Thanks to the

Cassini mission

, we have learned some truly amazing things about Saturn and its largest moon,

Titan

. This includes information on its dense atmosphere, its geological features, its methane lakes, methane cycle, and organic chemistry. And even though

Cassini

recently ended its mission by

crashing into Saturn's atmosphere

, scientists are still pouring over all of the data it obtained during its 13 years in the Saturn system.

And now, using Cassini data, two teams led by researchers from Cornell University have released two new studies that reveal even more interesting things about Titan. In one, the team created a complete

topographic map

of Titan using

Cassini's

entire data set. In the second, the team revealed that

Titan's seas have a common elevation

, much like how we have a "sea level" here on Earth.

The two studies recently appeared in the

Geophysical Research Letters,

titled "

Titan's Topography and Shape at the End of the Cassini Mission

" and "

Topographic Constraints on the Evolution and Connectivity of Titan's Lacustrine Basins

". The studies were led by Professor Paul Corlies and Assistant Professor Alex Hayes of Cornell University, respectively, and included members from

The Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory

, NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, the

US Geological Survey

(USGS), Stanford University, and the

Sapienza Universita di Roma

.

[caption id="attachment_138130" align="aligncenter" width="535"]

This true-color image of Titan, taken by the Cassini spacecraft, shows the moon's thick, hazy atmosphere. Credit: NASA

[/caption]

In the first paper, the authors described how topographic data from multiple sources was combined to create a global map of Titan. Since only about 9% of Titan was observed with high-resolution topography (and 25-30% in lower resolution) the remainder of the moon was mapped with an interpolation algorithm. Combined with a global minimization process, this reduced errors that would arise from such things as spacecraft location.

The map revealed new features on Titan, as well as a global view of the highs and lows of the moon's topography. For instance, the maps showed several new mountains which reach a maximum elevation of 700 meters (about 3000 ft). Using the map, scientists were also able to confirm that two locations in the equatorial regions are depressions that could be the result of ancient seas that have since dried up or cryovolcanic flows.

The map also suggests that Titan may be more oblate than previously thought, which could mean that the crust varies in thickness. The data set is available online, and the map which the team created from it is already proving its worth to the scientific community. As Professor Corlies explained in a Cornell

press release

:

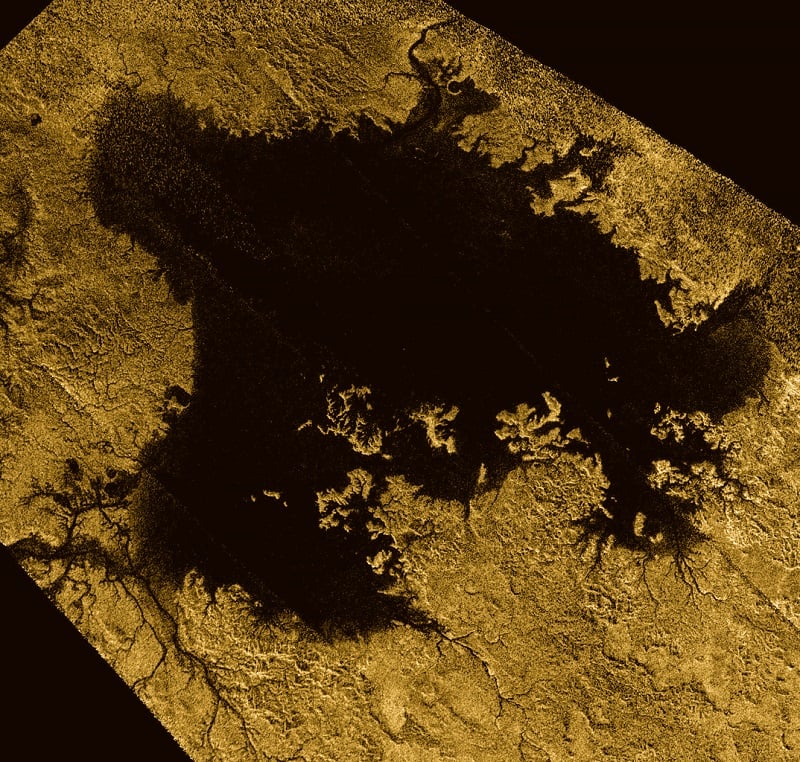

[caption id="attachment_137513" align="aligncenter" width="580"]

False-color mosaic of Titan's northern lakes, made from infrared data collected by NASA's Cassini spacecraft. Credit: NASA

[/caption]

Looking ahead, this map will play an important role when it comes tr scientists seeking to model Titan's climate, study its shape and gravity, and its surface morphology. In addition, it will be especially helpful for those looking to test interior models of Titan, which is fundamental to determining if the moon could harbor life. Much like Europa and Enceladus, it is believed that Titan has a liquid water ocean and hydrothermal vents at its core-mantle boundary.

The second study, which also employed the new topographical map, was based on Cassini radar data that was obtained up to just a few months before the spacecraft burned up in Saturn's atmosphere. Using this data, Assistant Professor Hayes and his team determined that Titan's seas follow a constant elevation relative to Titan's gravitational pull. Basically, they found that Titan has a sea level, much like Earth. As Hayes

explained

:

This common elevation is important because liquid bodies on Titan appear to be connected by something resembling an aquifer system. Much like how water flows underground through porous rock and gravel on Earth, hydrocarbons do the same thing under Titan's icy surface. This ensures that there is transference between large bodies of water, and that they share a common sea level.

[caption id="attachment_137194" align="aligncenter" width="580"]

Artist concept of Cassini's last moments at Saturn. Credit: NASA/JPL.

[/caption]

"We don't see any empty lakes that are below the local filled lakes because, if they did go below that level, they would be filled themselves," said Hayes. "This suggests that there's flow in the subsurface and that they are communicating with each other. It's also telling us that there is liquid hydrocarbon stored on the subsurface of Titan."

Meanwhile, smaller lakes on Titan appear at elevations several hundred meters above Titan's sea level. This is not dissimilar to what happens on Earth, where large lakes are often found at higher elevations. These are known as "Alpine Lakes", and some well-known examples include Lake Titicaca in the Andes, Lakes Geneva in the Alps, and Paradise Lake in the Rockies.

Last, but not least, the study also revealed the vast majority of Titan's lakes are found within sharp-edged depressions that are surrounded by high ridges, some of which are hundreds of meters high. Here too, there is a resemblance to features on Earth - such as the Florida Everglades - where underlying material dissolves and causes the surface to collapse, forming holes in the ground.

The shape of these lakes indicate that they may be expanding at a constant rate, a process known as uniform scarp retreat. In fact, the largest lake in the south - Ontario Lacus - resembles a series of smaller empty lakes that have coalesced to form a single feature. This process is apparently due to seasonal change, where autumn in the southern hemisphere leads to more evaporation.

While the C

assini

mission is no longer exploring the Saturn system, the data it accumulated during its multi-year mission is still bearing fruit. Between these latest studies, and the many more that will follow, scientists are likely to reveal a great deal more about this mysterious moon and the forces that shape it!

Further Reading: NASA, Cornell University

,

*Geophysical Research Letters*

Universe Today

Universe Today