice together. Grab your telescopes or binoculars and let’s head out, because… Here’s what’s up!

Friday, April 18 – Tonight, if you’re looking at the Moon near the southern cusp you’ll spy two outstanding features. The easiest is crater Schickard – a class V mountain-walled plain spanning 227 kilometers. Named for German astronomer Wilhelm Schickard, this beautiful old crater with subtle interior details has another crater caught on its northern wall which is named Lehmann. But, look further south for one of the Moon’s most incredible features – Wargentin. Among the many strange things on the lunar surface, Wargentin is unique. Once upon a time, it was a very normal crater and had been so for hundreds of millions of years, then it happened: either a fissure opened in its interior, or the meteoric impact which formed it caused molten lava to begin to rise. Oddly enough, Wargentin’s walls did not have large enough breaks to allow the lava to escape, and it continued to fill the crater to the rim. Often referred to as “the Cheese,” enjoy Wargentin tonight for its unusual appearance…and be sure to note Nasmyth and Phocylides as well.

Saturday, April 19 – Despite the Moon’s overpowering light, you may have noticed brilliant blue-white Spica very near the Moon tonight. Take the time to look at this glorious helium star, which shines 2300 times brighter than the Sun which lights tonight’s Moon. Roughly 275 light-years away, Alpha Virginis is a spectroscopic binary. The secondary star is about half the size of the primary and orbits it about every four days from its position of about 18 million kilometers from center to center… That’s less than one-third the distance at which Mercury orbits the Sun (here are some planet Mercury facts). The two stars can actually graze during an eclipse. Oddly enough, Spica is also a pulsating variable and the very closeness of this pair make for fine viewing – even without a telescope!

While we’re out, have a look at R Hydrae about a fingerwidth east of Gamma – which is itself a little more than fistwidth south of Spica. R Hydrae (RA 13 29 42 Dec -23 16 52) is a beautiful, red, long-term variable first observed by Hevelius in 1662. Located about 325 light-years from us, it’s approaching – but not so very fast. Be sure to look for a visual companion star as well.

Sunday, April 20 – Tonight’s Full Moon is often referred to as the “Pink Moon” of April. As strange as the name may sound, it actually comes from the herb moss pink or wild ground phlox. April is the time of blossoming and the “pink” is one of the earliest widespread flowers of the spring season. As always, it is known by other names as well, such as the Full Sprouting Grass Moon, the Egg Moon, and the coastal tribes referred to it as the Full Fish Moon. Why? Because spring was the season the fish swam upstream to spawn.

While skies are bright, let’s take this opportunity to have a look at Alpha Canis Minoris, now heading west. If you’re unsure of which bright star is, you’ll find it in the center of the diamond shape grouping in the southwest area of the early evening sky in the northern hemisphere. Known to the ancients as Procyon, “The Little Dog Star,” it’s the eighth brightest star in the night sky and the fifth nearest to our solar system. For over 100 years astronomers have known this brilliant star was not alone – it had a companion, and a very unusual one. 15,000 times fainter than the parent star, Procyon B is an example of a white dwarf whose diameter is only about twice that of Earth. But its density exceeds two tons per cubic inch! (Or, a third of a metric ton per cubic centimeter.) While only very large telescopes can resolve this second closest of the white dwarf stars, even the moonlight can’t dim its beauty.

2 tons per square inch? Sorry to be picky but I’m sure you’ll fix it asap.

“Oddly enough, Spica is also a pulsating variable […]”

It’s not “odd” at all, given your own description of Spica, with a companion so close that “the two stars can actually graze during an eclipse.”

Done. “per square inch” now reads “per cubic inch” – the correct terminology.

As for odd? I’m sorry. Eclipsing binaries are one thing… But to have an eclipsing spectroscopic binary whose primary star is also a pulsating variable is just a little off the norm.

But I welcome comments as to why it isn’t! 😉

Tammy,

Thanks for publishing “What’s Up” again, even in a weekend edition. I suppose most of us are able to observe during the weekend. And yes, the Nearly Full Moon was stunning on Friday night – blinding even with a grey filter. (I took my telescopes to a Girl Scout Camp over the weekend and was able to wow a few people with the Moon and Saturn…) We had bad weather here on Saturday night. I hope to see more of “What’s Up!” Thanks!